Philosophy. Oral Rhetoric. Christian Formation. Business. Biology.

These are among the many subjects studied by incarcerated college students. Behind barbed wire, concrete walls, and steel doors resides intellectually curious men and women who are enrolled in rigorous academic programs. But the resources for postsecondary education are sparse. And few Christians are assisting in this academic space.

In the early 2000s and for many years I engaged in juvenile justice advocacy work, prison ministry, and grassroots efforts to end mass incarceration—before it was popular, sensical, or sexy. Before Michelle Alexander wrote the seminal book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarcerations in the Age of Colorblindness,1 indicting America for a systematic and discrimination-fueled incarceration explosion. Before Bryan Stevenson and Just Mercy2 were household names. I was an urban Christian leader and college educator trying to figure out how my faith would come to bear on this social justice issue—the one few were talking about—the exponential growth of America’s prison population from the 1980s (300,000) to the early 2000s (over 2 million). Fast forward to 2015. I took a year-long sabbatical from Eastern University to research how Christian institutions of higher learning could address the issue of mass incarceration in America.

Historical Context

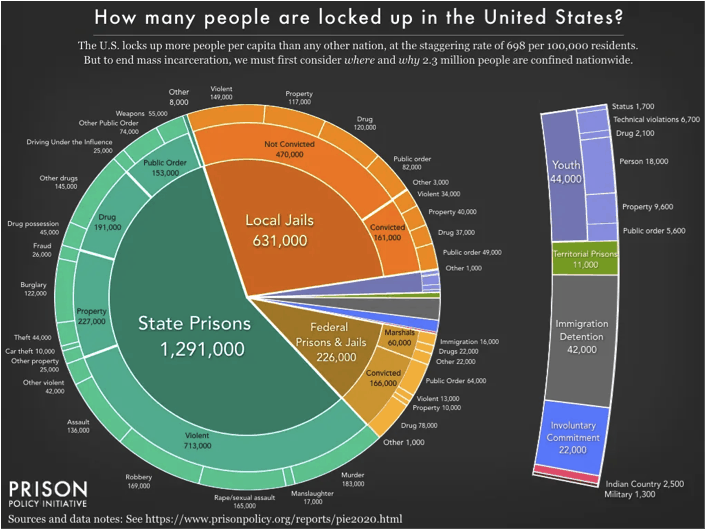

The United States is the world’s leading jailer, incarcerating more of its citizens than any other country in the world. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, 2.3 million Americans are behind bars in federal, state, local, juvenile detention, and immigration detention facilities, and another 4.7 million are under corrections control through probation and parole.3 Approximately 1 in 3 Americans have a criminal record—some of whom don’t realize it. Our systems of justice are biased against the poor and people of color, and families and distressed communities (urban and rural) are collateral damage. People with prison records, including the many who are arrested, tried, and/or sentenced unjustly, are stereotyped, marginalized, discriminated against, and disenfranchised upon release—and many end up back in prison. Prison Bible studies—I mean prison education—makes a difference.

The Value of Prison Education

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 95% of people in state prisons one day come home.4 And jails have transient populations as persons are typically housed for under two years. Returning residents must rebuild their lives while facing the challenges of family reunification, community reintegration, securing housing, employment, and medical care, and sometimes addiction services. Reentry is difficult. Preparation for reentry must begin while people are still in prison so that people are released with the necessary knowledge, skills, and resources.

Academic and policy research has shown that educational programs—including Adult Basic Education (ABE), GED education, life skills, vocational training, and postsecondary education—all help to create better environments within correctional institutions and reduce recidivism after release.5 With higher levels of educational attainment, recidivism rates conversely decrease. According RAND Corporation’s 2013 Report, Evaluating the Effectiveness of Corrections Education, people in prison who participated in structured education while incarcerated were at least 43% less likely to recidivate than those who did not.6 Research shows that prison education also:

- is personally transformative

- inspires the children of incarcerated parents to value education

- increases likelihood for employment upon release, and

- creates better conditions and reduces violence inside correctional facilities.

According to the Institute for Higher Education Policy (2011), Postsecondary Correctional Education (PSCE) has emerged as a cost saving form of rehabilitation, reentry preparation, and recidivism reduction.

According to Lucius Couloute, Policy Analyst with the Prison Policy Initiative, people who have been incarcerated are “often relegated to the lowest rungs of the educational ladder…and after release rarely get the chance to make up for the educational opportunities from which they’ve been excluded.”7 As the graphs below depict, less than 5% of formerly incarcerated people have earned a college degree compared to 34% of the general public, they are twice as likely to have no high school credential at all, and of the 33% that have GED’s as their highest degree, 73% received them while in lock up.8 The prison context presents a new opportunity for people to earn academic credentials that they were unable to receive on the outside.

Over the last decade, there has been a national movement to provide resources and supports for correctional educational initiatives because the benefit to individuals and society at large is great. Bi-partisan legislative support has emerged. State and local departments of corrections, approximately 85%, have budgeted for and welcomed institutions with educational offerings. Nonprofit organizations such as Petey Greene have come alongside with academic support services. Innovative models of postsecondary education such as the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program have created opportunities for traditional college students to take classes alongside inside students at correctional facilities, and they have trained thousands of teachers. But the Church, for the most part, has occupied its familiar corrections space, offering ubiquitous worship services and Bible studies. These are important—of course. But more is needed from the Church.

Over the last decade, there has been a national movement to provide resources and supports for correctional educational initiatives because the benefit to individuals and society at large is great. Bi-partisan legislative support has emerged. State and local departments of corrections, approximately 85%, have budgeted for and welcomed institutions with educational offerings. Nonprofit organizations such as Petey Greene have come alongside with academic support services. Innovative models of postsecondary education such as the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program have created opportunities for traditional college students to take classes alongside inside students at correctional facilities, and they have trained thousands of teachers. But the Church, for the most part, has occupied its familiar corrections space, offering ubiquitous worship services and Bible studies. These are important—of course. But more is needed from the Church.

The Church and Prison Education

Preaching and teaching the Bible is my ministry comfort zone. To do this behind bars for a population I love was not a difficult transition. Over the years I noticed, but ignored the fact, that volunteers from various churches would come and offer similar services. It was not uncommon to see persons from different religious organizations waiting to enter the facility at the same time. Gatherings were usually well attended. Later I discovered that the imprisoned attended diverse faith assemblies, frequently, in order to escape being on the cell blocks. How did I miss that? And how did I miss that so many other needs were not being met? Has the Christian community missed the mark by taking a missiological approach to prison work that focuses on evangelism and discipleship rather than developing a more contextualized ministry plan based on an assessment of needs and an understanding of holistic outreach?

The Church, for the most part, has occupied its familiar corrections space, offering ubiquitous worship services and Bible studies. These are important—of course. But more is needed from the Church.

In 2018 I interviewed the Director of Chaplaincy Services, Restorative and Transitional Services for the Philadelphia Prison System. He also oversees other chaplains representing multiple faiths. While he applauded the efforts of all religious organizations who come into the facilities, he noted that churches who visited the facilities typically halted their work at preaching and teaching. He noted that those imprisoned need other helps to ensure successful reentry. And when they are released, they need the faith community to show up, literally, because some have nowhere to go. It is time for the Christian community to rethink how to best leverage its human resources so as to work for true transformation in the lives of the incarcerated and of the system that incarcerated them at exponential rates.

In the book Rethinking Incarceration, Dominique Gilliard describes a 2016 survey of mainline and evangelical pastors, indicating that “only one out of five claimed involvement in (criminal justice) advocacy efforts. Among this number, African American pastors are more than two times more likely to be actively involved in reform, advocacy, or activist work regarding the criminal justice system.”9 Christian colleges and universities, however, are finding a way into this space.

For Christian communities whose hearts have hardened to this population, it is time for self critique.

Expanding the scope of Christian ministry in prison is rooted in the biblical concepts of shalom (everyone has the right to flourish, Jer. 29:7), imago Dei (every one bears God’s image and has inherent worth), and liberation (everyone has the right to freedom from oppression, forgiveness, and second chances, Luke 4:17-19). This work is motivated by the biblical principles of love and empathy for the imprisoned (Matthew 25:34-40; Hebrews 13:3). Jesus’ model of ministry demonstrated God’s disposition to those on the margins of society. A community’s outcasts, the marginalized and forgotten, and even those with criminal behavior were the objects of Jesus’ concern and recipients of his mercy. If we follow his example, we should run to those others have cast away—including those with criminal convictions. Both the Old and New Testaments chronicle God’s redemption and empowerment of those with criminal behaviors. Consider Moses (guilty of murder), David (guilty of conspiracy to commit murder, sexual assault), and Peter (guilty of assault with a deadly weapon). Even Jesus himself was a convicted criminal who died as a result of capital punishment. For Christian communities whose hearts have hardened to this population, it is time for self critique.

Because of the vast research on the personal and societal implications of quality correctional educational experiences and the unique ability to integrate academics with the Christian faith, Christian higher education institutions have begun serving inside jails and prisons. For example, according to its core commitments Eastern University seeks to work with and for the poor, oppressed, and suffering persons as part of its Christian discipleship. Its program in a nearby prison is an outgrowth of that. The academy is operating in this space with little assistance from the Church at large.

In the late 1960s federal dollars were allocated for college students in prison. By 1982 there were 350 higher education institutions offering credit bearing courses behind bars, enrolling 27,000 students. According to Wendy Sawyer, Prison Policy Initiative Research Director, “By the early 1990s, it is estimated that 772 programs were operating in 1,287 correctional facilities across the nation.”10 That number drastically reduced to 11 when, as part of the 1994 Violent Crime Control Act and Law Enforcement Act, federal aid, including Pell grants and student loans, was banned for those in state and federal correctional institutions. The incarcerated were and are overwhelmingly poor and relied heavily on federal aid programs. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Education instituted Second Chance Pell (SCP) on an experimental basis for a limited number of schools. Some of the 65 schools selected to participate in SCP were members of the Council for Christian Colleges and Universities (CCCU). In May 2020, Eastern University and at least two other CCCU schools were selected to participate in the SCP experimental site initiative.

In 2017 the CCCU, under the leadership of President Shirley V. Hoogstra, partnered with Prison Fellowship which is a leader in justice reform and proponent of “unlocking brighter futures for people with a criminal record.” They have worked together in an effort to increase awareness regarding reintegration barriers. Prison Fellowship declared April 2017 as the first ever Second Chance Month, and in 2018 the President and the U.S. Senate officially recognized April as Second Chance Month, along with 19 state and local governments and more than 230 partner organizations.11 The CCCU and Prison Fellowship have also advocated for incarcerated students in postsecondary programs to be eligible to receive federal financial aid (currently banned with few exceptions). In 2019, the CCCU established a Prison Education Task Force comprised of the prison education program directors of Calvin University and Calvin Theological Seminary (offering education at Handlon Correctional Facility), Campbell University (offering education at Sampson Correctional Institution), Eastern University (offering education at State Correctional Institution Chester), Lipscomb University (offering educational opportunities at Tennessee Prison for Women), and Wheaton College (offering training to prison volunteers).

A View of Christian Community Collaboration

The Eastern University Prison Education Program (PEP) provides transformational education for those incarcerated and returning from lock up. PEP’s overall goal is to reduce mass incarceration and assist in the rehabilitative process of incarcerated individuals by offering high quality educational experiences and respected credentials. It operates inside State Correctional Institution Chester, a medium security prison for men. Based on a survey of the residents, this new program began with non-credit bearing courses assisting residents in personal development and reentry preparation.

A 25-person advisory team assists Eastern’s PEP. This team is comprised of academics, university staff, community stakeholders, and formerly incarcerated persons. One of our lead advisors, John Pace, is the Juvenile Life Without Parole Reentry Coordinator for the Youth Sentencing and Reentry Project in Philadelphia. He is also a former juvenile lifer having spent 31 years in prison, beginning at the age of 17. While in confinement, he earned a paralegal certificate, as well as an Associates degree and Bachelor’s degree from Villanova University, a catholic school. The voices of those directly impacted by mass incarceration, whether they be Christian or not, are key collaborators.

Nyack College has one of the largest and most successful college in prison programs, having provided services in the Fishkill Correctional Facility with a 0% recidivism rate among its graduates (as of January 2020). Its ability to connect through other networks—Hudson Link, faith communities—have contributed to its success. Nyack alumnus, Sean Pica, who earned his degree at Sing Sing prison, is now Executive Director of Hudson Link and a founding board member of the Alliance for Higher Education in Prison.

Monetary contributions are critical to the success of higher education in prison programs, particularly if for-credit courses are offered. Even at deeply discounted tuition rates, this population typically makes less than $.50/hour while incarcerated and are unable to avoid the costs of tuition and books. Churches could budget, fundraise, or collect offerings to invest in these students. After all, they are all likely returning to our communities. When I visited prospective students at Eastern’s partner facility for the first time, I was overwhelmed by the packed room of men who were highly motivated to improve their lives by continuing their education. They were even willing to help fundraise to assist any men who could not pay for credit bearing courses.

Vast experience, expertise, networks, and skills exist within congregations. Members have more to offer than Bible lessons and prayers. In fact, when partnering with Christian higher educational institutions, it is easier to integrate one’s faith into service. Church members may serve as academic tutors, guest instructors, administrative support, supportive reentry communities, and reentry employers. Para-church organizations, nonprofits, and Christian-owned businesses may come along and do the same. Everence, for example, a Christian financial services organization affiliated with the Mennonite Church USA, partnered with Eastern University to offer a Financial Wellness course at the prison. The students worked hard completing tasks in between classes. And they loved the class! The waiting list of persons to take this course, and to participate in other offerings, is extensive.

There are many ways for the Church to move incarnationally into correctional facility spaces. Supporting the incarcerated through educational initiatives is strategic, and it is needed. David Garlock, Eastern University alum featured in the movie “Just Mercy”,12 testifies to the tremendous impact of correspondence classes during his incarceration in Alabama. “Education changed my trajectory,” he said. He also shares that God, working through a supportive church community during his imprisonment and upon his release, and a welcoming and supportive Christian university were instrumental to his success. He is now a successful returning resident, reentry professional, a criminal justice reform advocate, and a prison education advisory councilperson. The Church and academy can work with and for incarcerated persons, so that they return to communities better able to contribute, flourish, and thrive.

Notes

1 Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarcerations in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010).

2 Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy (New York: Random House, 2014).

3 Wendy Sawyer, “Since You Asked: How did the 1994 crime bill affect prison college programs?” Prison Policy Initiative August 22, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2019/08/22/college-in-prison/.

4 Bureau of Justice Statistics, April 2019. https://www.bjs.gov/content/reentry/reentry.cfm.

5 W. Erisman and J. Contardo, “Learning to Reduce Recidivism: A 50-State Analysis of Postsecondary Correctional Education Policy,” Institute for Higher Education Policy, 2005. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED558210.

6 RAND Corporation Report. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR266.html.

7 L. Couloute, Getting Back on Course: Educational exclusion and attainment among formerly incarcerated people. Prison Policy Institute, October 2018.

8 Ibid.

9 D. Gilliard. Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for Justice That Restores, (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2018) p. 111. See book review elsewhere in this issue: https://jofum.com/review-rethinking-incarceration-advocating-for-justice-that-restores.

10 Sawyer, op. cit.

11 Retrieved from www.prisonfellowship.org.

12 Reviewed elsewhere in this issue: https://jofum.com/reviews/review-just-mercy-film.

For Further Reading

Aalai, A. (April 11, 2014). “Access to education for prisoners’ key to reform.” Psychology Today. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-first-impression/201404/access-education-prisoners-key-reform.

Boldin, A. (June 2018). “Second chance pell experimental sites initiative update.” Vera Institute of Justice. Retrieved from: https://www.vera.org/publications/second-chance-pell-experimental-sites-initiative-update.

Bozick, R. (August 2013). “Does providing inmates with education improve post release outcomes?: A meta-analysis of correctional education programs in the United States.” (Originally published in Journal of Experimental Criminology).

Daniel K. (2017). College in Prison: Reading in an age of mass incarceration. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Gilliard, D. (2018). Rethinking Incarceration: Advocating for justice that restores.Downers Grove, IL: IVP Books.

Goode, W. W., Lewis, C. Trulear, H.D. (2011). Ministry with Prisoners and Families: a way forward. King of Prussia, PA: Judson Press.

Hall, S. T. “A Working Theology of Prison Ministry.” The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 58 no 3 Fall 2004, p 169-178.

King Jr., J. B. (July 26, 2016). “U.S. Secretary of Education: Let’s educate, not incarcerate.” Education Week. Retrieved from: http://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2016/07/26/us-secretary-of-education-lets-educate-not.html?qs=educating+inmates.

Lageman, E.C. (2017). Liberating Minds: The case for college in prison. New Press.

Michaels, B. (2011). College in Prison. Bloomington, IN: Trafford Publishing.

Morgan, L. (August 22, 2016). “Adding criminal justice reform to prison ministry,” Christianity Today. www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2016/september/criminal-justice-reform-prison-ministry.html.

Perry, J. (2016). God Behind Bars. Thomas Nelson Inc.

PrisonEducation.com. (2012). “A brief history of prisons and prison education.” Retrieved from: https://prisoneducation.com/prison-education-news/2012/12/13/a-brief-history-of-prisons-and-prison-education.html.

Sawyer, W. (March 24, 2020). “Mass incarceration: the whole pie 2020”. Retrieved from: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2020.html?c=pie&gclid=EAIaIQobChMI3561iNT36AIVCp6fCh2B0AwAEAAYASAAEgLxHfD_BwE

Shopshire, J. M. ed. (2008). I was in prison: United Methodist perspectives on prison ministry. United Methodist General Board of Higher Education.

Vorster, N. (2011). Created in the image of God: Understanding God’s relationship with humanity. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications.

Zoukis, C. (2014). College for convicts: The case for higher education in prisons. McFarland.