Presentation Given at May 4, 2022 Colloquium

Part of Educating Urban Ministers in Philadelphia After 2020 project

Presentation Question: What are the theological resources that we have drawn on and have found renewed relevance in during the crises of 2020 and will need to inform future theological reflection?

Introduction

I currently serve as Academic Dean and Clemens Professor of Missional Theology at Missio Seminary in Philadelphia, PA – but this has not always been so. My life has been a pilgrimage and has entailed a theological journey, not just at the school where I serve, but personally, and over the course of my life. The transition the school underwent to become the first evangelical seminary in the world to self-identify as “a missional seminary” and which then moved from suburbia to the heart of Philadelphia, is a transition that took me with it.1

Most of the resources I offer for your consideration today are resources picked up along the way of my own theological journey, amidst institutional struggle, and sometimes through personal angst. These are resources I now cherish; but this has not always been so.

Missio Seminary moved to Philadelphia in the fall of 2019. The pandemic hit in February 2020 and moved all classes fully online in March of 2020. The murder of George Floyd took place in May of 2020. The U.S. election that narrowly voted out Donald J. Trump and voted in Joe Biden and Kamala Harris was in November of 2020. By the end of December 2020, 345,000 people had died from Covid-19,2 the nation was in turmoil, and students and graduates, faculty and staff of the seminary were all conducting their ministries through digital technology and under significant stress.

This series of events tested, as by fire, the theological and ministerial resources that constitute the educational essence of Missio Seminary. I seek to offer you today what has emerged as gold and silver and also where our resources have proven not fully adequate or further resources are still needed.

Primary Theological Resource 1: Generous Orthodoxy

Missio Seminary, originally known as Biblical School of Theology, was founded in 1971 with a vision to train fundamentalist-evangelical pastors and leaders across denominational lines to revive the Church and evangelize the culture.3 At its founding, the school embraced (a generally) Reformed theology and premillennial eschatology, an amalgamation that in itself manifests the school’s original ethos, which deliberately fused together disparate elements of conservative, Bible-believing Christianity for common purpose.

In the 1990s, the founding faculty began to retire and were replaced by people who shared the convictions and ethos of “broader evangelicalism” but had not engaged in the fundamentalist battles, and were not insistent on maintaining doctrinal distinctives that alienated the school’s ministry from the larger Bible-believing Christian world. The inter-denominational quality of then-Biblical Seminary held potential still untapped – and even unsought – as long as the school maintained a narrow theological stance.

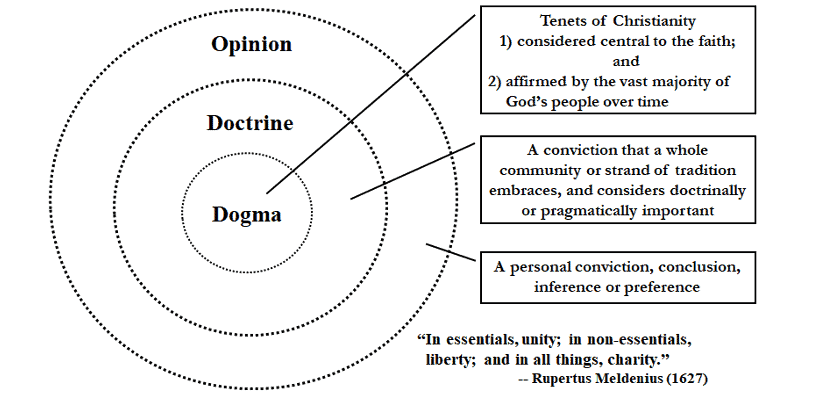

Premillennialism was dropped from the school’s doctrinal tenets in 1999. By the early 2000s, a broader theological path in general was taken. The new set of doctrinal convictions the school adopted in 2003 embraced what we have called ever since “Generous Orthodoxy.” Still self-identifying as an “evangelical seminary committed to the gospel of Jesus Christ,” Missio Seminary’s new doctrinal convictions embraced the spirit of the Vincentian Canon, affirming as dogma (only) “what has been believed everywhere, always, and by all,”4 with other doctrinal distinctives recognized and respected, but very few insisted upon.5

Let it be clear that in some ways we are still playing out the implications of this transition and, in some ways, are still even now in its throes. We cannot claim “demonstrated success” for a transition still so recent, and that, for all its worthy gains, has borne us some costs, too.6 That acknowledged, these are costs we now accept willingly as costs of the mission to which we believe God has called us and because of our shared theological conviction that underpins our stated theological conviction; viz. that the unity of the church and the coming together in pursuit of the mission is as important as doctrinal correctness.

The value of “Generous Orthodoxy” lies not just in its bringing clarity to certain core biblical and theological convictions, but also in its methodology, which provides a way for a Christian (or a Christian body) to adjudicate between what is most important and core to all versus what may be valued as important to one personally, or what may be important to an individual church or denomination, but may not be core to the Christian faith per se.

At root and at its best, generous orthodoxy successfully sorts mountains from molehills not just for expediency’s sake, but by successfully discerning the Spirit’s work in the history and life of the Church as a whole. Generous orthodoxy takes seriously Jesus’ promise that the Spirit would guide His disciples into truth7 – so that when we discern that the Spirit consistently has guided studied, prayerful, sincere, Spirit-indwelt people to consensus on 1) what is true; and 2) what is most important, those are points on which we can be confident that God, by His Spirit, has indeed spoken and made the truth clear.

We often hear the objection, “but different Christian groups agree on so little.” The historical theological data does not actually support this objection, however. A survey of church and denominational doctrinal statements and historic creeds quickly reveals significant agreement on core dogmas regarding the Trinitarian nature of God, the incarnation of Christ, God’s salvific purposes in the life, death, and resurrection of Christ, and the Holy Spirit’s powerful work of revelation and conviction until Christ’s return. It is true that Christians have fought frequently and split often over doctrinal disagreements and that points of dogma sometimes are challenged and have to be defended and sustained under duress. And yet, even still, look at what Christians consistently affirm, and one finds that the “dogma” category at the center of what constitutes generous orthodoxy is, in fact, a well-populated category.

One particularly valuable contribution of generous orthodoxy is that it gives us a place to put our disagreements that allows us to take those disagreements seriously, but without disabling us from working together to forward the mission of God in Christ in the world by the power of His Holy Spirit who indwells all of His children. Adopting the approach of generous orthodoxy allows us to invest our energies in pursuit of the mission rather than in competition and doctrinal argument. The legitimate place of doctrinal disagreement and doctrinal argument (fighting for the truth!) is not removed; it is put in its proper place.

As Missio moved into the city of Philadelphia, generous orthodoxy allowed us not only to marshal together people of different denominational affiliation for common purpose, but people of different races, different cultures. The theological recognition that people in other churches are, at root, brothers and sisters in Christ has enabled us to foster cooperation between people in churches some of whom had been at odds for years. Different from the liberal ecumenism of years past, generous orthodoxy allows a place for genuine biblical and theological disagreements to be acknowledged, recognized, and discussed – as we continue to work together towards common mission under the larger authority of Christ’s Headship and in pursuit of the larger mission.

Primary Theological Resource 2: Missional Theology

The missional movement is somewhat new and recent, although (as almost all missional theologians have pointed out) it is not, at its best, merely a faddish trend or set of buzzwords; it is bringing together and forwarding in new and focused ways themes both theological and practical that are as old as the mission of God. And while missional theology may frame some biblical concepts in new ways, the ideas are as old as the Bible itself.

The basic idea of missional theology is that God is on a mission to reach, reconcile, and redeem the world. That mission is holistic and transformative.

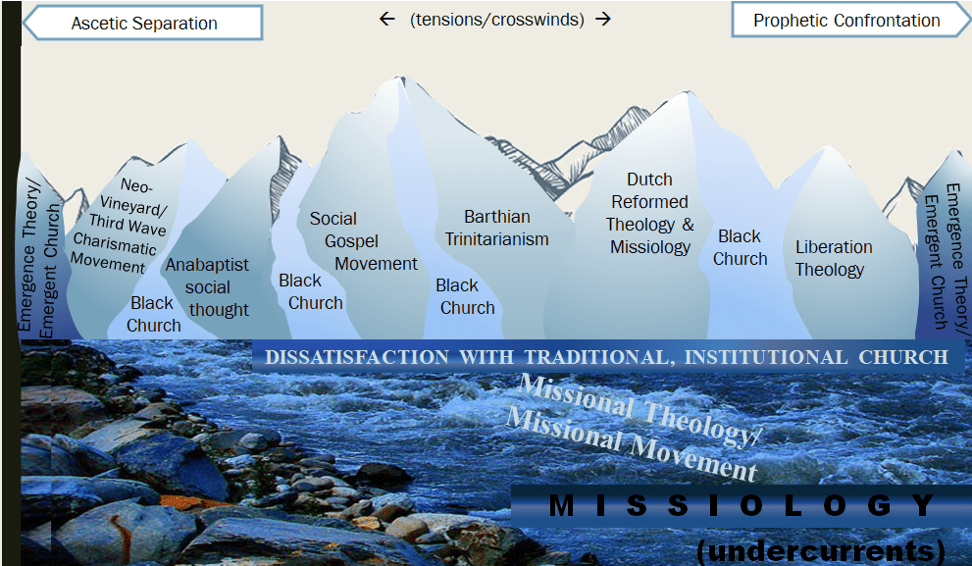

From this basic idea, different strands of the missional movement emphasize different aspects of what they deem as specific or most immediate goals of “the mission.” Laid out in a later picture is a taxonomy of missional origins.9 Perhaps it is worth noting that the further one goes to the left on this taxonomy, the more pacifistic is the orientation, and the greater the separation of church and state;10 the further to the right one goes, the more that taking hold of and transforming the societal structures of economy and government are considered part and parcel of the Christian “mission.”11

Before we delve deeper into that point, though, let us focus first on some of the true theological breakthroughs missional theology brings. Among them: God is not about the successful growth of a church, but the success of His Church in forwarding the Kingdom through all the earth, far as the curse is found. This understanding of “what the church is for” helps overcome other, lesser, defective conceptualizations of the church,12 such as:

- Church as performance art;

- Church as service provider for religious consumers;

- Church as self-help program;

- Church as religious education institute;

- Church as political action committee.13

Particularly when we reflect on the fact that “Kingdom” – as in “Kingdom of God in Christ” – inherently contains socio-economic implications that inherently suggest socio-political elements (but cosmic, and global, not national or nationalistic), the potential breakthroughs are even more dramatic. Jesus’ clarification that justice and mercy and faithfulness are among the weightier matters of God’s concern fits missional theology’s understanding of a gospel that pursues justice and righteousness in the here and now, not just pie in the sky by-and-by when we die.

Consideration of the plight of the poor – and how best to help the poor and disadvantaged and vulnerable – holds some promise for sharpening the thinking of missional theologians even further.15 It seems that missional theology, of late, has been moving in a more and more “Anabaptist direction.” This is probably understandable given the boorishly polarized political age in which we live. We can understand the instinct to just set aside and avoid as much as possible controversial socio-political questions when our goal is to just think more Christianly and behave more Christianly these days.16

On the other hand, missional theologians should understand better than most that the vast needs of the poor combined with the vast power of the government means that we really do need to give more than passing thought to the proper role and function of government in a fallen world, but a world in which we are increasingly seeking to extend God’s will – on earth as it is in heaven.

We also need to consider the role of private enterprise17 – including the role that private enterprise could play in bringing about the kind of culture and life and world that aligns with God’s will. We all (including missional theologians) must understand that giving to the government – or spending by the government – is not the same thing as “giving to the poor,”18 and that there is a possibility that government spending can actually be a detraction to greater prosperity and advantage to the poor rather than a benefit.19

Notions of “Christendom” have fallen out of favor – particularly among many missional Christians – and this is understandable, too, given the indecorous history of abuses, including wars and violent conflicts that often have accompanied allegedly Christian rulers presuming themselves to hold Divine rights of power and privilege. However, if principles of biblical Christianity are not deliberately and self-consciously fused with government social security and entitlement programs and policies, then what results is usually not something Christians (whether conservative or liberal, Republican or Democrat) can approve or applaud.20

Here is one point at which our theological resources have not proven fully sufficient. The political polarization manifested in the 2016 and 2020 election cycles has torn apart not only the American people but has divided Christian people, inflicting damage to the Body of Christ, as well as to the people themselves (knowingly or unknowingly).21 I am pleased that the collegial community of Missio Seminary has borne this together in considerable unity; perhaps we should recognize the remarkableness of this given its rarity.

What truly concerns me, though, is how difficult it now is to cultivate a constituency, or tap reliably into likeminded constituencies. There are now people claiming, in the name of “biblical truth,” that concern for social justice is something against which we should sound the alarm.22 I, for one, have been not just dismayed but genuinely surprised at how resistant have been large swaths of self-described “Bible-believing Christians” to biblical lines of reasoning on such issues. I can understand the reasoning that says, “In a choice of two evils, I am seeking to choose, with a heavy heart and tear in my eye, the lesser of the two”; but I genuinely just do not understand the gleeful enthusiasm for and shameless support for what is clearly outside the character and moral will of God.

We still need further resources to address and overcome this. Or, is it that we currently are just in a pretty dark place in our history as a country – as a world – and are simply being called to forbear and endure and persevere to the end, serving as faithful remnant and prophetic witness thereby?

Primary Theological Resource 3: Training Counselors Attuned to their Ministry as Being an Aspect of the Mission of God

Missio Seminary is not the only school that trains “Christian Counselors.”23 Missio is distinct, though, in training Christian Counselors as one aspect of training missional leaders. Our counseling program is not just an appendix, a side field or after-thought. The training and personnel are part and parcel of the missional education.

The merger of biblical wisdom with the insights from the field of psychology folded into an overall vision of how these skills foster healing and maturity and growth as an endeavor of God’s mission represents perhaps one of the most practical “theological resources” I could mention. The story of how Missio Seminary moved from a nouthetic, “biblical counseling” approach to a more integrative “Christian counseling” approach is itself an interesting story. The details are beyond the scope of our focus here, but I will say that, in many ways, the counseling department was first and led the way in helping shape our overall theological and ministry training approach. The counselors were the ones to discover early that providing Spirit-prompted help to people as part of the ministry of Christ to His people and to the world is something that transcends denominational line and theological differences. Christians cooperating and integrating competencies to provide such ministry is something that takes on a life of its own, and seems to tap into larger purposes of God.

At Missio, recognition and embrace of the larger mission of God would eventuate from such insight – the practice of which came first, actually, even before the larger theological understanding of “why.” That, in itself, may have profound significance.

Primary Theological Resource 4: The Diversity of Our Backgrounds, Joined and Merged in a Single Missional Educational Ministry Training Institution

Not to be overlooked as a significant “theological resource” is the unique kind of community God has forged at Missio Seminary through this time of turmoil and trial. I am now the longest-serving employee at Missio Seminary; as such, I can remember when the entire staff was all white, and the entire faculty was white, male. This was not something conscientiously imposed, but happened “naturally,” organically, one might say. Diversifying, on the other hand, was something that was pursued quite deliberately, as part of our vision which stemmed organically from our mission. Today, we are a community that is just about evenly distributed between Caucasian, African-American, and Asian.

Part of our ethos at Missio is constituted by our cherishing this diversity, and recognizing that this diversity joined together in shared ministry makes us part of something rare and precious. At its best, whether in the classroom or in a faculty or staff meeting, the community dynamic at Missio is just electric – stimulating and edifying. This is genuinely the truth, and should not be cynically ignored when I move to reflect on what you can guess is coming next. Sometimes, the racial and ethnic and cultural tensions we see all too often reported in the world at large rise up in our relationships to one another at Missio Seminary, too. The difference is that we are engaging these tensions while still joined together in a larger mission of God, which we all really, genuinely share in the larger picture.

And so, the struggles and disappointments and wounds shared in such books as Ed Gilbraith’s Reconciliation Blues: A Black Evangelical’s Inside View of White Christianity,24 Michael Emerson and Christian Smith’s Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America,25 Jemar Tisby’s The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism,26 and Esau McCaulley’s Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation as an Exercise in Hope27 have been part of the growth process at Missio Seminary, too. I am grateful for these books and they are excellent resources. The truth is, though, I was privileged to learn of most of the principles and points conveyed in these books first by trusted friends and colleagues before I read them in these books.

Missio Seminary has engaged in some “courageous conversations” – both public and before the cameras.28 The more valuable and more courageous conversations, however, actually have taken place privately, with no cameras rolling, and with truth being exchanged not just proclaimed or virtue-signaled.

Conclusion

I am pleased to observe and offer these resources, each and every one of which has been developed or simply “come our way” at Missio Seminary in pursuit of training missional leaders, particularly through the crises of the 2020 era. All of the resources come to you having been genuinely field tested, though some admittedly are under development or stand in need of further development or adaptation to specific contexts. Perhaps this is where you come in.

Notes

1 My upbringing in the small town of Mechanicsville, VA (a suburb of Richmond) represented a demographic not all that different from the small town of Hatfield, PA, the original location of Biblical Theological Seminary (now Missio Seminary). The transition and move of the school meant taking stock even of my own, personal identity. The school is now in the heart of a global city where I am still not completely comfortable. James Spencer’s study of cities as “global urban ecosystems” helped me make my peace with being a “commuter,” vis-à-vis a native born Philadelphian (“old-timers”), or a settler (“do-your-timers”); see James H. Spencer, Globalization & Urbanization: The Global Urban Ecosystem (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015).

2 This data is from the Centers for Disease Control (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7014e1.htm).

3 My own affiliation with the school started in 1975, when my mother began working at the school as a secretary in the president’s office and in the development office. (I was a teenager, in Jr High School, but was introduced to the school’s faculty, staff, and ethos even then through my mother.) The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania had granted the school the right to award degrees in 1974; the school changed its name to “Biblical Theological Seminary” in 1978. In 1984, I enrolled at Biblical Seminary as a student, and graduated with an MA and MDiv (1988), and an STM degree in 1990. I was invited onto the faculty in 1998. (I was finishing up my PhD at Dallas Seminary, which I completed in 2001). I served as dean of the faculty, 2006-08, and then Academic Dean from 2008 to 2017. Currently, I am the Les and Kay Clemens Professor of Missional Theology, the Academic Dean, and the longest tenured employee at Missio Seminary. My recounting of the history at Missio is from personal recollection (I was there, in the meetings, etc.), with my recollection assisted, supported, and corroborated by notes in my files, as well as meeting minutes, faculty and staff handbooks, catalogues, and brochures accessible in the seminary’s archives.

4 This was framed famously as the “three tests of catholicity” by Vincent of Lérins, Commonitorium, 404 A.D., in Documents of the Christian Church, ed. Henry Bettenson and Chris Maunder (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), “Section IX: Doctrine and Development. The Vincentian Canon,” 88-90. We recognize a degree of epistemological naiveté in Vincent’s framing. Nevertheless, the basic gist and intent we still find to be solidly correct, and its essential logic is what forms the heart of what we mean by “generous orthodoxy.”

5 Missio Seminary’s “Convictions Statement” can be found on the school’s website at https://missio.edu/ convictions-statement/.

6 While the broadening of our theological positioning seemed to help our student enrollment at first, about a third of our donors at the time dropped out, a loss from which we are still recovering. We are aware that similar disruptions and losses have been faced by our grads who have led their churches through a similar transition, either to a more generous theological posture towards other Christian churches or denominations or to adopt a more missional understanding of the role and function of the church (taken up below).

7 John 16:13.

8 The “dogma, doctrine, opinion” framing was first proposed by Stanley Grenz and Roger Olson, Who Needs Theology?: An Invitation to the Study of God (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 1996), 73-77, a book of thoughtful hermeneutical and theological insights, but really written for a popular or collegiate-level audience. Though not demarcating the categories of dogma, doctrine, and opinion, per se, a careful and scholarly presentation of the viable role of tradition and the historical theological work of church (as manifestation of the Spirit’s guidance) is provided by John R. Franke, in Beyond Foundationalism: Shaping Theology in a Postmodern Context (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2001), 113-29. These framings formed the heart of Missio Seminary’s embrace of “generous orthodoxy” in the early 2000s, where Franke served at the time as chair of the theology faculty and, as such, was influential in the school’s theological transition. Perhaps regrettably, Franke’s own theological thought moved more and more in a postmodern and deconstructionist direction (cf. John R. Franke, Manifold Witness: The Plurality of Truth [Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press, 2009], which led him eventually to leave Missio Seminary) and landed him fully in the mainline church. His most recent work (Missional Theology: An Introduction [Grand Rapids: Baker, 2020]), while an excellent introduction to missional theology and a missional approach to ministry (taken up, below), does not capitalize as much as it might on the earlier insights Franke himself actually laid out in Beyond Foundationalism. In the more recent work (Missional Theology), he emphasizes much the diversity and multiplicity of perspective in God’s One Church, but without the ballast the boundaries of dogma his earlier writings suggested could be reliably provided by the historical theological work of the Church.

The phraseology of “generous orthodoxy,” honestly, was about ruined for evangelical usage when Brian McLaren published a book by that title in which he advocated an approach highly resembling simple classical liberal ecumenism (see Brian McLaren, Generous Orthodoxy: Why I am a missional, evangelical, post/protestant, liberal/conservative, mystical/poetic, biblical, charismatic/contemplative, fundamentalist/Calvinist, Anabaptist/Anglican, Methodist, catholic, green, incarnational, depressed-yet-hopeful, emergent, unfinished Christian [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004]). May I suggest that, without the Vincentian historical-theological grounding of dogma, “generous orthodoxy” can tend to be high on generosity but low on orthodoxy, a tendency we still confront regularly as a seminary.

9 For origins of missional theology, see David J. Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1991). This may be the best single volume insofar as presenting the ideas of missional theology. This work certainly has highly influenced the whole “missional movement” to this day.

Bosch’s background was Dutch Reformed. This in itself bears some notice. The Dutch Reformed theology of Abraham Kuyper – who merged church and state enough to become Prime Minister of Holland [!] – is noteworthy. His writings (e.g., Common Grace; Proper Christian Education; and Pro Rege) articulates how the reign of Christ should be reflected in the reign of Christian human government, too. One statement by Kuyper is often quoted, including by missional theologians, as encapsulating the goals of the mission of God: “There is not a square inch in the whole of creation over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’ There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’” Kuyper really meant this; even though some readers of Kuyper have clarified that these are “Christ’s realms” not Christians’. I am not sure that Kuyper himself would have so emphasized such a distinction. In any case, the Dutch Reformed theology of Kuyper (and Bavinck, and the Ridderbos brothers, etc.) has had a significant influence on the formation of missional theological ideas. Of course, one could look at the debaucherous, post-Christian state of Holland today and legitimately wonder whether Kuyper’s ideas are really worthy of recovery, much less redeployment. Before blaming Dutch Reformed theology for Holland’s contemporary state, though, it is only fair to observe all of Europe, not just Holland, has fallen into a post-Christian antipathy towards Christian values; and we should also recognize that the Nazi occupation of Holland in the mid-20th century did not help its Christian maturation, either [!]).

At any rate, David Bosch’s background in Dutch Reformed theology was as an “Afrikaner” in South Africa who came to oppose Apartheid, and, in fact, invested much of his life to ministering to black South Africans struggling under the oppression of South Africa’s racist structures. This background reflects the passions and commitments of several other missional or “proto-missional” theologians, as well. Walter Rauschenbusch served as a pastor among the urban poor in Hell’s Kitchen, New York. Lesslie Newbigin invested much of his life as a missionary to India. Bosch and Newbigin were also influenced in their theological understanding by engagements with Barthian Trinitarianism (though Oscar Cullman was a greater influence on Bosch). Harvie Conn, likewise, was a very conservative, Dutch Reformed theologian, who served for decades as professor of missiology at Westminster Theological Seminary. Before coming to teach at Westminster, he served as a missionary to the urban poor in South Korea. By his own testimony, Conn’s outlook on theology and ministry – in fact, his whole outlook on life! – was highly impacted by his work among these poor people, particularly his work among the street people and prostitutes living on the streets of Seoul. At one point, he and Bosch actually joined together in a writing project; the compendium of missiological, missional theological ideas is contained in Missions & Theological Education in World Perspective, ed. Harvie M. Conn and Samuel F. Rowen (Farmington, MI: Associates of Urbanus, 1984); cf. Harvie M. Conn and Manuel Ortiz, Urban Ministry: the Kingdom, the City, and the People of God (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2010).

John G. Flett traces the history of the missional movement through the interaction of the German Reformed (Barth among them) and the (social-gospel oriented) Anglo-Americans at significant missiological and ecumenical conferences throughout the early to mid-20th century (The Witness of God: The Trinity, Missio Dei, Karl Barth, and the Nature of Christian Community [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010]). Other accounts that trace the origin of missional theology through the German Reformed (and Lutheran) include Patrick Kiefert, We are Here Now: A New Missional Era (Eagle, ID: Allelon, 2006); and Craig Van Gelder and Dwight J. Zscheile, The Missional Church in Perspective: Mapping Trends and Shaping the Conversation (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2011). John R. Franke traces this history similarly (Franke, Missional Theology: An Introduction [Grand Rapids: Baker, 2020]).

10 Stanley J. Grenz represents a Baptist pioneer of the missional movement; he credits both Rauschenbusch and Wolfhart Pannenberg with setting the direction of his theological pilgrimage. (See Grenz, Created for Community: Connecting Christian Belief with Christian Living [Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996]; and idem., Theology for the Community of God [Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman, 1994].

The influence of Anabaptist ideas into what eventuated in the missional movement can be traced to the work of John Howard Yoder, The Politics of Jesus: Vicit Agnus Noster (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972). Yoder’s work highly influenced the thought and writings of later well-known Anabaptist (or Anabaptist-ish) thinkers such as Ron Sider (Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger: Moving from Affluence to Generosity [Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1997]) and Tony Campolo, Red-Letter Christians: A Citizen’s Guide to Faith and Politics [Ventura, CA: Regal, 2008). An example of the fusion of Anabaptist and neo-Vineyard/Third Wave Charismatic ideas in interaction with Barthian Trinitarian (and other streams of the missional movement) is Cherith Fee Nordling, daughter of renowned Pentecostal theologian Gordon Fee; see Cherith Fee Nordling, Knowing God by Name: A Conversation between Elizabeth A. Johnson and Karl Barth, Issues in Systematic Theology, Vol. 13 (New York: Peter Lang, 2010). She, along with David E. Fitch (see Fitch, The Great Giveaway: Reclaiming the Mission of the Church from Big Business, Parachurch Organizations, Psychotherapy, Consumer Capitalism, and Other Modern Maladies [Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005]; also idem. and Geoff Holsclaw, Prodigal Christianity: 10 Signposts into the Missional Frontier [San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013]; and idem., The End of Evangelicalism? Discerning a New Faithfulness for Mission: Towards an Evangelical Political Theology [Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2011), have been prominent leaders of the Missio Alliance network, headquartered in northern Virginia. Notice (particularly in the progression of books by Fitch) how the socio-political ideas seek to be prophetic, but also more and more Anabaptist in flavor.

11 Ross Douthat is one of the few to recognize and list the African-American Church as a distinct ecclesiology alongside American Evangelicalism and Roman Catholicism, in his socio-historical analysis of how religion in the U.S. has degenerated from a force of intellectual vigor and cultural fiber to a sloppy blend of ideological pragmatism and solipsism (Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics [New York: Free Press, 2012], 44-54). Likewise, liberation theology is often overlooked in regard to its contribution of ideas to missional (or at least “proto-missional”) theology, an omission that Franke, in particular, seeks to correct (op. cit.; also Manifold Witness: The Plurality of Truth [Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 2009]). See James Cone, God of the Oppressed (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1975); idem., The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2011). Cf. also Drew Hart, Who Will Be a Witness: Igniting Activism for God’s Justice, Love, and Deliverance (Harrisonburg, VA: Herald Press, 2020); Hart prefers the nomenclature of “Anablacktivist” to describe himself and his theological positioning, which, in itself, helps explain (and justify) some of the terminology used and the positions framed out in the taxonomy on page 10.

Liberation theology (and black liberation theology in the U.S., in particular) represents a loud and militant sort of movement, which has gained much notoriety. In existence before this movement and still often alongside it has been the black church. Discovery of the black church came for me (a white male, born, raised, educated, and making my career in white suburbia) admittedly pretty late in my career and thought, but it has “always” been here, since people of color came into North America, most against their will, often in chains and shackles. Even the most conservative (biblically and theologically) black churches, given the context of hardship, deprivation, and oppression of their origins, have and have always had a social service element in its conceptualization of the proper role and function of the church and an active pursuit of social justice in its theological orientation.

Anecdotally, I can report that, when Missio Seminary first launched its urban program and opened its first satellite campus in the city (at “Joy in the City,” in the Hunting Park section of Philadelphia), we would teach what we thought were the edgy, “revolutionary” insights of missional theology. We believed we were offering an expansive, fresh understanding of God and God’s work in the world. Dare we even broach how even “the gospel” might need fresh understanding, given God’s missional purposes? On more than one occasion, when I was finished presenting what I thought would be “highly controversial” material on how the New Testament (Jesus in particular) frames out a gospel that demands concern for righteousness and justice – not just forgiveness and mercy – African-American students (many of whom, though new to seminary, actually had been pastoring churches for years) would respond nonplussed with statements like, “Well, yeah; ‘word and deed gospel’; we’ve had that in the charter statement of our church for years” [!]. The language and framing of “missional theology” might have been (and still might be) new to black church leaders, and I would still like to think that the systematic framing out of missional theology might still add some contribution to their theological understanding and might still have value for their ministry, but the truth is: some of the most significant practices that missional theology aims to foster actually already have been embraced in the thought and practice of the African-American church, probably for centuries.

See the webinar led by my Missio Faculty colleague, Clarence Wright, “Hands on the Gospel Plow: The Missional Work of the Black Church” (https://missio.edu/hands-on-the-gospel-plow-webinar/, broadcast and recorded February 28, 2022).

For scholarly examinations and explanations of the history and character of the black church, see C. Eric Lincoln and Lawrence H. Mamiya, The Black Church in the African American Experience (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1990); Robert Kellemen and Karole A. Edwards, Beyond the Suffering: Embracing the Legacy of African American Soul Care and Spiritual Direction (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007); Carl F. Ellis, Jr., Free at Last?: The Gospel in the African-American Experience (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 1996); Glenn Usry and Craig S. Keener, Black Man’s Religion: Can Christianity Be Afrocentric? (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 1996); Wayne E. Croft, Sr., The Motif of Hope in African American Preaching During Slavery and the Post-Civil War Era: There’s a Bright Side Somewhere (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017). Also see Howard Thurman, Jesus and the Disinherited (Boston, MA: Beacon, 1976). Cf. also the extremely negative account of the influence of the Black Church in African-American life conveyed by James Baldwin, Go Tell It on the Mountain (New York: Vintage, 1952).

12 For sources expanding on this point, see Darrell Guder, Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998); idem., The Continuing Conversion of the Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000); James C. Wilhoit, Spiritual Formation as if the Church Mattered (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008); Ross Hastings, Missional God, Missional Church: Hope for Re-evangelizing the West (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2012); Adam L. Gustine, Becoming a Just Church: Cultivating Communities of God’s Shalom (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2019); Banseok Cho, Being Missional, Becoming Missional: A Biblical-Theological Study of the Missional Conversion of the Church (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2021).

13 There is no question that much noise has been made – much provocation and much controversy incited! – by “the emergent church,” “emergent village,” and “the emergent movement,” which, I suppose, is still generating heat in some quarters, but I believe has largely run its course. The “emergent movement” has had influence on “the missional movement,” though its influence often has been overestimated and overstated. In truth, its controversial, provocative nature gave it far more attention than it probably merited, also considering that “emergent leaders” such as Brian Maclaren and Rob Bell and Tony Jones and Mark Driscoll “dramatically evolved” over the course of time, their positions growing mercurially more provocative with their fame. For a fair accounting of “emergents’” ideas and influence, see the surveys and analyses by Eddie Gibbs and Ryan K. Bolger, Emerging Churches: Creating Christian Community in Postmodern Cultures (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2005); and Scot McKnight, “Five Streams of the Emerging Church: Key elements of the most controversial and misunderstood movement in the church today,” Christianity Today 51/2 (February 2007), 35-37. Fig. 2 incorporates McKnight’s analysis in part; notice that I have placed “the emergent church” on both extreme ends, representing “cold streams” feeding “the missional river,” with influence thin but dramatic. “Emergents” sometimes have called for prophetic overthrow of principalities and powers of church (and government, too) and sometimes called for radical separation into enclaves of power-deflecting communes. (See Shane Claiborne, The Irresistible Revolution: Living as an Ordinary Radical [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006]; idem. and Chris Haw, Jesus for President: Politics for Ordinary Radicals [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008]; idem. and Tony Campolo, Red-Letter Revolution: What if Jesus Really Meant What He Said? [Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 2012]). Claiborne has not just advocated for such ideas, he (to his credit) practices them, with a group of like-minded disciples in a row home in a poor, crime-and-drug infested neighborhood in the Kensington section of Philadelphia, PA. Acknowledging that some of these ideas are radical strands (as they themselves proudly declare, actually [!]), I am here seeking accurately to include the emergent church’s notoriety and influence, while also conveying that, despite the disproportionate attention given to it, the actual influence of the “emergent element” on the missional movement, in truth, has always been marginal.

14 Matthew 23:23.

15 “Creative destruction,” with its brutal displacement of workers’ livelihoods, was one point of Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism in Das Kapital (1867). Joseph A. Schumpeter elaborated on these dynamics of “creative destruction” with similar concern (Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy [London: Routledge, 1942]). Suffice it to say that, once the degree of economic brutality was recognized as inherent to free market capitalism – which can be downright cruel to workers just trying to make a dignified livelihood – much discussion and debate ensued regarding how best to relieve the suffering of workers displaced by free market creative destruction. It should be mentioned that there is an economic case to be made against trying to intervene at all – that attempts to intervene (by government intrusion and disruption of free-market forces), though well-meaning, commonly (inevitably?) end up doing more harm than good. (This is one argument of Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty [New York: Crown Business, 2012]; it is a cost-benefit analysis, concluding that the cost of governmental intervention in free-market forces [with the invariable penchant for corruption in the process notwithstanding] is way too high given the extraordinary benefits overall and in general to allowing the forces of a free-market economy simply to play out.

I observe in passing that I find it curious that these discussions have taken place consistently in the context of highly affluent American culture and almost exclusively among economists and politicians, with Christian thinkers seemingly weighing in only afterward – and marginally at that. I can only assume this is because the separation of church and state has been assumed so early and so thoroughly in our history and thought (to this day).

16 I have mentioned my disappointment in how American Christian thinking has been lacking. Let me also mention works I have found helpful, whose ideas I believe get a start on some of the topics raised in this paper worth building on; viz. Andy Crouch, Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2008); and idem., Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2013); Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theology (Notre Dame, IN: University Press, 1981); and idem., Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (Notre Dame, IN: University Press, 1988); and James Davison Hunter, To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

17 Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s, famously said, “If any of my competitors were drowning, I’d stick a hose in their mouth and turn on the water. It is ridiculous to call this an industry. This is not. This is rat eat rat, dog eat dog. I’ll kill ’em, and I’m going to kill ’em before they kill me. You’re talking about the American way – survival of the fittest.” American Christians really need to ask: is this attitude really to be admired? Is this to be embraced and emulated as a core American value? Are these Christian values being upheld here? Moreover, is it really true that our business practices that form our livelihoods and in which we spend a goodly portion of our waking hours throughout most of our adult lives really have nothing to do with Christian values and biblical teaching per se?

There are some good books on how biblical-Christian values can and should be merged in ways better than Kroc’s quote does, of course. Among them: Jeff Van Duzer, Why Business Matters to God (And What Still Needs to Be Fixed) (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2010); and Tim Voorhees, Joyce Avedisian-Riedinger, and Mike Pendleton, Reflecting God’s Character in Your Business (Houston, TX: High Bridge Books, 2019).

The hard question still remains: can and should business done by Christians be explicitly Christian – engaged in pursuit of forming more and more a Christian culture and society? We realize that, if so, or at least to the extent that the answer is “yes,” to that extent is embraced the very definition of “Christendom.” We are back again at the root question: have the failures of “Christendom” been due to the root idea being wrongheaded? Or a failure of execution of what is still basically good and right in concept? (I contend again: this is a harder question than often recognized.)

18 Milton Friedman’s analysis is now (in)famous; he argued that: 1) money used by the government is money that (does not come “from nowhere” but rather) is money extracted from the economy; and 2) there is little that the government does that cannot be done with more efficiency, with greater accountability and thus with greater quality by the non-government sectors of the free-market economy and voluntarily supported charitable organizations. See Milton Friedman, Capitalism and Freedom (Chicago: University Press, 1962 – with several revised and updated editions following). This conclusion is shared and expanded by Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail.

19 This point is made well by Arthur C. Brooks, Who Really Cares: The Surprising Truth about Compassionate Conservatism – Who Gives, Who Doesn’t, and Why It Matters (New York: Basic Books, 2006); Steven Corbett and Brian Fikkert, When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and Yourself (Chicago, Moody, 2009); Robert D. Lupton, Toxic Charity: How Churches and Charities Hurt Those They Help, And How to Reverse It (San Francisco: Harper One, 2011). The inadvertent driving to dependency (rather than liberation) surfaced and analyzed in these books that can happen with well-meaning (but wrong-headed) donations and charities has a corresponding and a fortiori parallel in the public sector, as well – particularly as regards financial aid programs, either foreign or domestic. These dynamics are a focus of attention of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and also the Acton Institute. (A visit to the websites of either of these groups makes available an abundance of research and resources, including books and articles, besides the websites’ own statistical and ideological analyses.

The conclusion rendered by much of this research echoes the point made by Rev. Robert Sirico (of the Acton Institute), “The most compassionate thing one can give to a poor person is a job.” This axiom fuels much of the Acton Institutes ideas and efforts, with a general understanding underpinning it all that creating a good, growing economy – supporting capitalistic business development and the growth of businesses – also increases jobs and income and wealth, which makes government relief efforts less necessary, and, many of these advocates would argue, exposes how government relief efforts, which are funded by undermining these private-sector enterprises and economic growth dynamics, are ultimately wrong-headed.

20 We have cited above numerous examples of blunders left and right over the course of our discussion of these issues. Here let me list just one more: when church is separated from state, and yet the state is charged with social welfare issues, then what can result is barbaric murder of in utero human beings being deemed simply an aspect of “health care.” Is the problem here that the government should not be involved in health and human welfare at all? Or that Christian values should have more influence than they currently do on such involvement? We see that those are very different answers to the question!

21 A collection of essays that makes this point bluntly is The Spiritual Danger of Donald Trump: 30 Evangelical Christians on Justice, Truth, and Moral Integrity, ed. Ronald Sider (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2020). The authors of this book in the aggregate may “lean left” politically, but every contributor self-identifies as an “evangelical”; both Republicans and Democrats are included on the roster of essayists in this volume, including a couple of self-described “conservative” evangelicals.

22 E.g., Jon Harris, Social Justice Goes to Church: The New Left in Modern American Evangelicalism (Greenville, SC: Ambassador International, 2020); Voddie T. Baucham, Jr., Fault Lines: The Social Justice Movement and Evangelicalism’s Looming Catastrophe (Washington, DC: Salem Books, 2021).

23 The nomenclature here is deliberately chosen. “Christian Counseling” is distinct from what is called in the literature “Biblical Counseling” (on one end of the spectrum) or “Christian Psychology” (on the other end of the spectrum); see Eric L. Johnson, ed. Psychology and Christianity: Five Views (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2010; and Stephen P. Greggo and Timothy A. Sisemore, Counseling and Christianity: Five Approaches (Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2012).

24 Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2006.

25 New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

26 Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2019.

27 Downers Grove, IL: IVP, 2020.

28 See https://missio.edu/?s=courageous+conversations.