Behold, children are a gift from the LORD; they are a reward from him. (Proverbs 127:3, NIV)

Two 17-year-old youth, arguing. A crime is committed. The outcome? It depends…

True Story

Two 17-year-old African American youth live in a low-wealth, resilient, urban community frequented by trauma. They play ball together in the gym of a congregation around the corner. They’ve known each other all their lives; they grew up together. They’re friends. They’re talking to a girl. The same girl! This particular night, one makes a phone call to his girl. The other is actually visiting her, on a date. One comes to the other’s porch. An argument ensues. Teens flock to the scene. Expletives fly. Fists swing. The gun. The back of the gun. The head. The ambulance. The stitches. The… felony? The cop. The pastor. The talk. The restorative practice. The law. Do it anyway. The restoration. The wholeness. The friends. The diplomas. The next girlfriends. The babies born. The birthdays celebrated. Back to the gym. Together, playing ball – with their kids. The end. Happy. Whole.

The outcome should have been, by sentencing guidelines for the state, a felony weapons offense. Since the person with the gun had a juvenile record and was a few months shy of his 18th birthday, he likely would have been tried as an adult. His sentence would have been imprisonment. His life, and that of his community and family, would have been immeasurably altered for the worse. Thank God, an alternative course of action was decided by a few brave people, including the police officer and his captain.

These children’s lives and communities were changed for the good of humanity because they leveraged an ancient village process now formally called restorative conferencing.

A restorative conference is a structured meeting between offenders, victims, and each party’s family and friends, in which they deal with the consequences of the crime or wrongdoing and decide how best to repair the harm. This method allows citizens to resolve their own problems when provided a constructive forum to do so.1 The conference referred to above involved a cop with a title, “community-relations officer,” who took a chance on relationships built over a few years with a community. The officer had to face a newly implemented progressive legal process that allowed community involvement, at the precinct level, when a crime was committed – as long as it was non-violent. Otherwise, this crime would have been adjudicated as a violent felony.

Trust entered the story early, thank God. Trust is a necessary component toward executing any successful restorative practice session, which allows citizens to resolve their own problems within a constructive forum.

The children involved (yes, a 17-year-old remains a child), the police officer, and the pastor knew these young people, or their loved ones would not have gone to the precinct. Did I tell you one of the young people was homeless at the time? The officer worked together with the community on adjusted protocol. Trust entered the story early, thank God. Trust is a necessary component toward executing any successful restorative practice session.

The other necessity is that the victim and the offender want to make things right. In this case, the teens recognized that the argument had gotten out of control. They recognized that a felony had been committed. They recognized each other’s pain. They recognized and valued their relationship. Therefore, they agreed to work together to achieve mutual wholeness.

In the beginning, even with angry feelings, they signed an agreement to an unfamiliar process. They also agreed that neither one would quit the process prior to completion. At the time of the first session (there were four), everyone maintained self-imposed “social distancing.” Accompanying each young person were their “relations,” chosen by each child (not necessarily parents). These people were prepared before each session to participate in the process. The pastor and the officer were also present, as well as friends who had witnessed the event.

After the four facilitated conversations ending in repentance by each teen, a settlement was reached. This fight harmed many: two teens, two groups of relations, one community, one officer, one church, one precinct.. The settlement, determined by persons harmed and their communities, included:

- Six months of school attendance, every day all day

- Six months of community service at the gym

- 1 new pair of sneakers

- $50 for suffering

The outcome? Hugs, tears, laughter, relief, new and renewed friendships, thanksgiving for a future with continued hope. Everybody graduated high school. Every family remained intact. Every life was lived.

The challenge is that not enough people know about restorative possibilities, and some of those who do know do not trust such soft-on-crime solutions.

There are more true stories from this community where restorative justice became a way of life mediated by a church, a precinct, and neighbors. We learned a lot about the power people have to determine their own legal recourse when there is trust between people and between systems. People sometimes break and bend the law to cause harm; but we learned that just people within community and government systems can stretch and bend laws to facilitate wholeness. The challenge is that not enough people know about these possibilities, and some of those who do know do not trust such soft-on-crime solutions, even if they are permitted in their legal jurisdictions.

This accessible, yet often untapped, resource that moves our communities away from state-run systems of retribution–adjudication, policing, and incarceration–toward neighbor-led systems of restorative justice is possible in most states in America.

There is another resource that uniquely involves the 77% of persons in the United States who share a common value system–the Christian community in mission.

Jesus replied, “Love the Lord your God with all of your heart, and with all your soul, and with all of your mind. This is the first and greatest commandment, and the second is like unto it. Love your neighbor as yourself” (Matthew 22: 37-39b NIV).

Restorative practices align with these critically important and mandated commandments.

Since an overwhelming majority of Americans confess Christianity (among them 88% of the nation’s Congress who create, implement, and oversee U.S. judicial policies), perhaps we can find a way to live into Jesus’ command to actively and bravely love. We also have a road map – 2 Corinthians 5:18, “All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ and gave us the ministry of reconciliation.”

The Challenge

Christianity remains the primary faith of the majority of the people both in the U.S. and in nine out of ten of the industrialized nations. Yet these industrialized nations, compared to the non-industrialized nations, imprison the largest percentage of their children under 18 years of age.2 Conversely, the non-industrialized countries, including those in Africa, Asia, Oceania, the Caribbean, the Pacific Islands, and the Aboriginal communities of Australia and the American Indian/Indian Native (AI/AN) nations of North America have displayed restorative practices centered in community and family for millennia.

The outcome of this is that these non-industrialized countries incarcerate substantially fewer young people under 18 than the “industrialized” nations. And all countries incarcerate fewer children than the U.S. It is a fact that the so-called non-industrialized nations surpass the industrialized nations in adhering to the United Nations’ guidelines by permitting children’s families and communities to resolve harmful incidents in light of a child’s reported desperate and/or delinquent activity(s), thereby protecting children from additional and protracted trauma.

The outcome of current practices is that these non-industrialized countries incarcerate substantially fewer young people under 18 than the “industrialized” nations. And all countries incarcerate fewer children than the U.S.

In contrast, see the declaration from United Nations:

Article 27 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) affords every child the right to a standard of living adequate for the child’s physical, mental, spiritual, moral and social development… The CRC stipulates that states’ parties are responsible for enuring such care in situations where children are temporarily or permanently deprived of his or her family environment.3

The prophet Micah offers a reflection on God’s rhetorical response to the question the Hebrew nation tended to always ask God, “Lord, what do you require of us?” God’s response is found succinctly, in Micah, “And, what does the Lord require of you? To act justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with your God” Micah 6:8b (NIV).

The 2007 Bible Study, developed by Prison Fellowship International’s Center for Justice and Reconciliation, notes that very often justice and love are understood as distinct, and are seen as opposing values and aims. On the one hand, justice is commonly depicted as harsh judgement, as punishment without mercy. On the other hand, love is perceived as sentimentality where wrongdoing is simply overlooked without consequence.4 The study goes on to point out that justice and love are both part of the very character of God, the Righteous Judge. The Scripture as a whole remains a living testament of God’s demonstration to us throughout time, of a people reconciled to God and to each other. We have the example of Jesus and the powerful indwelling of the Holy Spirit to assist us in this lifelong journey toward reconciliation inclusive of humanity’s treasure, our children.

Since we American Christians incarcerated so many of our world’s youth, we must ask three critical questions:

- Why have the followers of Jesus in the U.S. neglected children’s safety by straying from a faith proclaiming reconciliation and life grounded in love, to embracing a “faith” of retribution and death, grounded in punishment?

- How did our country’s culture and history contribute to our appalling world-wide leadership as the number one incarcerator of children?

- How can we reclaim our children and our humanity by actively repenting and implementing proven strategies already in use by two-thirds of the world, strategies that could reverse this negative trajectory of child abuse and child endangerment at the hands of our state’s criminal systems?

Some Facts

The United Nations Children’s Fund, UNICEF, has estimated that more than 1 million children are behind bars around the world. Many are held in decrepit, abusive, and demeaning conditions, deprived of education, access to meaningful activities, and regular contact with the outside world.5

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the United States still incarcerates more young people than any other country, with over 48,000 children in confinement on any given day. And tragically, in any given year over 500,000 youth are cruelly traumatized by being adjudicated into detention centers.6 The ACLU also reports that “most [U.S.] states continue to use an outdated and harmful ‘training school’ model, confining children in remote, prison-like facilities cut off from their families and communities.”7 An article in the Journal of Child Abuse & Neglect makes the following conclusion:

…a country’s or region’s history of care provision is likely to have shaped its current child welfare systems, and to have influenced societal perspectives and beliefs about the care and protection of children.8

Sadly, there are numerous conditions under which children might find themselves deprived of their family’s household (i.e., parental death, parents inability to provide sustenance, shelter, or protection, war-time separation and/or displacement, state intervention for a number of reasons that vary by country, e.g., truancy, suspected- or actual- criminal activity, sex-work, pregnancy, domestic violence, substance abuse, and homelessness). Many, if not most, of these offenses can find themselves related to the sin in the fabric of historic structures of the country–demonic claims of racial superiority which gave permission to claims of “manifest destiny,” a mid-18th century belief that it was the divinely ordained right of the U.S. to expand its borders to the Pacific and beyond. First they were to expand through continental acquisition of lands from the First Nations as well as to justify the removal and purchase of human property from Africa. It was the destiny of white European America, as God’s special people, to attain land and property in the name of their God. This concept was justified, sadly, through the misreading of Old Testament scriptures lending themselves to propagating the myth of a God-ordained right to the conquest and annihilation of people, culture, and homeland.

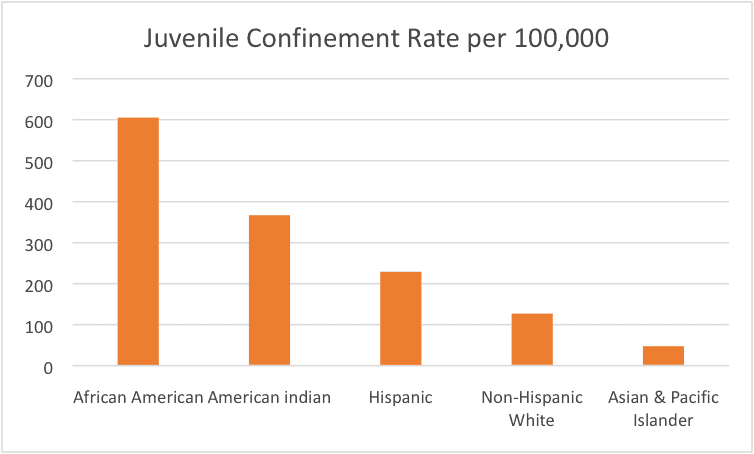

In the U.S. the particular minority people displaced from land and culture have become the majority residents of the juvenile (and adult) penal systems–American Indians and African Americans. “For centuries there have been grossly disproportionate incarceration of children from these two ethnic people groups.”9

Black and American Indian youth are over-represented in juvenile facilities, while white youth are underrepresented. Sadly, and uniquely, the incarceration rate of American Indian youth is 38% higher than Whites in local, state and local run facilities, and a whopping 70% higher White youth in federally run facilities. The increase in youth incarcerated in federal facilities is linked to Indian-Country federally enforced US adjudication policy.10

Racial disparities are also evident in decisions to transfer youth from juvenile to adult court. Although the total number of youth judicially transferred in 2017 was less than half what it was in 2005, the racial disproportionality among these transfers has actually increased over time. …The type of facility where children are confined can affect their health, safety, access to services, and outcomes upon re-entry. … More than 9500 youth in juvenile facilities – or 1 in 5 – haven’t even been found guilty or delinquent, and are locked up before a hearing (awaiting trial). Another 6,100 are detained awaiting disposition (sentencing) or placement.11

This cruel punishment of our young people remains ungodly and far from the strict command of our Lord and our God to love one another found in our gospels of liberation.

In light of these facts, let’s address the questions we have posed above.

- Why have the followers of Jesus in the U.S. neglected children’s safety by straying from a faith proclaiming reconciliation and life, grounded in love, to embracing a “faith” of retribution and death, grounded in punishment?

Sadly, we as a nation have not healed from the wounds of genocidal racism, especially as it relates to its American Indian and African American neighbors. We sadly may not even consider our children, individually or collectively, as neighbors. Therefore, our youngest neighbors often remain outside of the Christian community’s formal (in churches and seminaries) or informal dialogues related to ending mass incarceration. Additionally, whether discussing youth or adults, our culturally dehumanizing biases against certain ethnic groups, certain crimes, or certain accusations cause many Americans to favor punitive and retributive philosophy of punishment, rather than embracing the empowering and reconciling philosophy of a loving justice system for our children.

These biases also prevent us from accepting non-western strategies and tactics proven to be successful by the two-thirds world. These strategies, collectively termed restorative practices, have been in use for centuries by the majority of the world’s cultures. They are pre-state tactics used to resolve underlying conflict and to determine a mutually agreed upon resolution between involved parties and between communities. Restorative justice has its roots in tribal reconciliation. From a biblical perspective, the ancient Hebrew view of justice includes the word shillum (restitution). This term originates from the same root as shalom. Mulligan concludes that “this linguistic link supports the notion that the aim of ancient Hebrew justice was to restore peace by restoring wholeness.”12

Culturally dehumanizing biases against certain ethnic groups, certain crimes, or certain accusations cause many Americans to favor punitive and retributive philosophy of punishment, rather than embracing the empowering and reconciling philosophy of a loving justice system for our children. These biases also prevent us from accepting non-western strategies and tactics proven to be successful by the two-thirds world.

Restorative practice views crime as an offense against another person versus the retributive justice model that views crime as an offense against the state. The restorative justice model sees the people involved, both victim and offender, as the same community and family. The restorative paradigm focuses not on the state but on two people (or tribes, or families, etc.) with the goal of actually repairing the harm done, thereby creating a path for the victim to achieve wholeness. It also seeks repentance and admission of responsibility from the offender through dialogue with parties involved, facilitated by a respected leader/facilitator from the community. For Christians this model resonates with Matthew 16:15ff (NIV): “If your brother or sister offends you, go and point out their fault, just between the two of you…. But if they don’t listen, take one or two others along…. If they still refuse to listen, tell it to the church…” and so on. In restorative justice the offender is required to admit responsibility for the harm before any such dialogue or negotiation can begin. Some scholars believe that the restorative justice model has been the dominant model of criminal justice throughout most of human history for all of the world’s peoples.13

- How did our country’s culture and history contribute to our appalling world-wide leadership as the number one incarcerator of children?

I wonder if ideas like Manifest Destiny, the “curse of Ham,” and other expressions of racist and divinely entitled attitudes of conquest of land and peoples directly contributed to the disproportional outcomes seen today in our criminal policy-making and our state-run criminal systems of adjudication. So many biblical texts of conquest and genocide in the name of God have been used to support “crusades” for over 4,000 years. Texts and sermons preached, even by “missionaries,” have supported the state-fostered agenda to annihilate individuals and cultures, to support the agenda of the divinely “chosen” country or ethnic group. In order for this rhetoric to take root in the heart of the citizenry, the state’s victims of all ages, it requires dehumanization.

During our history, fueled by these principles of racist superiority and entitlement, these processes denigrated any conquered inhabitant, child-adult-elder, to a status of less than human, less than neighbor, and undeserving of love. This mind-game became inherent in U.S. culture and created a purportedly non-human class of conquered American Indians and African Americans, outside of the human family and outside of the community. This removal of peoplehood effectively destroyed any potential path toward reconciliation of peoples and wholeness. “They” became, therefore, less than children of God. As these feelings are inculcated into civil law and practice, they are very hard to undo.

- How can we reclaim our children and our humanity by actively repenting and implementing proven strategies and tactics designed to reverse this negative trajectory of child abuse and child endangerment at the hands of the state’s system of incarceration?

We can repent of our xenophobia and racism and seek God’s forgiveness and direction to examine our motives and our attachment to destructive policies, proven to destroy children and their families. We can determine to stand in solidarity with the two-thirds world, and begin to reclaim our own biblical and historical culture of recognizing the humanity of others. This activity could lead toward natural reconciliation strategies, grounded in love, that acknowledge personhood and are grounded in community. We could “see restorative justice as a prominent method of conflict resolution and recognize that disparate cultures across the globe contemporarily utilize restitution as an effective method of problem-solving and restoring community peace following most violations.”14

Sobering Reminder

Lest we overly romanticize restorative practices, methods of punishment in the world today and in the ancient world were fraught with brutal, oppressive, genocidal, and debilitatingly cruel methods. It was not all love and happiness.

However, as we “move on toward perfection” (John Wesley), we must present a vision and a hope that opens the door to repentance and opportunity for the restoration of more and more of these treasured members of our families and of our world communities, our children. Let us not, as Christians, continue to turn a blind eye to the harm being done to them for the purpose of punishment over and against opportunities for restitution and forgiveness as tools for reconciliation. Let us truly see them and their God-given spark while doing all in our power to “love them to life.”

Notes

1 International Institute for Restorative Practices: Restoring community. Resourced from www.iirp.edu March 30, 2020.

2 J. Muncie, “The globalization of crime control – the Case of youth and juvenile justice: Neo-liberalism, policy, convergence, and international conventions” Journal of Theoretical Criminology. Vol. 9(1), 2005: 35-64; 1362-4806. See also C. Hackett and D. McClendon, “Christians remain world’s largest religious group, but they are declining in Europe”, Pew Research Center: Fact Tank, News in Numbers, April 5, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/. March 30, 2020.

3 N. Petrowski et al., “Estimating the number of children in formal alternative care: Challenges and results. Child Abuse and Neglect,” The International Journal, (70), 2017: 388-398.

4 Prison Fellowship International: Center for Justice and Reconciliation, “2007 Restorative justice Bible study: Where love and justice meet.” Retrieved from http://restorativejustice.org/am-site/media/love-and-justice.pdf. March 29, 2020.

5 Human Rights Watch, “Children behind bars: The global overuse of detention of children,” by Human rights watch. Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org. March 29, 2020.

6 Ibid.

7 ACLU “100 YEARS: Youth incarceration,” ACLU. Aclu. doi: https://www.aclu.org/issues/juvenile-justice/youth-incarceration (n.d.).

8 N. Petrowski et al., “Estimating the Number of Children in Formal Alternative Care: Challenges and Results”. Child Abuse and Neglect: The International Journal, (70), 2017: 388-398. Pub. Elsevier Ltd. New York, NY. Retrieved from www.elsevier.com/locate/chiabuneg

9 The Sentencing Project, “Racial disparities in youth commitments and arrests,” 2016. Retrieved from http://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/racial-disparities-in-youth-commitments-and-arrests/ March 29, 2020.

10 J. Flanagin, “Reservation to prison pipeline – Native Americans are the unseen victims of a broken U.S. justice system,” Quartz, April 27, 2015. Retrieved from https://qz.com/392342/native-americans-are-the-unseen-victims-of-a-broken-us-justice-system/. March 30, 2020.

11 W. Sawyer, “Youth confinement: the whole pie 2019,” Prison Policy Initiative, December 19,2019. Retrieved from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/youth2019.html. March 28, 2020.

12 S. Mulligan, “From retribution to repair: Juvenile justice and the history of restorative justice,” University of La Verne Law Review, 31(1), 2009:139-150.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.