Narrow Gates and Discipleship

A narrow gate is more difficult to pass through than a wide gate. So why take the narrow gate? Christ once charged his disciples with these words: “Enter through the narrow gate; for the gate is wide and the road is easy that leads to destruction, and there are many who take it. For the gate is narrow and the road is hard that leads to life, and there are few who find it.”1

For years I interpreted that passage primarily in soteriological terms (i.e. solo Christo, saved by Christ alone). That is, Christ was essentially referring to himself as the narrow gate that leads to life; thus, I simply needed to believe and remember what Christ accomplished at the cross and not necessarily look for and enter narrow gates myself, literally and spiritually. As a result, rarely did I interpret the passage in terms of discipleship, though a couple chapters prior in Matthew 5:1-2 the reader is reminded of the context of Matthew 7, namely that Christ was illuminating to his disciples not simply principles to conceptually embrace, but the cost of life in the kingdom of God.2

On the one hand, “taking the narrow gate” is in part a commentary on soteriology. There are countless roads that offer us fullness of life, options that many equate with salvation—money, career, spouse, children, just to name a few. Yet Christ is unwavering in his proclamation that he alone is the way to life (e.g. Matt. 10:32-39; Lk. 9:21-27; Jn. 6:60-71; Jn. 10:1-10; Jn. 14:1-7). Therefore, to trust in Christ as lord and savior is to take the narrow gate. On the other hand, and seen through the lens of discipleship, “taking the narrow gate” is also about the daily decisions we make as followers of Christ, and how those decisions bear witness to our love for God and others; decisions that call us to die to ourselves for the sake of Christ. To take the narrow gate, then, is to both trust and follow Christ.

As those who identify as Christians, we can often underestimate the attraction and convenience of wide gates (e.g. taking the less other-centered, less self-sacrificial way). We might preach and trust in Christ for our eternal salvation, but to die to ourselves and live to Christ each day is another matter.

For churches that aspire to be hubs of multicultural ministries and address polarizing issues like immigration and overcriminalization, this task can be even more tense and harrowing considering that it is comparatively easier to do ministry with those who approach life similarly than with those who might have different philosophies and priorities.

In terms of our following of Christ, the narrow gate will include the trivial and substantial decisions that we make. Some of those decisions might include acts of service in your household, congregation, and community; showing mercy to those who have wronged you; asking for forgiveness when you have wronged someone; and being a person of integrity when others are dishonest. In other words, every decision we make as followers of Christ is in some shape or form an act of discipleship. While much more can be added to this list, one that is commonly avoided and often neglected is lament.

Discipleship as taking the narrow gate describes daily decisions we make to die to self–one that is often avoided and neglected is the practice of lament.

The Absence of Lament in Discipleship

As a chaplain who works in both a hospital and a university setting, it is no longer surprising to me to see people react to the word “lament” in one of two ways. Folks will either stare quizzically at me and wonder what is meant by that word as if it was gibberish, or they will be dismissive of it having quickly associated lament only with grieving the loss of loved ones. Both responses are pervasive, and both are often a result of having had little to no interaction with biblical lament.

In the last few decades, there has been a resurgence in Christian scholarship on lament. Within that period, Walter Brueggemann has been among the most prolific scholars to write on the value of lament for faith and worship in evangelical Christianity.3 More recently, authors such as Soong-Chan Rah and Mark Vroegop have also contributed provocative pieces on lament.4 The overarching message from each of these authors is that lament is a form of prayer and worship in difficult times that can enrich the spiritual health and vitality of the people of God as it creates space for us to cry out to God in faith and dependence on him as well as move us out towards the hurting. This act of dependence on God is arguably essential to the life of the Christian. Yet, barring large scale tragedies, lament remains mostly absent in our ministries and discipleship.

There are at least three reasons why lament tends to be neglected in our churches. First, the influence of classical Greek on Christendom, and its preference for logic and order over emotion and disorder, still lingers. In his reflections on the lack of lament in Western Christian traditions, Claus Westermann—a twentieth century Old Testament scholar who helped the church to distinguish between psalms of praise and psalms of lament—offered this observation:

It would be a worthwhile task to ascertain how it happened that in Western Christendom the lament has been totally excluded from man’s relationship with God, with the result that it has completely disappeared above all from prayer and worship. We must ask whether this exclusion is actually based on the message of the New Testament or whether it is in part attributable to the influence of Greek thought, since it is so thoroughly consistent with the ethic of stoicism.5

Although laments are seemingly few and far between in the New Testament, one can still find traces and fragments (e.g., Christ’s passion narrative; Rom 8:18-25; 2 Cor. 12:1-10). And while there might be more passages that emphasize praise and rejoicing, there is no passage in the New Testament that substantially discourages or discredits lament. Perhaps, then, Westermann is right to observe that a lack of lament in the church has less to do with the treatment of the subject in the New Testament and more to do with the ongoing effects of a once dominant culture (i.e., Greek thought) on our interpretation of scripture.

A lack of lament in the church has less to do with the treatment of the subject in the New Testament and more to do with the ongoing effects of a once dominant culture on our interpretation of scripture.

On a side note, church traditions that emphasize stories and emotion seem to move more freely towards lament than churches that primarily focus on intellectual assent to doctrinal propositions. For example, the Negro spirituals (laments forged in the crucible of slavery in the United States and which contributed to the culture of many black churches in America) are historically a hybrid of African / African American traditions and Christian worship.

Second, lament is disruptive. It signals that something is wrong. It is a reminder that there is brokenness in this world. It acknowledges that pain and suffering cannot easily be scripted out. It is a cry of the soul when all else fails. And, it upsets the status quo. Scott Ellington contends:

Because they are such intense expressions of pain, laments are uncomfortable for those standing by who cannot share directly in the experiences of the person praying. They open the listener to participation in the experience of the speaker. They speak too frankly and bear too much of the soul of the person praying, and they remind us that we can each find ourselves in a similar situation. So, it is not surprising that we should seek to avoid prayers of lament at those times when our lives are in balance.6

A life that is stable and comfortable is the default preference and pursuit for many. Closely related is the freedom to decide how much one gets involved in unstable and uncomfortable situations. I am often reminded of the wide-scale musical event in 1985 called Live Aid. From one perspective, this was a charity event in which famous bands and musicians were invited to perform in a day-long global broadcast to raise funds for humanitarian efforts in Africa; later billed as one of the greatest events in concert history. From another perspective, this was a classic example (albeit on a macro scale) of how we manage lament and hardship. That is, when confronted with crises, we major on finding stability and comfort (e.g., feel good moments; success stories) and minor on incarnational ministry (e.g., taking time to understand the context of those hurting; giving our lives and not just money).

Lament is disruptive because it signals that the way things are is broken. Lament upsets the status quo. Hence the dominant avoid it.

In contrast, lament involves pain and sharing in the suffering of others. And with it, undefined seasons of instability and discomfort. It will conflict with our sense of progress and control. As a result, lament tends to be out of sight, out of mind, whenever possible. For those in the dominant culture and who have access to resources and networks, this translates into minimizing instability and discomfort in their lives in ways that far surpass the efforts of those in the subdominant culture and who have less resources and networks. As a result, lament is like a bridge frequently crossed (or at the very least visited) by the poor and powerless but avoided for long periods of time by the rich and powerful.

Finally, lament tends to be neglected due to a narrow vision of it. Lament usually signals distressful situations. However, biblical lament is about more than the situation; it is fundamentally an encounter with the triune God. Consider the following examples from the Old and New Testament. In the Exodus account, Moses cried out often to God despite the trail of miracles God routinely produced in a variety of situations (e.g., Ex. 15:22-25; 17:1-7; Num. 11:4-15). In the story of Ruth, Naomi expressed her anger with God, in light of losing her husband and sons, by insisting that the town call her Mara which means bitter (Ruth 1). In the psalms, David—the man after God’s heart—lamented before God time and again (e.g., Ps. 6; 13; 22; 70). In the gospels, Christ revealed himself as one who was no stranger to lament (e.g., Matt. 26:36-46; Lk. 19:41-44; John 11:28-37). And in the Pauline epistles, the apostle Paul lamented before God though he knew God’s decision on his situation (2 Cor. 12:1-10).

Given our tendency to neglect lament, there is a constant need to revisit and reimagine how lament might inform our lives, individually and corporately. Further, much of our efforts towards reconciliation and unity in our churches and communities are unlikely to last in any sort of significant way if lament is absent. This is not to say that lament is the antidote to sin and suffering. Rather, that lament is movement towards the God whose presence brings the hope and healing that we so desperately need.

Much of our efforts towards reconciliation and unity in our churches and communities are unlikely to last in any sort of significant way if lament is absent.

It is this idea of movement towards God that I want to emphasize in our discussion on lament. Most contemporary books and articles on lament primarily stress lament as a prayer and liturgical response; and regarding discipleship, a formal corporate prayer of confession. While some measure of formality is appropriate, scripture also leaves room for lament to be fluid and organic (i.e., constantly adapting and adjusting). This article will offer a nuanced definition of lament: lament is movement in our sin and suffering towards the triune God of scripture, for the sake of laying ourselves bare before him, that he might act in whatever way would give us his hope and life. This movement in practice can manifest in a variety of ways, some of which will be discussed later in the article. In the process, lament does not necessarily mean everything will work out to our satisfaction, but rather that a good and gracious God is still at work. To that end, it is helpful to think of lament in relation to the gospel. That is, to allow the gospel narrative to inform the laments in scripture and in our lives.

Lament in the Gospel

What is revealed in the gospel is the work of God, through chaos and death, to give us his life. The intervention of God, which is the hope of every Old Testament lament, ultimately comes by way of the suffering servant who is Christ Jesus (e.g. Is. 53; Lk. 24:13-27; Acts 8:26-35). Thus, the gospel embraces the depths of despair and helplessness yet gives us a vision and a promise of the resurrected life towards which those in union with Christ might move, even as we experience sin and suffering. If lament consists of movement towards God in word and deed, and not merely the lip-service we often give, then the gospel challenges us to reconsider what it might mean to live out lament beyond offering pause and prayer in difficult times. This movement is embodied in Christ.

As it concerns the person and work of Christ, the Exodus narrative is a helpful primer. In the Exodus event, God looked on the estate of Israel, heard their laments, their appeals for mercy and justice, and in response, sent a redeemer, Moses. In Hebrews 11:1-12:3, Moses, like many other Old Testament redeemers, is regarded as a forerunner and foreshadow of Christ. In other words, there is an anticipation of God’s saving presence all through the Old Testament. And each time God intervenes, the people of God are reminded that the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is not only the true God, but one who deeply cares for us.

In Christ, God does not simply send another redeemer. He sends his son, Jesus. The revelation and name of Jesus (“God with us”) reveals that Christ is not just another ministering spirit. He is not just a servant of the Lord. Rather, he is Lord and God (e.g. Matt. 1:21-23; Phil. 2:9-11). What is also revealed is that, in Christ, God is responding to our deepest pains and hurts. And man’s deepest lament is not against any skin color, nationality, or social injustice; but against the principalities and forces that work to keep men and women in bondage and separated from God; our true enemy as it were (Eph. 6:10-18).

Scripture discloses in various ways this enemy or unholy trinity. It speaks of our sin against God and one another, of Satan our adversary, and finally of death.7 Our sin puts us at enmity with each other, Satan is a deceiver and a murderer, and death is an end to life. This unholy trinity works towards one end: to defile and destroy. Further, outside of the grace and power of God to intervene, victory against sin, Satan, and death is impossible. While this enemy works to destroy God’s creation, the irony is that we in our sin and stubbornness are often willing collaborators in our destruction. The result is that we ourselves live more as enemies than as friends of God, more out of self-interest than love for others. This is evident in our relationships, communities, and systems. It is this grim reality that paved the way for Christ.

The laments in the Old Testament help us remember that behind every lament lies this issue: if God is unable to intervene, if he is unable to have the last word, then everything is ultimately in vain. Thanks be to God that at the cross he conquers sin, Satan, and death (Rom. 5:6-11; Rom. 6:8-11). In other words, God took the curse of death upon himself through his Son, and despite the sting of death, triumphed over it. While it will not be fully consummated until Christ returns, God’s victory over sin, Satan, and death is certain. His victory is both already and not-yet. That is, God’s victory in Christ is already a reality which can be experienced in part in the here and now and will be fully experienced by all those in Christ when he returns.

In 1 Corinthians 15, the apostle Paul reminds the people of God: “’Death has been swallowed up in victory.’ ‘Where, O death, is your victory? Where, O death, is your sting?’ The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.” The death and resurrection of Christ, then, is a declaration of God’s proclamation that sin, Satan, and death will not reign forever. Further, the resurrection reveals God’s ultimate answer to our laments, namely the life-giving power of his son.

Finally, although Christ physically departed, he also left his Holy Spirit, so that as we continue to endure hardship and suffering in this life and await his return, we can know with confidence that Christ is in us, with us, and will never leave us. In fact, his Spirit convicts and assures us that we are seated with him at the right hand of God the Father even now.8 The presence of the Holy Spirit reminds the people of God of at least two things: we can lament with hope while sin and death remain; and, there will one day be an end to lament when sin and death will be no more at the return of Christ.

By the Holy Spirit, we can have confidence that Christ’s presence and peace is more powerful than our conflicts and struggles. We can have confidence that our laments need not be isolated stories but joined to his gospel. Further, we can have confidence that hope has been perfectly embodied in Christ who will one day return. As a result, we as the people of God can lament with hope as we live in and mine the depths of the gospel of Christ.

Indeed, there is an intimate relationship between lament and the gospel. In a sense, the two are inseparable. Lament is an honest naming and acknowledgement of sin and suffering with intentional movement towards God; the gospel is the story of God entering into our sin and suffering to lead us to himself through Christ. Approaching lament, then, with more attention to its relation to the gospel has the potential to encourage evangelical churches towards new paradigms and habits.

Four Practices to Bridge Lament and Discipleship

Four practices will be considered in view of how we might embody lament after Christ, based on scripture and my years in ministry as an Assistant / Outreach Pastor in and nearby the Philadelphia area. These practices are: listen, look, lament, and limp. Consider briefly the following ways these steps were on display in Christ. He listened and engaged our narratives; he looked and addressed issues of sin and suffering, both surface and underlying; he lamented, in that even as he took on our sorrows, he still moved towards and entrusted all of it to his heavenly father; and he limped, in that he suffered with and for us to the point of bearing nail-pierced hands and feet for eternity.

It is important to note that these steps are not an exhaustive list. There are numerous other practices that can be tied to lament. These four steps need not be rigidly implemented in a linear fashion or with equal measure; it is likely that they will be applied non-linearly and in a combination of ways befitting the context. However, my hope is that as these steps have challenged other congregations towards lament, they might also be a means of strategically, intentionally, and humbly keeping each of us alert to our context and to the movement of the Holy Spirit as we learn to embody lament.

Listen

The first practice is listening. Listening well is difficult. It requires patience and effort, and it will require asking questions to better understand the context. This task is more difficult given that we listen best to what we want to hear, or to that which arises from shared convictions. James 1:19 speaks to this struggle to truly hear one another: “You must understand this, my beloved: let everyone be quick to listen, slow to speak, slow to anger.”

Listening will also cost you. It will not merely cost you time and energy, but loss of power. However long that moment might last, the one listening has in effect yielded to the one speaking. And if they are listening well, their mind is not elsewhere, but attentive to the other. In some cases, value and worth are ascribed to the speaker. For example, it is always fascinating to see the panel of speakers that have been selected at any given conference. The panel lineup tends to communicate at least two messages: it reflects who the conference values as well as what ideas and stories it has deemed worthy of your time.

Listening will cost you. It will not merely cost you time and energy, but loss of power.

It is quite amazing, then, to see the list of people whom Christ valued and esteemed simply by listening and engaging their stories. This list included the powerful and the powerless, rich and poor, religious and irreligious. The following is only a sample of intimate encounters in which Christ listened and engaged: a desperate mother (Matthew 15:21-28); a rich young man (Matthew 19:16-30); a blind homeless man (Mark 10:46-52); a respected religious leader (John 3:1-21); a despised promiscuous woman (John 4:1-45); and lastly, a stubborn and assorted group of twelve disciples whose interactions with Jesus are found throughout the Gospels.

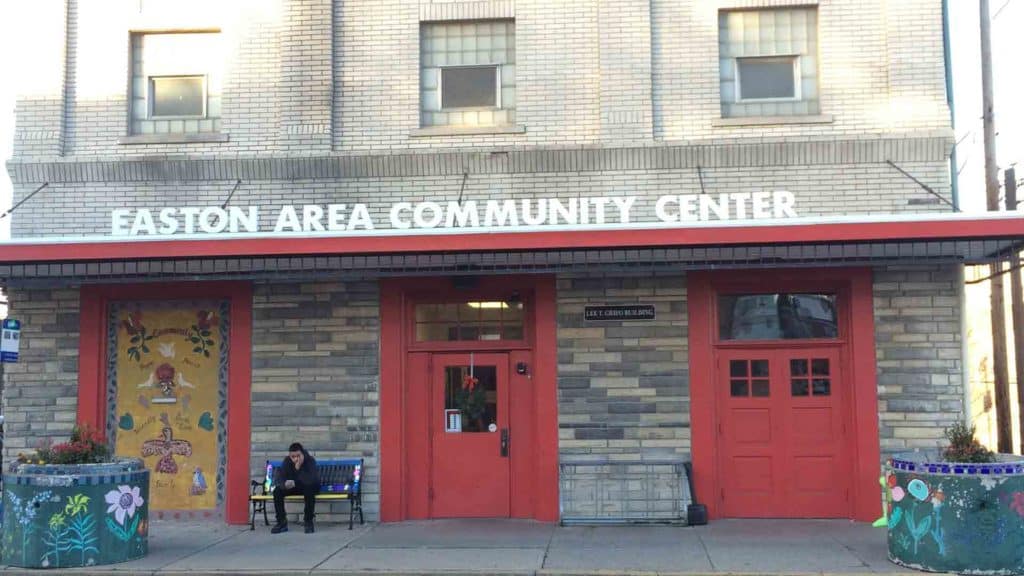

As a pastor who formerly facilitated discipleship in house churches, I have experienced the positive effects of a house church filled with members willing to listen to one another and the negative effects when emotions are high and listening proves difficult. One case in particular exposed the thorns and the fruit that can accompany efforts to develop a listening culture.

This case involved Shirley, an older white woman in her seventies who lived alone with her two cats and moved around often. Shirley had a lively spirit and always seemed to know what was going on in the city, especially regarding local high school sports. However, from the moment she first walked into our house church (which at the time was meeting in a local community center), it was clear that she had a lot on her mind, and much to say to anyone willing to listen. As such, she would regularly interrupt people or unknowingly monopolize the discussions. This frustrated members in the house church, and even caused a few to stop attending. However, as the group set time to listen and lament with her, she increasingly began to interrupt less and listened to others more. It was almost as if she needed to go through a season of an emotional and verbal catharsis first before she could begin to feel less fearful and more trusting of God and others.

Listening well might be the simplest and most demanding of the four practices. In theory, it requires very little from us. Yet, as was the case with Shirley, it brings you to the end of yourself. In addition, it requires being led (as the person brings you into their story and context) rather than you leading the person’s story. Having worked with several senior pastors through the years, in suburban and urban contexts, I have discovered that senior pastors can have the toughest time listening to others, even though ironically many are serving their people all the time. The reason is, to listen well is to invite others to impact you, potentially resulting in significant changes to how you live, think, and relate to others.

We always have to do something with the news and stories that come our way. Even if our response is no action, it never leaves us as we were. Listening well creates space to hear encouraging and discouraging news, constructive and destructive criticisms, sad and happy stories, uplifting and hurtful messages. Given the influence of the senior pastor(s) on the life of a church and its members, they are often the one whose voice impacts others, and not the other way around. Thus, for the senior pastor(s) to invite the congregation and the community to impact them and change their lives, thoughts, and relationships can be a terrifying experience for some pastors.

For those of us who are change agents, moving towards healing and reconciliation is nearly impossible if we do not do the hard work of listening, especially in seasons of racial, social, and political tension. Cultural anthropologists, Branson and Martinez, give one example of how this practice might impact a church,

We need to listen to each other’s narratives because these “are the cultural framework in which individuals interpret their social situations, imagine themselves in other situations, and make choices about who they want to be and how to behave.” By inviting church members to tell their cultural narratives and to listen to those of others we expand our understanding of each other and of how we see ourselves in the world. Learning how to tell my own cultural story and how to listen to others’ narratives gives a very important message within the life of a church. On the one hand it makes me think about how I “imagine myself.” But it also says that all members are important in a congregation’s broader story.9

Thus, through corporate rhythms of creating space to listen to each other’s stories, especially to members of the marginalized members in our communities, congregations can practice honoring their fellow brothers and sisters by entering into their stories, listening to different perspectives, and tangibly reminding one another that our following of Christ is not an individual endeavor, but a communal one.

Look

The second practice is looking. Looking is a two-fold exercise. It involves seeing what is visible and invisible. As it concerns the former, looking is about seeing and processing the obvious details. While this may sound easy and effortless, it also requires attention. Curt Thompson, psychiatrist and author who emphasizes the connection between neurobiology and spiritual formation, builds further on this concept,

It only makes sense that our lives are affected by what we pay attention to, and if we don’t pay attention, we are likely to have problems. If you don’t pay attention to the pedestrian in the crosswalk, you may run him over. Simple enough. But despite the fact that we believe that paying attention is important, the truth is we live much of our lives inattentively.10

In other words, our version of looking tends to consist of paying attention to what we want to see rather than to the context. In the process, we forfeit opportunities to grow in understanding of each other. News outlets are a great example of selective looking. Networks shows us what they want us to see, and in return we receive and reiterate that message to others. This over-dependence on the pictures and presentations of selective news outlets has been one of the greatest barriers, since the latter half of the twentieth century, towards attempts to patiently and sincerely engage others with different opinions and viewpoints.

In the life of the church, selective looking can manifest as never asking “outsiders” for help. In fact, one of the most dangerous and proud assumptions a congregation or leadership team can make is to figure things out on their own, and in isolation from other churches and non-profits. As the body of Christ, there is an innumerable measure of gifts, talents, and resources available to the church. Ephesians 4 and 1 Corinthians 12 are reminders of the work of the Spirit in the church. However, these passages also remind us of our need for one another, locally and abroad. No one congregation or leader has a monopoly on the gifts of the Holy Spirit. We all have our blind spots and biases, and could use another set of eyes, not only from quarterly/annual denominational meetings, but from community developers, spiritual directors, and other gospel-centered practitioners, to help us see what might be obvious but hidden to us.

Selective looking can manifest as never asking “outsiders” for help. In fact, one of the most dangerous and proud assumptions a congregation or leadership can make is to figure things out on their own, in isolation.

While many congregations would agree in theory with the statements above, most tend to functionally assume the position of helping others rather than receiving help, of being the discipler rather than the one being discipled. This posture is especially harmful to building Christian ministries that are multicultural, as our cultural presuppositions can often be patronizingly projected onto others as the right or best foundation on which to grow in the Christian faith.

Looking is also about seeing beyond what is visible and seeing the underlying realities at work. This is the more difficult, and less practiced, form of looking because it requires wisdom, humility, and curiosity. It requires being open to having your interpretation of events corrected and expanded. As a result, we often neglect this exercise, or yield only to the interpretations of the experts in our tribe. Given our biases, there is vigilance required on our part as we attend to multiple perspectives on a given situation.

There are numerous cases in the Gospels in which Christ sees scenes differently or beyond what the crowds and disciples see. Here is one example. In Luke 7:36-50, Luke describes a scene in which Jesus’s feet are being washed and anointed by a sinful woman, likely a prostitute. While the guests and disciples see an uncomfortable scene unfold, and even silently rebuke Jesus for allowing it, he sees a woman, hurting and looking for someone to take away her guilt and shame. As he looks at her, he offers these words to those listening,

Then turning toward the woman, he said to Simon [the host], “Do you see this woman? I entered your house; you gave me no water for my feet, but she has bathed my feet with her tears and dried them with her hair. You gave me no kiss, but from the time I came in she has not stopped kissing my feet. You did not anoint my head with oil, but she has anointed my feet with ointment. Therefore, I tell you, her sins, which were many, have been forgiven; hence she has shown great love. But the one to whom little is forgiven, loves little.” Then he said to her, “Your sins are forgiven.” But those who were at the table with him began to say among themselves, “Who is this who even forgives sins?” And he said to the woman, “Your faith has saved you; go in peace.”

Christ looked at her and not only addressed her guilt and shame but restored her dignity and worth. It was an uncomfortable situation. Jesus’ reputation was being questioned, so too the reputation of his disciples. Yet he looked at her and engaged her with compassion. Moreover, he encouraged his disciples to do the same.

Lament

The third practice is lamenting. As explained earlier in this article, lament is more than a prayer, though it can certainly take that form. But lament is also movement, in word and deed, with our heart, mind, and bodies, towards God in the face of sin and suffering. Among other activities, this movement can include (though not be limited to) praying, singing, crying, silence, contemplating, and confronting. In other words, biblical lament cannot, nor should it be, reduced to one activity. The core objective might be the same (i.e., reaching out to God in the face of hardship), but how it manifests varies. For example, one form of lament could be naming and speaking honestly on systemic abuses in and outside the church. Seth Richardson argues,

Without the ability to name and critically engage the larger stories, histories, and social forces shaping a community, spiritual awareness can be limited by the echo chambers of individual experience, and communal discernment can be short-circuited by the personal whims and pathologies of a solitary leader or dominated by the loudest voices. In other words, it’s possible to dig into personal issues yet remain unaware of the most significant dynamics shaping us. It’s possible to have visionary leadership yet remain lodged in unhealthy, de-formative habits.11

The practice of naming and acknowledging the forces that overwhelm us is a form of lament, as it moves individuals and congregations to struggle honestly with God and one another regarding the social and spiritual forces at work that disorient our lives and to inquire what God might have us do in response.

Similarly, authors Billman and Migliore contend that, “…one of the important ministries of Christian congregations is to provide a place and a language to give voice to suffering. The prayer of lament provides an irreplaceable language of pain.”12 While laments in the Old Testament, especially in the Psalms, showcase examples of questioning, complaining, and/or pleading with God in times of anguish and hardship (e.g. Ps. 10, 35, 44, 80, 102), it is important to remember that they are ultimately forms of movement towards God in our suffering, not only with our words, but with our whole selves.

In addition, one of the principal takeaways from the laments in scripture is that lament and intimacy with God are impossible to separate. One could say that biblical lament is intimacy with God forged in suffering. Since pain and suffering abound, there are ongoing moments to wrestle with God, individually and corporately. This will require not turning from or overlooking our pain and suffering nor avoiding delicate social issues as can be the case in many churches. Rather, it is an opportunity to intentionally acknowledge and address our sins and struggles before God and one another.

Lament is intimacy with God forged in suffering.

Closely related to my former work with house churches was the opportunity to guest facilitate a social justice event for a predominantly white congregation. This was a three-part event that provided opportunity for that particular church and its local community to wrestle corporately through social issues related to racism and prejudice. The events were well attended, with about 75-100 attendees at each forum, including several members of the church’s leadership team. The audience was lively and willing to engage. Further, there was constant support shown to those who shared their stories, through applause, tears, and silent acknowledgment. Moreover, the sense of community and togetherness was evident as the attendees connected and continued the discussions afterwards with a meal provided at the church.

However, the impact of the event was short-lived in the life of that church, as this event took place in the context of the church’s mercy ministry to the poor and homeless. That is, it was more so a ministry event for “others,” and less so for the congregation. I recall one of the attendees from the community asking me after an event, “where are all the church members?” This observation reflected an all too common reality. That is, when lamenting becomes something we only see as valuable for other people and not for ourselves and our congregations, we will tend to avoid speaking into the issues of our day that are hurting and dividing our congregations and communities, and we will miss opportunities to see what God might do in the midst of those moments.

Limp

The fourth practice is limping. Limping is not often thought of as a worthwhile and productive activity. For many, it is a less than ideal situation, perhaps even the result of a failed and cursed life. Yet, in scripture, there is more grace to be found in weakness than strength. One of the clearest examples to illuminate the grace that can be found in limping is the story of Jacob and his encounter with God.

In Genesis 32, the writer describes a scene in which Jacob is waiting anxiously and fearfully for his brother Esau, whom he had wronged many years prior by stealing his birthright. Jacob expects the worst. As he waits in trepidation, he is visited by an angel of the Lord who proceeds to wrestle with him all night and into the morning. Unable to overpower Jacob, the angel dislocates Jacob’s hip so that he is left limping. However, Jacob refuses to cease wrestling until the angel of the Lord blesses him. In response, the angel blesses him by giving him a new name and a new narrative, no longer to be known as Jacob, the one who deceives, but as Israel, the one who wrestles with God. Although Jacob’s wrestling with God resulted in limping, it also led to blessing.

Not every act of wrestling with God results in the dislocation of our hips. However, limping is an apt picture of our encounters with struggle and hardship. No one who experiences suffering is left unaffected and unscathed. It causes us to readjust our posture and perspective towards God and others. Limping, then, is a nagging reminder that creation is still groaning and waiting to be fully healed. Laments are the voices of those who limp before the Lord, who have encountered pain in one form or another, and who are moving towards the only one who is the giver and sustainer of life.

No one who experiences suffering is left unaffected and unscathed. It causes us to readjust our posture and perspective towards God and others. It causes us to limp, and enter into struggles of others.

To limp with others, then, is to bear each other’s burdens, and to enter each other’s struggles, because of the hope we have in Christ. This will potentially disrupt and disorient our schedules and plans, even our dreams. However, it will also lead to opportunities to trust in and embrace a big God who is able to do far more than what we could dream or imagine (Eph. 3:14-21). Such opportunities can manifest in numerous ways, including meeting physical and financial needs, providing accountability and hospitality, steadfast prayer, and being present with those going through tough times.

One example of limping involved a church member named Pete. Pete is an African American in his late thirties, single, and with little income. His daily battle was to find a steady job and not live on the streets. Since there were few close family members nearby, this became an increasingly difficult, almost hopeless task. Pete often had to find housing at a local shelter for lack of finances and relational network. This pattern changed when a member of the house church, who had previously befriended Pete, introduced him to the house church.

From that meeting, friendship slowly developed with other members of the house church. Pete eventually began attending more regularly. As he shared his story and struggles, members of the house church would limp alongside him in various ways. This included helping him with job searches and resume building, finding a steady job, finding a place to live, regular invitations to various member’s homes for lunch and/or dinner, and constant prayer and encouragement. In the process and over a few years, Pete not only matured in his faith and character but served as a testimony to the entire church community.

By sharing life with Pete, the church also intentionally shared in his hardship. Glen Pemberton offers this encouragement to those who would limp with others and share their scars,

Faith does not require us to ignore the scars from our losses; even the resurrected Christ still had his wounds. Nor does faith promise memory erasure so that we can live and act as if nothing happened. Something has happened – death in all its forms: abuse, pain, grief, rape, aggression, divorce. Nonetheless, in the rhythm of resurrection, God’s work in our lives becomes part of our faith story and integral to our new language of thanksgiving.13

Conclusion

We are given daily opportunities to know Christ and others more fully as we listen, look, lament, and limp as we die to ourselves, and yet in some mysterious way, live in the rhythm of resurrection. Like a narrow gate, biblical lament is hard to engage, but it is also part of our following of Christ. Lament is never severed from discipleship, and we neglect it to our detriment. However much a congregation might desire to be biblical and Christ-centered, every church and leadership have decisions to make about what to prioritize and what to pursue. Are we incorporating lament in our households, churches, and communities? Is lament part of the vision and mission of our church? How have / might the four practices—listen, look, lament, limp—manifest in our congregations and in our lives?

Dan Allender once observed,

Many individuals know deep suffering. But few have been part of a culture that is defined by sorrow. If one reads, or listens to the art of these cultures, one is led not to despair, but to passionate hope. It is far from what we expect. But I would argue the greatest power in art, life, and faith comes from the soil of lament. Lament embodies the passions of need, the fight against injustice, and implicitly the loudest proclamation of hope.14

A life and ministry that is informed by biblical lament need not be one of gloom and doom. Although there is much to lament in this world, there is also much hope to be found.

Notes

1 Matthew 7:13-14. Unless otherwise noted, all biblical passages referenced are in the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV).

2 Similar verses can be found in Luke 13:22-30, albeit this time to both the disciples and the crowds.

3 Walter Brueggemann, The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House, 1984); Walter Brueggemann, “The Costly Loss of Lament,” in Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, vol. 11, issue 36 (October 1, 1986); Walter Brueggemann, edited by Patrick D. Miller, The Psalms and the Life of Faith (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995).

4 See Soong-Chan Rah, Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2015); Mark Vroegop, Dark Clouds, Deep Mercy: Discovering the Grace of Lament (Wheaton: Crossway, 2019).

5 Claus Westermann, trans. Richard N. Soulen, “The Role of the Lament in the Theology of the Old Testament,” in Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology, vol. 28, issue 1 (January 1, 1974), 25.

6 Scott Ellington, Risking the Truth: Reshaping the World through Prayers of Lament (Eugene: Pickwick Publications, 2008), 30.

7 Genesis 3:1-5; John 8:42-44; Romans 7:7-25; I Corinthians 15:24-28; Ephesians 6:10-20; James 4:1-12; I Peter 5:8-9; I John 3:4-8; Revelation 20:1-6.

8 Galatians 4:4-7; Colossians 3:1-4; Romans 8.

9 Mark Lau Branson and Juan F. Martinez, Churches, Cultures, and Leadership: A Practical Theology of Congregations and Ethnicities (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2011), 235.

10 Curt Thompson, Anatomy of the Soul: Surprising Connections Between Neuroscience and Spiritual Practices That Can Transform Your Life and Relationships (Carol Stream: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2010), 53.

11 Seth Richardson, “The Most Important Pastoral Practice for Our Time,” Missio Alliance (blog), February 3, 2017, https://www.missioalliance.org/important-pastoral-practice-time/.

12 Kathleen D. Billman and Daniel L. Migliore, Rachel’s Cry: Prayer of Lament and Rebirth of Hope (Cleveland: United Church Press, 1999), 106.

13 Glenn Pemberton, Hurting with God: Learning to Lament with the Psalms (Abilene: ACU Press, 2012), 178.

14 Dan Allender, “The Hidden Hope in Lament,” The Allender Center at the Seattle School (blog), June 2, 2016, https://theallendercenter.org/2016/06/hidden-hope-lament/.

Works Cited

Allender, Dan. “The Hidden Hope in Lament.” The Allender Center at the Seattle School (blog). June 2, 2016. https://theallendercenter.org/2016/06/hidden-hope-lament/.

Billman, Kathleen D. and Daniel Migliore. Rachel’s Cry: Prayer of Lament and

Rebirth of Hope. Cleveland, OH: United Church Press, 1999.

Branson, Mark Lau and Juan F. Martinez. Churches, Cultures, and Leadership: A

Practical Theology of Congregations and Ethnicities. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2011.

Brueggemann, Walter. The Message of the Psalms: A Theological Commentary.

Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Publishing House, 1984.

Brueggemann, Walter. “The Costly Loss of Lament.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, vol. 11, issue 36 (October 1, 1986).

Brueggemann, Walter. Edited by Patrick D, Miller. The Psalms and the Life of Faith. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1995.

Ellington, Scott. Risking the Truth: Reshaping the World through Prayers of Lament. Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2008.

Pemberton, Glenn. Hurting with God: Learning to Lament with the Psalms. Abilene, TX: ACU Press, 2012.

Rah, Soong-Chan. Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times. Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2015.

Richardson, Seth. “The Most Important Pastoral Practice for Our Time.” Missio Alliance (blog), February 3, 2017. https://www.missioalliance.org/important-pastoral-practice-time/.

Thompson, Curt. Anatomy of the Soul: Surprising Connections Between Neuroscience and Spiritual Practices That Can Transform Your Life and Relationships. Carol Stream, IL: Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., 2010.

Vroegop, Mark. Dark Clouds, Deep Mercy: Discovering the Grace of Lament. Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019.

Westermann, Claus. Translated by Richard N. Soulen. “The Role of the Lament in the Theology of the Old Testament.” Interpretation: A Journal of Bible and Theology, vol. 28, issue 1 (January 1, 1974): 22.

1 thought on “Taking the Narrow Gate: How Lament Shapes Multicultural Ministry and Discipleship”

Hello, Sahr Mbriwa, this is such a profound and moving article. I want to thank you so much for expressing this topic so well. My role includes helping multi-ethnic churches move towards intercultural worship. My current premise is that it must start with listening well (deeply, humbly, compassionately, etc.), hearing one another’s stories and expressions of faith and move to collaborative experimentation in which all are free to innovate together. Your insights about the four practices are so, so helpful!!