Why should contexts of urban poverty so often be perceived as alien territory for the people of God, and hard places for the gospel? Through his experience in Kibera, a slum community in Nairobi, and through his reflection on the eschatological vision of Isaiah, the author discerns the Spirit of God at work in the burgeoning urban areas of poverty where many outsiders see little hope, and outlines a theological vision for the church’s missionary agenda there.

By Colin Smith

Introduction

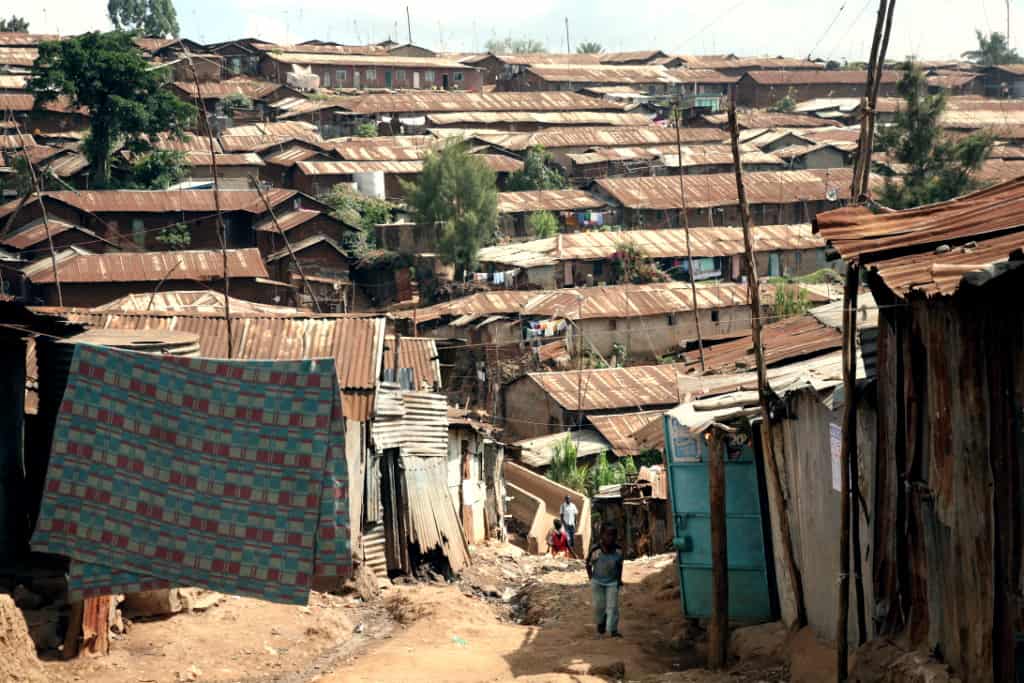

“How do you preach the gospel in a place like this?” The speaker had just entered the Centre for Urban Mission situated inside Kibera, Kenya’s largest and most infamous informal settlement or slum. Given that he had recently arrived from England to spend a week teaching theology students how to preach, his question was somewhat ironic yet refreshingly honest. It seemed as if a ten-minute walk through Kibera’s rubbish-strewn paths was enough to prompt a rapid re-evaluation of something which until then had been beyond question.

Those opening words posed an important question yet they also point to a more fundamental concern. Why should contexts of urban poverty so often be perceived as alien territory for the people of God, and hard places for the gospel? Do such communities challenge the viability of the gospel or might they equally be privileged places in which to discern more deeply its profound reality? This contrast in perception is largely a feature of one’s status as insider or outsider. Generally, reality is defined from positions of power and privilege. The “reality” of marginalised communities is often defined by the privileged outsider.1 Yet the gospel invites us to see reality through the eyes of one who “made himself nothing” (Phil. 2:7). For many who live, work or minister amongst the world’s one billion slum dwellers, urban poor communities are places in which the gospel is not merely proclaimed but is also discovered and encountered. The good news becomes not the hard thing for the outsider to preach, but the truth the insider experiences in the lived-out faith of a community.

This article explores what it means to discern the reality of the gospel at the margins of the city. The source of this reflection comes from my experience of being on the staff of both the Centre for Urban Mission and a local church in Kibera. Here I find myself being largely an outsider but also an insider; someone who comes from outside and lives outside this community and yet in my involvement in it have sought to listen, and discern the work of the Spirit from within. The other primary source in this reflection are the writings of the great urban poet and prophet of the Old Testament, Isaiah. It is through his visionary eyes that I hope to explore the nature of urban mission as a process rooted in a discernment of the ongoing work of the Spirit.

Seeing Things for What They Are

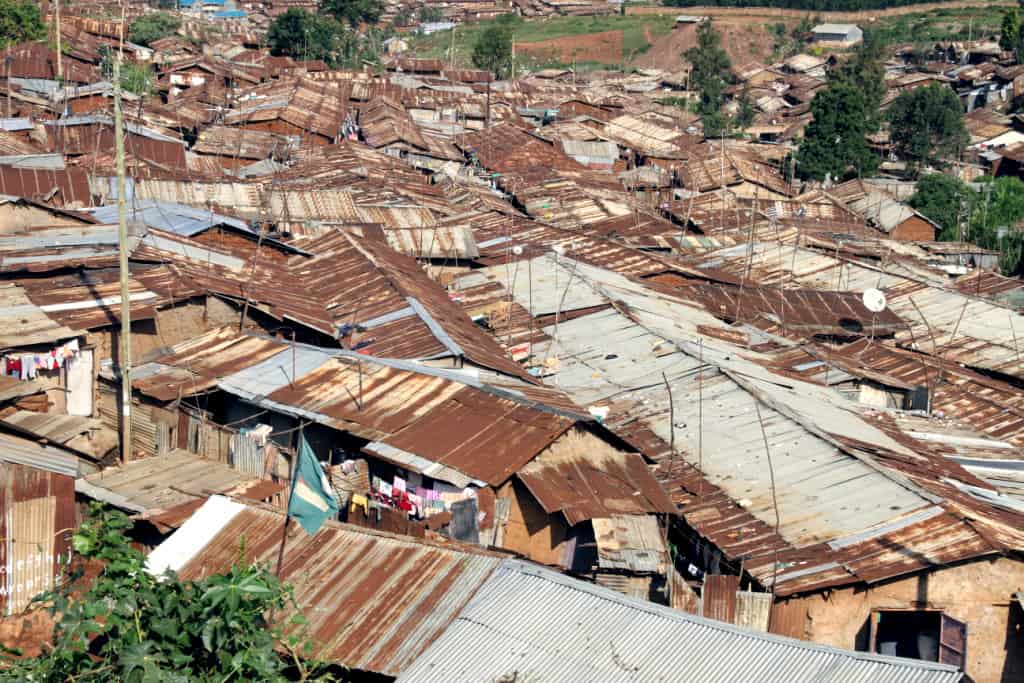

If we are to ask where urban mission begins I would suggest it must start with the recognition of the realities of the city. Prophetically it requires the naming of things for what they are. In cities, the very complexity of urban life makes this a difficult process. Cities are places of profound contradiction. In some sense they reveal both the best and worst of human civilisation. They are the highpoint of human achievement and the site of squalid human failure.2 They are places which bring vast numbers of people into close physical proximity, creating new forms and expressions of community, and yet they can equally be places of alienation and loneliness. Cities represent the creative gift of humanity to construct their own environment. They are centres of innovation in the fields of art, design and science, yet they can equally be places of profound ugliness and decay. Biblically this bipolar view of the city is frequently encapsulated in the language of Jerusalem and Babylon, an unresolved tension which continues into the final chapters of Revelation.

In the opening chapters of Isaiah we find the prophet confronting the city in its mass of contradictions. In the midst of national, moral, spiritual and economic decline, and in the face of rising Assyrian power, Isaiah names the city for what it is. Jerusalem is a city under siege (Isaiah 1:8), she has become the archetypal city of Rebellion, she is Sodom and Gomorrah (Isaiah 1:10). Drawing on Chapter 2, verses 6–9, Brueggemann3 notes the way Isaiah contrasts material fullness, “there is no end to their treasures” “full of silver and gold”, “filled with horses and no end of chariots” (Isaiah 2:7), with a disregard for the people of the city. He suggests the thesis Isaiah is presenting is of a city organised to abandon her people, a place where people no longer count, where the city becomes an empty form, filled with those treated as non-persons long since forsaken. His ancient but prophetic words echo the realities of many living at the social and economic periphery of the modern global city.

Cities are defined both by their built environment and by the communities which live and interact with that environment, both shaping it and being shaped by it. In this sense cities are never completely physical locations, rather they are places of social relations constructed by human activity and human culture.4 Ultimately it is the civitas, the community and culture of a city which makes it what it is and reveals what it is not.5 Like the Jerusalem of Isaiah’s day, cities can be full. Modern cities are centres of wealth, centres of power, home to iconic architecture, impressive skylines and flowing (or not so flowing) freeways. Yet they may also be empty–empty, that is, of the quality of relationship and human community which truly make a city “full”; “dead cities,” embodying an environmentally and socially bankrupt system of human settlement.6

Isaiah’s unashamed capacity to name what he sees is vividly revealed in Chapter 11:1 where the Royal line of David is dismissed as a mere stump. That which once had life, strength and power is now shown to be the haunt of termites, a dead thing whose glory belongs in the past and has no place in the present or future. It is a reminder of former greatness but not a source of future hope. The covenantal line of David, Israel’s divinely gifted kingship, is now a rotting stump, sawn off, without prospect for the future. Israel’s urban experiment is over; the city of promise is no longer.7

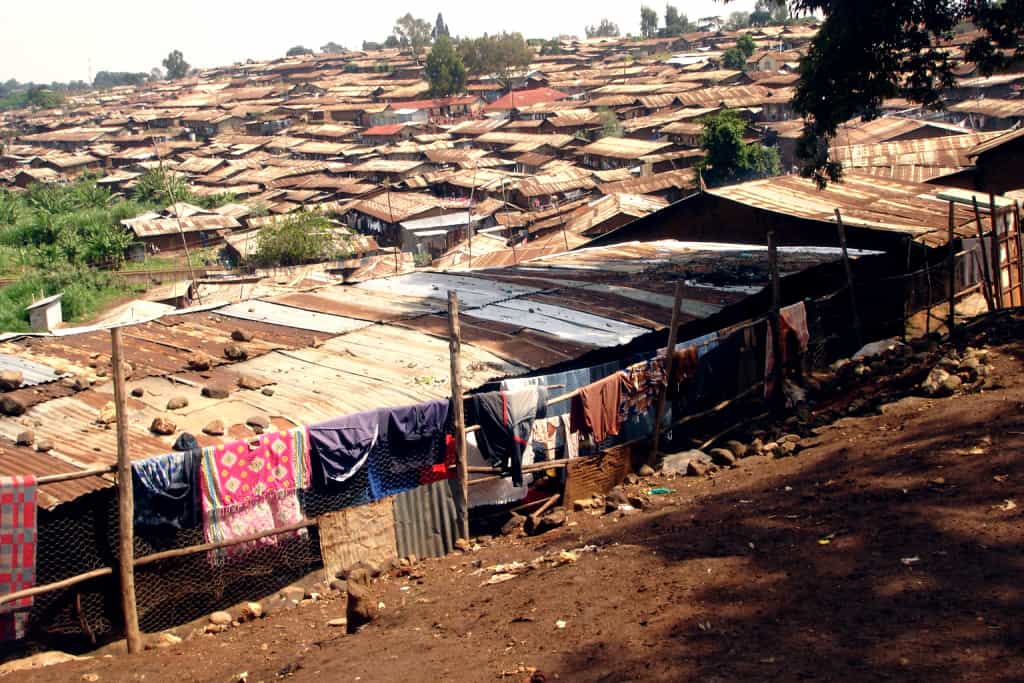

Urban mission requires this prophetic reality-check which Isaiah so pertinently and vividly reveals. Global capitals like Nairobi present us with that juxtaposition of fullness and emptiness. Almost 50% of Kenya’s wealth is held in Nairobi. Yet the poorest 10% of the city have just 1.6% of the city’s wealth.8 Nairobi’s wealth requires an ever-increasing ability to connect with the global economy yet while a minority suburban population obtains household connections to fibre-optic Internet technology almost half the city has no piped water in either their dwelling or their compound. Around the globe a billion slum dwellers live in similar conditions with impermanent housing, no security of tenure and little access to the material benefits of the city.

So far our discussions have focussed on the evidence of the Spirit in the life of the community with no reference to the presence of the local church. While the church is not the sole repository of the Spirit and the work of the Spirit is in no sense confined to the ministry of the church, we must expect that discerning the shoots of life in any community will inevitably take us to the life and witness of the local church. The church exists by mission just as fire exists by burning15 and the presence of the Spirit in the life of the urban church makes it a primary agent of community transformation. The emphasis here is placed very consciously on the agency of the Spirit not the facilitation of projects as the key to community transformation.

Like many others before us, at the Centre for Urban Mission we sought at first to work for the transformation of communities as if the church were merely another voluntary organisation whose social capital and volunteer spirit could be harnessed for carefully devised programmes. In our first year of working in Kibera we helped churches set up projects and programmes but discovered they did little to help people live out their discipleship in the community. We had separated discipleship from development and while some community change took place there was little sustainable and transforming impact on the church. Today we begin by seeking to discern the work of the Spirit in the life of local churches, listening to and hearing their own sense of God’s leading. We then work with them, building upon this sense of calling, through holistic discipleship training. In this process churches begin to discern what further ministries they will engage in or where and how they will extend their ongoing ministry in the community. As a result we have seen ministries growing and new ministries emerging; churches reaching out to their communities with HIV and AIDS ministries, economic empowerment programmes, homework clubs for the youth, and informal schools for children.

It requires a shift in mindset, a recognition of the work of the Spirit in the world, to enable churches to move into more transformational models of ministry and advocacy which require partnerships with local communities.

Whilst affirming the initiatives taken by churches to serve their locality we are confronted with the question of what it means for churches to become real catalysts for change, influencing the very structures of the communities in which they minister. Increasingly we are seeing that it is a church’s theology of the Spirit which implicitly or explicitly informs their understanding of engagement with a community. Where churches perceive the Spirit to be present only in the life of the church, then their involvement in community transformation is confined to service delivery by their members. In this instance churches are reluctant to involve community leaders and members of other faith communities on the basis that this is God’s work and therefore belongs within the church. It requires a shift in mindset, a recognition of the work of the Spirit in the world, to enable churches to move into more transformational models of ministry and advocacy which require partnerships with local communities.

Moving with the Spirit

John Taylor, in the opening sentence of The Go Between God, states that “the chief actor in the historic mission of the Christian Church has been the Holy Spirit”.16 His words are echoed by Newbigin who states, “It is not possible to stress too strongly that the beginning of mission is not an action of ours but the presence of a new reality, the presence of the Spirit of God in Power.”17 As Isaiah reflects on the shoot emerging from Israel’s erstwhile barren stump, he perceives that this new life finds its source and expression in the Spirit of God. The shoot is distinguished by the anointing of the Spirit upon it (Isaiah 11:2). Brueggemann notes:

It is the force of God, inexplicable and inscrutable, that turns stump to shoot, that imagines urban life out of decaying death. This breath of God blows where it wills. It has not been squeezed out or banished from the city. The city is still available for, addressed by, intruded upon by, this ruah.18

It is this Spirit of God in whom Isaiah can find hope for a future in which the poor and needy of the city will experience the justice and righteousness of God.

There are many winds blowing through our cities today. Winds of change, overturning traditional structures and reconfiguring family and community life; winds of global economics with the capacity to desiccate tender shoots of economic growth in the majority world; winds of global culture and mass media; winds of religious tension blowing amidst communities which have lived in peace for generations.

In the midst of this the breath of God, the ruah of God blows in the city (Isaiah 11:2–5). The Spirit blows–a Spirit of counsel or wisdom which comprehends the dynamics of urban life and provides prophetic leadership; a Spirit of power–not the oppressive power of the old dynasty, but power which protects the weak and vulnerable; a Spirit of knowledge and the fear of the Lord which leads to a discernment of what is true, just and right.

Here, in Isaiah’s pre-Pentecost, Pentecost the evidence of the Spirit’s outpouring on the city and her leader is manifest in wise judgement, discerning leadership, a levelling of inequality which will favour the needy and the poor of the earth. This profound link between Spirit and Justice lies at the heart of Isaiah’s vision of urban renewal and Godly leadership. Her future leadership will be belted and bound by Spirit-inspired righteousness and faithfulness (Isaiah 11:5).

Spiritual renewal and urban renewal become inseparable works of one and the same Spirit. Urban mission becomes a participation in that which God by his Spirit is doing in the life of the city.

Urban mission cannot be reduced to a set of well-executed projects, techniques and programmes, crafted through carefully written project proposals which satisfy demands of donor agencies. Neither can mission be confined to personal evangelism, the appeal of the crusade preacher, or the dynamic performance-based ministries of many mega-churches. For the prophet Isaiah, mission is the renewal of the city, her public life, literally her walls, streets and dwelling (Isaiah 58), her leadership, her governance, her rejection of greed and idolatry, her proclamation of the liberating news of Yahweh. Spiritual renewal and urban renewal become inseparable works of one and the same Spirit. Urban mission becomes a participation in that which God by his Spirit is doing in the life of the city. To discern the activity of the Spirit is to discern where, and through whom, the cause of the needy is heard and the poor receive justice. In this sense urban mission cannot be separated from an advocacy agenda nor from active participation with those who share a common cause with the rights and welfare of the urban poor.

Urban Mission and Eschatological Hope

The first five verses of Isaiah 11 point us towards the Spirit who renews the life of the city. However, from verse 6 there is an apparent change in register as Isaiah points towards a future where the whole of creation is reconciled to itself. Here, in this divinely ordained future the wolf will live with the lamb, the leopard lies down with the goat and in a dramatic reversal of Genesis chapter two, the threat of the serpent is somehow neutralised becoming of no danger to even the most vulnerable. This vision of restored creation may seem like a bridge too far. If this vision projects us beyond the horizons of our imagination what of the more immediate vision of a world where the poor find justice and judgements are made in favour of the needy? Are they too to be consigned to eschatological future beyond the reach of the immediate demands of the here and now?

Bevans and Shroeder remind us that eschatological hope remains as one of the constants of Christian mission, the anticipation of the full inauguration of the reign of God.19 The church finds its meaning, not within itself, but in the reign of God towards which it moves.20 Isaiah’s vision for the future goes beyond the restoration of the city and the nation, finding its fullest expression in the anticipation of God’s ultimate purpose. The central importance of eschatology in mission is that it defines the trajectories of hope. While the ultimate realisation of that hope lies beyond sight, vision and imagination, it nevertheless informs the direction of mission. The agrarian image of wolf and lamb finding harmonious existence may appear to have little apparent relevance to one billion slum dwellers who have more pressing daily concerns. Yet the significance of restored creation, an environment in harmony with itself is of central importance to those whose houses rest precariously on the side of polluted rivers, to those whose access to power and water continues to decline through environmental degradation. Similarly, the reconciliation of predator and victim has profound implications for communities torn by inner conflict or exploited by those holding wealth and power.

While the ultimate eschatological expectation may be manifest in the notion of the heavenly city (Isaiah 65:17ff) we are left to discern how that image informs our hope and mission in the city. For Isaiah that hope is well expressed in the term “faithful city” (Isaiah 1:21). It is a phrase that has specific content describing a city full of justice and righteousness, and empty of idolatry and false religion which ignores the plight of the widow and the fatherless. Ronald Peters, reflecting on the African-American experience, describes an “Egalitarian” city which he perceives as something akin to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “beloved community.” Drawing on a spiritual entitled “A City Called Heaven” he quotes the lines “I have heard of a city called heaven. I’ve started to make it my home.” He suggests this pointed not towards a sentimentalising of heaven, but rather towards the way the notion of the heavenly city provided an oppressed and enslaved community with vision and inspiration for the pursuit of a different society far removed from their current experience. This is not, he suggests, a form of utopianism but a faith-inspired quest for a society in which compassion and justice are not idealistic concepts but behavioural norms.21 It is this sense of the future reign of God which gives hope and content to our vision for the city and must give shape and direction to the mission of the church.

Conclusion

In the space of the first 6 verses in Isaiah 11 the prophet takes us from the death and demise of a discredited monarchy and a “dead city” to the restoration of the whole of creation. This whirlwind journey, from death to ultimate life, manages to articulate the realities of the present, and find inspiration for the future in the ongoing work of the Spirit, who invites us to participate in the eternal purposes of God. Bearing witness to the gospel at margins of the city, or any other community, draws us into this same process, the prophetic naming of realities, the discernment of the presence of the Spirit in the heart of the community, and the active participation in the work of the Spirit in pursuit of the city marked by justice and righteousness that is God’s delight.

Notes

1 See Robert Chambers, Whose Reality Counts?: Putting the Last First (London: ITDG Publishing, 1997).

2 T. J. Gorringe, A Theology of the Built Environment: Justice, Empowerment and Redemption (Cambridge: CUP, 2002), 145.

3 Walter Brueggemann, Using God’s Resources Wisely: Isaiah and Urban Possibility (Louisville: Westminster/John Knox Press, 1993), 7.

4 Elaine Graham and Stephen Lowe, What Makes a Good City? Public Theology and the Urban Church (London: Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd., 2009), 50.

5 Peter S. Hawkins, Civitas: Religious Interpretations of the City (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1986), xii.

6 Mike Davis, Dead Cities (New York: The New Press, 2002), 91.

7 Brueggemann, Using God’s Resources, 18.

8 Oxfam GB. Urban Poverty in Nairobi: Analysis and Appraisal (Oxford: Oxfam. Final report, May 2009), 26.

9 Graham and Lowe, What Makes a Good City?, 58.

10 Term used by the business press in the US to describe the ever-growing security industry. See Davis, Dead Cities, 12.

11 Bergmann in Graham and Lowe, What Makes a Good City?, 61.

12 See Abdou Maliq Simone, “Remaking Urban Life in Africa,” in Globalization and Urbanization in Africa, edited by Toyin Falola and Stephen J. Salm (Asmara: Africa World Press, Inc.), 67-92, for a description of the role played by informal economies in ordering and making provision for life in informal settlements.

13 Chambers, Whose Reality Counts?, 76.

14 Jean-Marc Ela, My Faith as an African (Nairobi: Acton Publishers, 2001), 8.

15 Brunner in Stephen B. Bevans and Roger P. Schroeder, Constants in Context: A Theology of Mission for Today (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2004), 8.

16 John V. Taylor, The Go-Between God: The Holy Spirit and Christian Mission (London: SCM, 1972), 3.

17 Lesslie L. Newbigin, “The Logic of Mission,” in Vol. 2 of New Directions in Mission and Evangelisation, edited by James A. Scherer and Stephen B. Bevans (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1992), 16-25. Originally published in Lesslie L. Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (London: SPCK, 1989), 19.

18 Brueggemann, Using God’s Resources, 18.

19 Bevans and Schroeder, Constants in Context, 34.

20 Ibid., 319.

21 Ronald E. Peters, Urban Ministry: An Introduction (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2007), 170.