Urban exegesis, a theological reading of the city, can be an insightful and effective lens for observing and interpreting any urban community. After considering some foundational elements of the Rainier Valley’s physical context, an examination of significant urban “cultural texts” in the community will explore cultural and theological meaning in the built environment of the neighborhood. This approach to observing and interpreting an urban community is essential not only for prospective church planters, but also for anyone who is seeking to embody an incarnational presence in the city.

By David Leong

As someone who is invested in my local urban community, people with an interest in Southeast Seattle occasionally ask me questions about the Rainier Valley. “Do you feel safe? How are the public schools? Are there gangs?” Over the past couple of years in particular, I’ve met with several young urban church planters across the denominational spectrum, all with a desire to start diverse, creative, “missional”1 faith communities in my neighborhood. Despite being one of the more churched2 areas in the city of Seattle, there appears to be something about the “up and coming”3 character of the Rainier Valley that has attracted these efforts. And as much as I’m genuinely encouraged by the good intentions of those with an interest in the Valley, there are also many issues to be considered carefully as people begin the process of what John Perkins has famously called the “3Rs”: relocation, reconciliation, and redistribution.4

As an interdisciplinary approach to observing and interpreting urban communities, urban exegesis, or “reading the city as a text,” seeks to understand the signs and symbols of the built environment as distinctly urban and theological contexts. In other words, urban exegesis provides a cultural and theological lens for interpreting the city.

My consistent advice has been to settle in to the community slowly, and to learn to read the community in its multi-layered cultural context,5 or to engage in what some urban missiologists have called “urban exegesis.”6 As an interdisciplinary approach to observing and interpreting urban communities, urban exegesis, or “reading the city as a text,” seeks to understand the signs and symbols of the built environment as distinctly urban and theological contexts. In other words, urban exegesis provides a cultural and theological lens for interpreting the city.

What follows is a brief case study of how applying methods in urban exegesis can help to illuminate specific aspects of an urban community. After considering some foundational elements of the Rainier Valley’s physical context, an examination of significant urban “cultural texts”7 (or sign objects) in the community will explore cultural and theological meaning in the built environment of the neighborhood. This approach to observing and interpreting an urban community is essential not only for prospective church planters, but also for anyone who is seeking to embody an incarnational presence in the city.

Seattle’s Rainier Valley

In geographic terms, a valley is an elongated geological depression, or more generally, a directional low point between surrounding land of a higher elevation. Valleys often receive the runoff of adjacent hills or mountains, serving as a natural drainage system for whatever is trickling down from the heights. In many cities, this metaphor carries over in a similar fashion. Urban valleys can function as literal and figurative low points in urban communities; they are frequently bounded by elevated land in proximity to more valuable commodities.8 Territorial views, better access to waterfront properties, and residential privacy are all benefits of living higher up. Meanwhile, those in the valley typically deal with whatever is left over. The reality that sewage, storm water, and waste runoff all seek the lowest geographic points for drainage is more than a function of gravity and fluid dynamics; it is also an everyday condition of life for those occupying the space at the bottom. In this regard, a valley and a gutter bear many similarities. Seattle’s Rainier Valley is an urban valley in this tradition, but as the city has grown significantly (geographically and economically) over the past decade, the Valley’s proximity to the urban core and other desirable amenities has catalyzed a large scale transition in the area.

Today, as one the most ethnically and socioeconomically diverse communities in the U.S.,9 the Rainier Valley is an eclectic mix of resettled refugees, working class immigrants, young urban professionals, and many people in between. Of the Valley’s roughly fifty thousand residents, 80 percent are people of color, 40 percent are foreign born, 45 percent speak a second language,10 and more than half are renters.11 On any given day, artists and activists, hipsters and soccer moms, transients and retirees can be found socializing in the local farmer’s market or loitering on the street corner near a liquor store. Named for the geographic orientation that points toward Mt. Rainier, the Rainier Valley is a roughly one-by-six mile urban corridor that runs through Southeast Seattle to the shore of Lake Washington. Its many diverse neighborhoods reflect a colorful history of triumph and tragedy, but recent years have brought controversial changes and contrasts that have left many wondering if the community can preserve its unique diversity.

Down Rainier Avenue

Heading south on Rainier Avenue, the Valley’s primary arterial, the area just past the intersection of Martin Luther King, Jr. Way reveals a variety of urban conditions that represent a fairly typical commercial thoroughfare in southeast Seattle. On the right side of the street, a triangular commercial block is shared by Ace Cash Express, the Rainier Laundromat, and the Minute Mart. Their common parking lot often serves as a communal overflow area for the locals who gather at the National Pride Car Wash just behind the Minute Mart. Neon signs and vinyl banners read “checks cashed/payday loans” and “fried chicken and cold beer” as neighbors congregate between parked Cadillacs near the bus stop. The police frequently show up to make their presence known, but the flashing lights of a squad car or two seem to have little effect at deterring the gatherings.

Continuing south on Rainier, groups of small, colorful storefronts—many with bars on their windows—are clustered together close to the sidewalks of the five-lane road. Most of the one or two story buildings are older structures in varied states of renewal or disrepair, from newly painted ethnic restaurants and markets to boarded-up industrial sites. Store signs that are written or printed in Vietnamese, Cambodian, Spanish, or Somali indicate the various immigrant populations present in the community. Despite this traditional urban landscape, each block is framed by a majestic collection of century-old trees that line the avenue in a curious contrast of gray concrete and dense greenery, a reminder of the thick forests that once surrounded the Rainier Valley.12 But the most noticeable contrast appears at Alaska Street, an official boundary of the Columbia City neighborhood.

The Columbia City Neighborhood

Contained in a relatively short, four block stretch of Rainier Avenue, right in the heart of the Rainier Valley, the Columbia City Landmark District is on the National Register of Historic Places at the center of this “neighborhood of nations”.13 Today, quaint storefronts and turn-of-the-century architecture frame each urban block in a seemingly innocuous restoration of this once dilapidated business district. Yet behind the trendy boutiques and restaurants is a very particular history, one that connotes community pride and successful revitalization for some, but class tensions and deep resentment for others. Whenever a neighborhood changes, there are always people on both sides of the change. Developers, investors, business owners, families, and residents interact in a complex, dynamic process that can shift the socioeconomic trajectory of a community, and sometimes evidence of these changes is inscribed in the physical geography of the built environment.

Angie’s Cocktails, a fixture of the “original” Columbia City, is a symbolic tavern of the old neighborhood. Described by some as a classic “dive bar,” Angie’s has been a favorite watering hole of local clientele for decades, particularly among the African-American community as a business with primarily black customers. With as many surveillance cameras as there are barstools,14 regulars come to shoot pool and enjoy cheap drinks, but for many newcomers in the neighborhood, a few too many incidents of seedy activity have soiled Angie’s reputation in recent years.15 Polarizing perspectives on the controversial bar have fragmented the community.

In 2000, directly across the street from Angie’s, the opening of the Columbia City Ale House signaled the changing demographics of the community. Offering “fine ales and splendid food” according to their full service menu, the new Ale House catered to a growing population of hipsters and professionals with very different tastes than those of the regulars at Angie’s. Noticeably more upscale and attentive to aesthetics, the Ale House predictably attracts a customer base that is mostly white. And as one might naturally expect, the Angie’s and Ale House crowds do not mix.

To the casual observer, these two bars, one on the west side of Rainier Avenue and the other on the east, are divided by what would appear to be little more than forty feet of asphalt and sidewalks. But locals know all too well that the cultural, socioeconomic, and historical distance is much greater. In this particular context, Rainier Avenue signifies an invisible boundary that segregates the gentrifiers of the future from the working class of the past. Both groups are working through these tensions in the present, but they are doing so independent of one another and on either side of Rainier Avenue. And as simply one point of interest among many in the Rainier Valley, these kinds of boundaries and obstacles pose specific challenges to the process of contextualization in a community marked by the pervasive and entrenched realities of urbanism.16

All of these urban objects are signifiers, structured vehicles of meaning lining the street like the trees that have seen more than a century of change in the Valley. Each object connects to the urban system of Rainier Avenue like branches on a tree, and together they shape the urban ecology of the community. As with any ecosystem, the urban cultural texts along Rainier are in a constant state of change as the life cycles of the city bring life, death, and rebirth in each season.

Reading the Signs in the Valley

Because of its unique identity as an area of distinct urban density, diversity, and disparity,17 the Valley is an ideal context for urban exegesis. In order to understand the physical, social, and economic attributes of the Valley, the observation component of urban exegesis calls for an urban socio-semiotic analysis18 of the Valley’s symbolic systems that signify density, diversity, and disparity in its various forms.

The process of observational analysis begins by locating urban sign objects within each domain, and then identifying their denotative and connotative meaning. Next, the form (signifier/object) and substance (signified/concept) of the signs are examined in cultural and historical context for any further symbolic meaning. Lastly, the sign is then “read” in its larger context of other signs in order to decipher any potential message or structure in the sign system. Its total meaning is constructed from these elements of semiotic analysis, which include both material (e.g., physical) and ideological (e.g., cultural) significance. To move toward an urban exegesis of the Rainier Valley community first requires an observational understanding of the multifaceted meaning of its built environment, social institutions, and economic indicators.

Signs of Urban Disparity: Columbia Plaza

Often connected to the urban attributes of density and diversity, urban disparity is exemplified in the close proximity of people and institutions of differing backgrounds and social strata. Disparate socioeconomic circumstances that normally stratify urban communities come together in communities that are undergoing some form of large scale transition. Exploring these points of adhesion between contrasting signs of disparity reveals urban sign objects that coexist in a state of tension. Nowhere in the Rainier Valley is this more apparent than in Columbia City, where transition and gentrification have created overlapping and interlocking pockets of both wealth and poverty.

The Columbia City Landmark District between South Alaska Street and South Hudson Street has 45 buildings constructed between 1891 and 1928 in a “cohesive urban mixed-use district which continues to convey Columbia City’s economic, social, and developmental history.”19 The small town feel of the turn-of-the-century storefronts and the restored brick pavers in the street match the period benches and light posts in the newly revitalized commercial areas. Along with the preservation and restoration that first popularized Columbia City as a trendy retail area has come a recent surge of economic development that has given the business district a strong local reputation for being completely gentrified. Though gentrification is an urban phenomenon that is difficult to measure quantitatively, the types of businesses in the Landmark District and the clientele they serve has changed dramatically over the past few years.

Locating Sign Objects’ Form and Substance

The clearest sign of urban disparity in the Columbia City neighborhood is the Columbia Plaza on Rainier Avenue, an old Tradewell Supermarket20 that was closed down during the community’s rough years of decline in the early 1970s. It later reopened as an informal mini-mall of local vendors specializing in a variety of eclectic merchandise, from car audio and electronics accessories to bulk cigarettes and athletic apparel. Both its exterior and interior structures communicate a variety of messages about the form and substance of urban disparity.

The exterior structure of the Columbia Plaza is a sign of the stark economic disparity present in the business district. Across the street from the Plaza, in contrast to the attractive glass storefronts of renovated retail boutiques and cafes, the plain, brown exterior of the old Tradewell grocery store is faded and peeling. No identifiable markings on the face of the large building exist aside from the large, white capital letters that read “Columbia Plaza” above the front door. All of the front windows have been boarded up and covered crudely, leaving the interior without any natural light. Lastly, the building is set back from the street because of the front parking lot, which further isolates the Plaza as an anomaly of blight in an otherwise “up and coming” neighborhood.

Inside the Plaza, a mix of casually divided stalls and kiosks sell discounted apparel, pre-paid cell phones, and other seemingly random items like used car alarms and subwoofers. The whole place has the feel of a swap meet or flea market as hand-written signs and unattended piles of merchandise clutter the space that has retained the vinyl floors and steel shelves of a 1970s grocery store. Though business was sustainable for many years before the gentrification began in the late 1990s, the early 2000s saw a steady decline in customer traffic. On weekdays, the Plaza often felt like a ghost town with only a few vendors supervising the variety of different “stores” inside.

While some local neighbors lament the decline of the Columbia Plaza because of what it once represented about the community, other residents are celebrating its demise as they look forward to its eventual replacement.

Thus the denotative form of the Plaza signifies an informal retail outlet where various “urban” goods and services can be purchased. Most consumers can identify these surface-level attributes of the Plaza’s signs without much critical thought for interpretation. However, the connotative substance of the Plaza is highly dependent on the socioeconomic context of the reader; and as a sign of urban disparity, its meaning shifts according to the social position and economic status of the person or institution interacting with the Plaza’s transition. While some local neighbors lament the decline of the Columbia Plaza because of what it once represented about the community, other residents are celebrating its demise as they look forward to its eventual replacement.

Community advocates for the Plaza admit that its retail presence could use a significant makeover in the community, but many proponents of its future development want to ensure that the current clientele they serve will continue to be served by a revitalized Plaza. They see the Plaza as an unpretentious, everyday kind of place, where shoppers of different socioeconomic backgrounds can have access to a variety of affordable goods. In their eyes, the Plaza is a sign of inclusion and affordability in an otherwise gentrified business district that is becoming increasingly expensive as it moves upscale.

On the other hand, the many critics of the Plaza cannot wait to demolish the structure because they view its continued presence in the community as a sign of the old neighborhood that struggled with crime and prostitution for decades before the redevelopment of the 1990s. Local neighbors have long complained about gang activity and drug dealing at the Plaza, and a fatal shooting over a dice game in the parking lot in March of 2007 further reinforced its reputation as a trouble spot in the transitioning commercial area.21 However, reported incidents of violence or criminal activity have been almost non-existent since then, though some continue to complain about the appearance of “suspicious” activities.22 A few young African-American men still occasionally park their SUVs, compare sound systems, and loiter in the Plaza’s parking lot during the day, but today their presence is largely fading in numbers in Columbia City altogether. For those who consider the Plaza the last blighted property in the Landmark District, its redevelopment into an entirely new commercial site cannot come soon enough.

Cultural and Historical Context

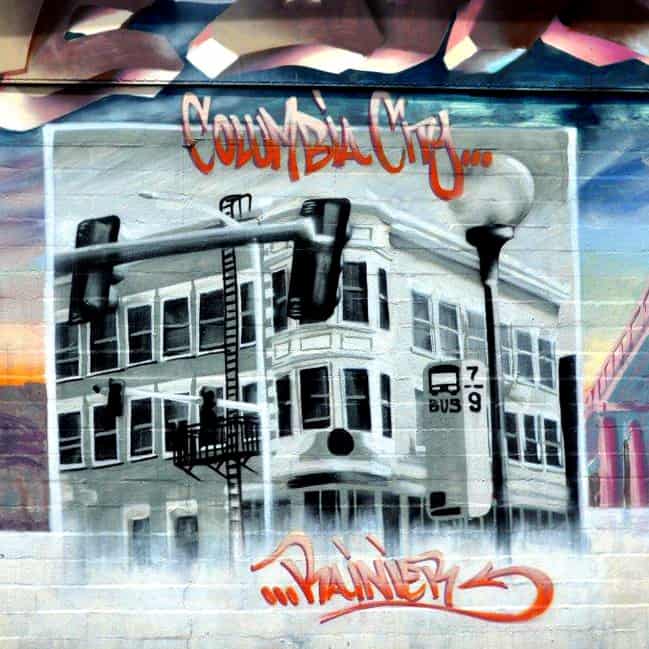

In the summer of 1994, a group of urban youth working with the People of Color Against AIDS Network (POCAAN) were commissioned by the City of Seattle’s Summer Youth Employment Program to paint a 75-foot mural on the south side of the Columbia Plaza building’s exterior wall. The public mural was designed by the youth as a tribute to their peers who had died from HIV/AIDS. With “vibrant colors and bold messages… the project allowed kids to pay homage to friends who had, as the mural puts it, ‘Gone 2 Young’”.23 However, not everyone in the neighborhood appreciated the art for its message of AIDS awareness and community solidarity.

In particular, Darla Morton, executive director of the Rainier Chamber of Commerce (RCC),24 felt that the style and feel of the mural looked too much like graffiti. “‘It looks like it’s been defaced,’ said Morton, who predicted the sanctioned spray-painting would inspire a rash of illegal ‘taggers’ in the business district.”25 But William Jones, a 15-year-old who helped to paint the mural, tried to explain that “for people who’ve left this earth, we’re bringing them back in our own way. We’ve brought their souls back.”26 Though many of the “youths likened their wall to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial”,27 Morton was not swayed.

In addition to the cultural gap between Rainier Chamber of Commerce and POCAAN, it is possible that the RCC’s reluctance to endorse the mural was connected to their desire to partner with the Neighborhood Farmers Market Alliance, a community-based organization that hosts neighborhood markets throughout the city of Seattle. In 1998, the Columbia City Farmers Market began meeting in the Columbia Plaza’s parking lot—right in front of the contested mural—during the spring and summer months. The Farmers Market brings fresh, organic produce and other local vendors to the neighborhood, and though some efforts have been made to create an accessible and inclusive market, the price point of organic goods and specialty food items has largely appealed to the upwardly mobile professionals in the community. With steady growth in this sort of customer base over the past decade’s gentrification, it is unlikely that many would understand or appreciate the public mural’s history and value to those who simply wanted to honor the memories of their friends.

Ultimately, the final signifier of the impending socioeconomic change in the neighborhood was the 2007 purchase of the Columbia Plaza by HAL Real Estate Investments, a Seattle-based developer that specializes in mixed-use commercial and residential properties. With permitted plans for 330 underground parking spaces, over eight thousand square feet of street-level retail space, and six stories of over 300 units of new housing,28 the proposed building will dwarf the old Plaza in both physical and social stature. Though an eventual replacement of the Plaza was inevitable, the sale of the Plaza for $6.6 million29 was a symbolic closing chapter for one of the last “original” businesses of the old Columbia City. Today, the Plaza is boarded up and awaits demolition. And as always, the redevelopment and transition has been welcomed by some, but is bittersweet for many others.

Coded Messages and Meaning

When a signifier like the old Columbia Plaza does not fit within the prevailing economic system because of its “ghetto” connotations—expressed in either low-income retailers or what looks like graffiti to some—it is bound to be transformed into a signifier that matches the economic codes of the structure in place.

Reading these signs of urban disparity in the context of Columbia City leads to an understanding that the most powerful codes structuring the change in the neighborhood are rooted in the patterns and regulatory practices of corporate-driven business economic development. The economic system of signs operates according to the flow of capital, and free market forces largely determine the outcome. When a signifier like the old Columbia Plaza does not fit within the prevailing economic system because of its “ghetto” connotations—expressed in either low-income retailers or what looks like graffiti to some—it is bound to be transformed into a signifier that matches the economic codes of the structure in place.

The general pace and character of gentrification can be mitigated by a variety of factors, but no amount of community organization or political will can eliminate the economic tendency toward the poles of either gentrification or decline in communities where points of disparity are both visible and common. The very presence of urban disparity in a community—various signs of wealth and poverty in close coexistence—means that transition in one direction or the other is not far behind. Signs almost always naturally group with like signs in the urban context, and these ordered similarities create stratified structures in the city.

Whether it is affordable senior housing being built over former dumping sites, public housing projects that have been transformed into mixed-income neighborhoods, or low-income retailers that are being converted into condos, all of these urban phenomena are symbolic systems of meaning in the larger Rainier Valley community. These signs of density, diversity, and disparity in the urban context can seem disjointed and difficult to read at times, and a part of that difficulty rests in the dynamic nature of the systems that shape the urban context.

A neighborhood is a like a living text, and as it evolves over time, so do the signs and the codes that govern them. The system of “grammar” may change, shifting the denotative and connotative meaning of signifiers’ form and substance. Signs that once represented positive aspects in a community can become negative, or negative signs can become neutral. But despite the perpetually shifting nature of urban neighborhoods, urban socio-semiotic analysis is still a relevant and effective method of locating, grouping, ordering, and interpreting signs in their immediate context. Like any language, becoming conversant with a broader vocabulary of signs, symbols, and codes (or words, ideas, and grammar) provides the reader with a more competent level of literacy and a more capable interpretive lens whenever the text, pseudo-text, or sign object changes.

A Community of Redistribution

A cultural exegesis of Columbia Plaza examines and evaluates a theology of community that is both contextual to the urban disparity of the Rainier Valley and faithful to the biblical narrative which calls the people of God to be an imaginative community of redistribution in a society that inherently drifts toward a disproportionate allocation of resources.

Theologically, to understand the culture of Columbia Plaza as a sign of disparity in the neighborhood requires an exploration of the missional implications of socioeconomic redistribution in a context of gentrification. A cultural exegesis of Columbia Plaza examines and evaluates a theology of community that is both contextual to the urban disparity of the Rainier Valley and faithful to the biblical narrative which calls the people of God to be an imaginative community of redistribution in a society that inherently drifts toward a disproportionate allocation of resources.

Gentrification with Justice

The Plaza is just one among many signs of disparity and gentrification in the Rainier Valley. Its scheduled redevelopment is symbolic of the final domino to fall in what has been a long line of businesses that have steadily turned over in the Columbia City business district. For many poorer residents in the community, debating the strategies of contextual economic development in tension with unbridled gentrification is a moot point because it is difficult for them to imagine how the area could become any more gentrified. However, there are others who are working to preserve the few remaining locally owned businesses that have a long history in the Landmark District, holding on to hope that Columbia City can retain its diverse character and unique history. Still others—many with the economic resources to support new development—are aggressively pushing for widespread business “revitalization”30 in the area because of the recognition that the potential for commercial growth among untapped consumer bases is strong.

Though it is quite clear that the reality of recent gentrification has significantly impacted the community in numerous ways, many well-intentioned people on all sides of the debate continue to disagree over the costs and benefits of gentrification for the Rainier Valley as a whole. Unfortunately (but predictably), the inherent socioeconomic disparity that stratifies groups in the urban context also segregates their respective understandings of change and development in the community. Regardless of whether gentrification is perceived as a potential tool in developing “a market with a conscience”,31 or merely the “new urban colonialism”,32 what is needed in this broader conversation is a willingness to explore creative options that allow for the market realities of urban redevelopment while also taking into account the importance of retaining and investing in the existing social fabric of communities that are likely candidates for targeted gentrification.33

“Gentrification with justice” is one such idea. As a compromise between the unregulated development of real estate and the urban isolation that inevitably leads to blight and deterioration, gentrification with justice suggests that while gentrification cannot be stopped (nor should it), its most damaging effects can be mitigated by an intentional process of inclusion that seeks to care for the long term sustainability of the poor.

Gentrification needs a theology to guide it.

“Gentrification with justice” – that’s what is needed to restore health to our urban neighborhoods. Needed are gentry with vision who have compassionate hearts as well as real estate acumen. We need gentry whose understanding of community includes the less-advantaged, who will use their competencies and connections to ensure that their lower-income neighbors share a stake in their revitalizing neighborhood. The city needs land-owning residents who are also faith-motivated, who yield to the tenets of their faith in the inevitable tension between value of neighbor over value of property. That is why gentrification needs a theology to guide it.34

A theology of gentrification in the context of urban disparity must hold social, economic, and theological concerns together in order to pursue a potentially holistic understanding of gentrification as a complex urban phenomenon. Ultimately, if gentrification is going to be connected to these multiple dimensions of justice, then it must function in such a way as to ensure that socioeconomic capital can be distributed fairly, generously, and with a particular concern for the “orphan, widow, and foreigner,”35 or the fatherless, the single mother, and the immigrant in the urban context. In cities where stark disparities so often dominate the urban landscape, this kind of distributive justice will inevitably be a re-distribution of resources.

Thinking about gentrification in these terms requires a theology that grasps the social and economic dimensions of redistribution, but also sees the theological capacity of redistribution as a redemptive communal practice. If gentrification is seen as primarily an economic issue, then redistribution of economic capital will simply be perceived as a form of punitive taxation on the upwardly mobile. On the other hand, if gentrification is seen only as a social issue, then redistribution of social capital will not be able to address the structural economic systems that perpetuate urban disparity. However, if a theology of gentrification binds both social and economic concerns together with a commitment to the biblical concept of Jubilee justice, then forms and practices of socioeconomic redistribution have the potential to be redemptive activities for the benefit of the whole community.

An Urban Jubilee Community

The year of Jubilee as described in Leviticus 25 is framed within in the broader Levitical context of the communal holiness of Israel. To practice jubilee was not merely a social and economic restructuring of society; first and foremost, this was a spiritual and religious commitment that grew out of the covenant with YHWH. “The priestly traditions view this as a community-wide enactment of release and freedom. The pragmatics of such an institution are, at best, difficult and complex, and the evidence for its practice is scant”36 However, regardless of how Jubilee was either idealized or implemented, “theologically, it remains an important aspect of the priestly vision of the Israelite community as the holy people of Yahweh”.37

Leviticus 25:8-17: The Year of Jubilee (NRSV)

You shall count off seven weeks of years, seven times seven years, so that the period of seven weeks of years gives forty-nine years. Then you shall have the trumpet sounded loud; on the tenth day of the seventh month—on the day of atonement—you shall have the trumpet sounded throughout all your land. And you shall hallow the fiftieth year and you shall proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you: you shall return, every one of you, to your property and every one of you to your family. That fiftieth year shall be a jubilee for you: you shall not sow, or reap the aftergrowth, or harvest the unpruned vines. For it is a jubilee; it shall be holy to you: you shall eat only what the field itself produces.

In this year of jubilee you shall return, every one of you, to your property. When you make a sale to your neighbor or buy from your neighbor, you shall not cheat one another. When you buy from your neighbor, you shall pay only for the number of years since the jubilee; the seller shall charge you only for the remaining crop-years. If the years are more, you shall increase the price, and if the years are fewer, you shall diminish the price; for it is a certain number of harvests that are being sold to you. You shall not cheat one another, but you shall fear your God; for I am the Lord your God.

Celebrated as a Sabbath of Sabbaths, Jubilee begins on the Day of Atonement (v. 9), which is a communal marker for penitence and forgiveness of the sins of the people. In this way, the social and economic ordinances that define the practice of Jubilee are rooted in a spiritual conviction that the redistribution of land, labor, and resources is an act of obedience to the holiness code that reconciles the community to God. The repeated imperatives that apply to “every one of you” (v. 10, v. 13) indicate the wide scope of this communal vision, and the layers of connection between rest, return, and financial integrity link generosity and simplicity with holiness and redemption.

However, it is important to remember that even though the root metaphor is the atonement of a holy covenant community, the economic implications of redistribution remain salient and essential to the practice of Jubilee. “The jubilee was intended to prevent the accumulation of the wealth of the nation in the hands of a very few… the biblical law is opposed to the monopolistic tendencies of unbridled capitalism”38 In the cultural context of Israel’s society, “this text represents an attempt to modify a contemporary economic praxis that was leading to the progressive economic deterioration of significant portions of the population.”39 Thus, the recognition of the importance of Jubilee is intimately connected with the reality of economic disparities that needed to be reconciled through redistribution.

Jubilee also reminds the people of God that they are stewards—and not owners—of the land, labor, and resources that they have been entrusted. These assets of the material economy were gifts to be managed for their flourishing, not commodities to be exploited. Treating workers fairly, setting slaves free, lending without interest, welcoming foreigners, and freely redistributing wealth are each reflections of an alternative economy in which YHWH is the arbiter of justice and righteousness. In the Jubilee economy, the culmination of Sabbath rest is the institution of this rhythm of communal justice in the life of the people Israel. Establishing Jubilee as a natural, recurring equalizer protected the poor and encouraged societal generosity as Israel sought to remember that all things truly do belong to God.

To contextualize Jubilee ethics in the present era of capitalism and consumerism is no simple task. But to live as a Jubilee community in the urban context is not just a solution to the free market forces that create disparity and gentrification; more importantly, it is a prophetic act of worship and submission to an alternative vision for society.

To contextualize Jubilee ethics in the present era of capitalism and consumerism is no simple task. But to live as a Jubilee community in the urban context is not just a solution to the free market forces that create disparity and gentrification; more importantly, it is a prophetic act of worship and submission to an alternative vision for society. Jesus was captured by this same vision in his proclamation of the good news in Luke’s gospel.

Luke 4:14-21: The Beginning of the Galilean Ministry (NRSV)

Then Jesus, filled with the power of the Spirit, returned to Galilee, and a report about him spread through all the surrounding country. He began to teach in their synagogues and was praised by everyone. When he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, he went to the synagogue on the sabbath day, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was given to him. He unrolled the scroll and found the place where it was written:

‘The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me

to bring good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to let the oppressed go free,

to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.’

And he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant, and sat down. The eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. Then he began to say to them, ‘Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.’

The prophetic imagination of Isaiah 61 is what enlivens Jesus’ proclamation of the fulfillment of the “year of the Lord’s favor.” As Jesus begins his public ministry with a declaration of Jubilee justice, he is announcing that the arrival of the Kingdom of God coincides with both the freedom and redistribution of Leviticus 25 and the hope and restoration of Isaiah 61. The reign that Jesus inaugurates casts an imaginative vision of beauty, strength, and redemption in the face of an oppressive empire that had all but crushed the longings of many who dreamt of a restored holy city on the Temple Mount. Directly after Jesus’ quotation of Isaiah 61:1-2 in Luke 4:18-19, the prophetic text continues:

to provide for those who mourn in Zion—

to give them a garland instead of ashes,

the oil of gladness instead of mourning,

the mantle of praise instead of a faint spirit.

They will be called oaks of righteousness,

the planting of the Lord, to display his glory.

They shall build up the ancient ruins,

they shall raise up the former devastations;

they shall repair the ruined cities,

the devastations of many generations. (Isa. 61:3-4)

In the same way that Isaiah sees a restoration of the urban devastation that has brought despair to so many generations, Jesus connects the good news of Jubilee with the rebuilding of the city. Just as “Isaiah links God’s new day for the poor with the promise of urban recovery,”40 Jesus’ gospel is one of renewal for those who are so often marginalized in the city. This renewed urban context is a place where the poor can share in the wealth of the rich, the captives can be released in the streets, the blind can see in a community of inclusion, and the oppressed are liberated by the justice of God. The faithful imagination of Isaiah that empowers Jesus’ ministry in Galilee must also capture the hearts and minds of Christ-followers in today’s cities.

Ultimately, a local theology of community in an urban context of disparity must shape the people of God into creative advocates of Jubilee justice and imaginative agents of redistribution. Redistribution in the diverse and stratified neighborhoods of the Rainier Valley may not look exactly like the Jubilee practices of Leviticus 25, but if a local theology of community can begin to challenge the inevitability of a gentrification that “tramples on the heads of the poor”41 through displacement and exclusion, then finding ways of creatively redistributing land, wealth, and access to equal opportunities should be the next step in the process. And while it is always important to be developing practical tools for implementation and engagement in the community,42 John Perkins also reminds those who are seeking to embody Jubilee ethics that “in the final analysis, there is no redistribution without relocation. The most important thing we have to redistribute is ourselves. Justice cannot be achieved by long distance… only after people are redistributed can we employ money in ways that produce development rather than dependency.”43 By linking redistribution with relocation, Perkins brings this missional theology of urban cultural engagement full circle in a return to the incarnational ethics of kenosis44 and downward mobility. These dialectical tasks are embodied, prophetic, and subversive expressions of a called and sent community in the city.

Conclusion

Despite the many challenges that the Valley has faced as the default drainage ditch of southeast Seattle, this portrayal of the Valley as a dumping ground is not the whole picture; thankfully, hard times have produced many positive elements in the community as well. Resilient and deeply rooted, long time residents of Rainier Valley take pride in the vast cultural, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity present in the neighborhoods. As a community with a strong identity and social conscience, many have worked hard to preserve the rich history of the area and cultivate a community of inclusion that values its multicultural heritage. Despite many ongoing historic problems, a high level of social capital has made the Valley an organized community, though this has not necessarily translated into tangible political capital.

Nevertheless, in the midst of widespread redevelopment and gentrification like what is happening in Columbia City, the Valley soldiers on in the struggle to retain its unique density, diversity, and disparity. Ultimately, learning to read the city as a text is a complex and contextual task that takes time and attention to the careful process of cultural and theological analysis. And though urban exegesis is always local, there is a locality in contextual theology that always informs the universality of cultural phenomena in other contexts.45 In this regard, urban exegesis can be an insightful and effective lens for observing and interpreting any urban community. There are many different ways to approach the complexities of the built environment in the urban context, but urban exegesis provides a distinctly interdisciplinary lens for practicing theological reading of the city.

Notes

1 What exactly is meant by the word “missional” varies, but for many it has come to mean a kind of ecclesial posture that is “sent.” Unfortunately, the meaning of “missional” has been significantly diluted in its widespread propagation among publications that equate the term with forms of church growth. Theologically, “missional” must be rooted in the missio Dei. See Darrell L. Guder and Lois Barrett, Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub., 1998).

2 The Rainier Valley has more churches per capita than many other residential regions in the city, many of which are small, “single-cell” ethnic congregations. Common denominations are the Church of God in Christ, Missionary Baptist, Assemblies of God, and various Pentecostal or non-denominational / evangelical churches.

3 “Up and coming” as it is used in reference to urban neighborhoods is essentially code language for gentrification. Communities that are transitioning toward upward mobility are labeled as “up and coming” as opposed to “formerly poor” for obvious reasons.

4 Perkins’ model of Christian Community Development has wide applicability (both contextually and theologically) beyond its usage in traditionally under-resourced communities. See John Perkins, With Justice for All (Ventura, CA: Regal Books, 2007).

5 The cultural context of any community always has physical, historical, social, economic, and theological dimensions.

6 Ray Bakke was the first to use the term casually in the 1970s at McCormick Theological Seminary. Technically, my definition of urban exegesis draws on the symbolic systems of urban semiotics and the missional theology of cultural exegesis in order to construct multi-faceted meaning in the urban environment. See David Leong, “Street Signs: Toward a Missional Theology of Urban Cultural Engagement” (Dissertation, School of Intercultural Studies, Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, CA, 2010).

7 In cultural semiotics, a “cultural text” is a basic unit of cultural analysis, or any cultural phenomena that signifies meaning. In the urban context, cultural texts can also be considered “urban sign objects.” See Robert J. Schreiter, Constructing Local Theologies (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1985).

8 “Urban” valleys are distinct from larger geographic valleys because they are typically low points within an already settled area, as opposed to a settled area bounded by underdeveloped land, in which case the valley may be thriving in comparison to its surroundings.

9 Though diversity is a difficult descriptor to quantify, numerous sources have identified the Rainier Valley as one of the most diverse communities in the U.S. See Jim Diers, Neighbor Power: Building Community the Seattle Way (Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2004), Sheryll Cashin, The Failures of Integration: How Race and Class Are Undermining the American Dream, 1st ed. (New York: Public Affairs, 2004), and G. Willow Wilson, “America’s Most Diverse Zip Code Shows the Way,” Associated Press, 2010.

10 The City of Seattle estimates that roughly 60 languages are spoken in the Rainier Valley community.

11 Leong, “Street Signs”.

12 The Rainier Avenue corridor is a historic thoroughfare that was first cleared by a rail line intended to connect the growing urban core with the unsettled area surrounding the Valley. “The Seattle Renton & Southern Railway built King County’s first true interurban railroad beginning in 1891, and spurred development of the then largely agricultural Rainier Valley” (Walt Crowley, “Seattle Renton & Southern Railway–King County’s First True Interurban,” History Link, 1999).

13 Diers, Neighbor Power.

14 Mike Lewis, “Angie’s Keeps Columbia City’s ‘Essence’ Alive as Area Changes,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, October 28, 2007.

15 Accusations of crack dealing, prostitution, underage drinking, and gang activity have plagued Angie’s for years. Recent changes in ownership have made attempts at cleaning up the bar’s tarnished image, but the reputation remains. Currently, there is ongoing litigation with community based support to revoke Angie’s liquor license (Casey McNerthney, “City Targets South Seattle Bar for State Action,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 29, 2009).

16 “Urbanism” studies the dynamic, holistic way of life in cities, as opposed to urbanization’s more static understanding of the city as a built environment. See Charles Edward Van Engen and Jude Tiersma, God So Loves the City: Seeking a Theology for Urban Mission (Monrovia, CA: MARC, 1994).

17 Density, diversity, and disparity are three attributes that define the urban context. See Leong, “Street Signs.”

18 For a primer on urban semiotics, see Mark Gottdiener and Alexandros Ph Lagopoulos, The City and the Sign: An Introduction to Urban Semiotics (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986).

19 This description is an excerpt from the National Park Service documents which placed the Columbia City business district on the National Register of historic places in 1980. Original documents were sourced from the Rainier Valley Historical Society.

20 Tradewell Supermarkets operated locally in Seattle (in addition to stores in Oregon and California) from the 1950s-1970s. Though the Columbia City location opened in 1958, the exact date of the closing is not known. Major decline in Columbia City hit bottom in the mid 1970s. See David Wilma, “Columbia Branch, the Seattle Public Library,” History Link, 2002.

21 Robert L. Jamieson, “A Violent Death in the Afternoon,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 2007.

22 These claims are not entirely unsubstantiated. On several occasions, I have witnessed casual encounters behind the Plaza that resemble all the indicators of a quick exchange of controlled substances. Common knowledge in the neighborhood is that occasional drug transactions persist at several locations in or around the Plaza.

23 Steven Goldsmith, “Mural’s Beauty Is in Eyes of Beholders,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 1994.

24 The RCC is the primary business association in the Landmark District, and has been a major player in the revitalization of the Columbia City commercial area along Rainier Avenue.

25 Goldsmith, “Mural.”

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Aubrey Cohen, “Developer Buys Columbia City Plaza,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, June 19, 2007.

29 Ibid.

30 Community “revitalization,” frequently used as a friendlier or more palatable term than “gentrification,” is often viewed with suspicion as a code word for development with the intent to displace “unwanted” populations. See J. John London Bruce Palen, Gentrification, Displacement, and Neighborhood Revitalization, Suny Series in Urban Public Policy; Variation: Suny Series on Urban Public Policy (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1984).

31 Robert Lupton, “Gentrification with Justice,” By Faith (June 2006; Issue 9).

32 Rowland Atkinson and Gary Bridge, Gentrification in a Global Context: The New Urban Colonialism, Housing and Society Series (New York, NY: Routledge, 2005).

33 It has been my continual assertion that searching for signs and symbols of urban disparity provides some of the clearest signifiers for change in communities undergoing transition.

34 Lupton, “Gentrification.”

35 The Old Testament makes numerous references to this “holy triad” in regard to the definition of justice. Both Israel’s communal life and the consistent witness of the Prophets have a particular concern for these vulnerable groups in society as an act of obedience to YHWH. See Walter Brueggemann, “The Church in Joyous Obedience: Biblical Expositions,” Laing Lectures (Vancouver, BC: Regent College, 2008).

36 Frank H. Gorman, Divine Presence and Community: A Commentary on the Book of Leviticus, International Theological Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1997), 138.

37 Ibid.

38 Gordon J. Wenham, The Book of Leviticus, The New International Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans, 1994), 323.

39 Erhard Gerstenberger, Leviticus: A Commentary. 1st American ed, The Old Testament Library (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), 398.

40 Mark R. Gornik, To Live in Peace: Biblical Faith and the Changing Inner City (Grand Rapids, MI: W.B. Eerdmans Pub., 2002), 28.

41 Amos 2:7

42 John Perkins and the CCDA provide a wealth of accessible resources for developing practices that cultivate socioeconomic redistribution in under-resourced communities. See John Perkins, Restoring At-Risk Communities: Doing It Together and Doing It Right (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1995), and Perkins, With Justice For All.

43 Perkins, With Justice For All, 192.

44 The self-emptying nature of Jesus in Philippians 2 is a central tenet of incarnational theology. See Ross Langmead, The Word Made Flesh: Towards an Incarnational Missiology (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2004).

45 The locality and universality of the city as a cultural context is a dialectical concept I explore in Leong, “Street Signs.”

4 thoughts on “Urban Exegesis in Seattle’s Rainier Valley”

Hey David,

I just wanted to thank you for writing and publishing this article. My “Leading in an ‘Unthinkable’ World” at ‘City of Peace’ reflects a similar perspective to your own about transforming urban communities by adopting Jubilee principles.

I’m in the process of formulating a civic proposal for a ‘holistic’ community and would like to assimilate the concept of Jubilee in its groundwork. There are legal frameworks that actually accommodate this type of ownership.

I wonder if you have any additional thoughts or ideas about utilizing these principles in the practical formation of an ‘Urban Jubilee Community’?

Brian

@Brian: Thanks for the comment, and the good question. As for the actual implementation of Jubilee practices, I’m currently reading through Richard Horsley’s “Covenant Economics” (WJK 2009), and have enjoyed it thus far. I think there are a lot of ways to approach Jubilee ethics in the city, many of which you are probably already aware, from land trusts and cohousing to community gardens and food bank cooperatives. For me, the challenge usually centers on, or is connected to, forms of sustainable and affordable housing. I’d love to hear if other have thought or written about ways to do urban Jubilee housing, or something along those lines.

Hi David,

Great article–I’m glad I got to sample a bit of the Big Dissertation! I do think that elaborating on the Jubilee concept is the way to go in approaching these economic issues. It’s going to be a Herculean task to convince the great swaths of conservative Evangelicals that ‘wealth redistribution’–an automatic dirty word in conservative circles–is actually a thoroughly biblical concept. But onward we forge.

At John’s Creative Liberation this evening we were thinking that Rainier Vista itself would be a good example of Gentrification with Justice.

But to be specific, I see that local government and community planning must be very conscious in maintaining services for a diverse community in the face of gentrification: low income housing, older and lower rent buildings for business serving ethnic and lower income communities, good transit that doesn’t get too expensive, a variety of social services, community centers for different ethnic groups, etc.

Rainier Valley is doing fairly well on most of these. One reason is the traditionally strong political support this area has gotten from the many elected leaders who have lived here, or who have at least paid attention to the strong voter turnout. Most recently, Mayor McGinn was put over the top by votes from Rainier Valley. The 37th District is also the strongest Democratic district in the state.

One thing that I think needs to be added to your analysis is the global context of society. I’m thinking specifically of climate change and peak oil, or more generally, environmental damage and resource depletion. We are at a major turning point in world history, but few realize it, especially among the poorer and ethnic communities here. Yet they will feel the effects, just like everyone else.

Fortunately we are better positioned here than in suburbia, with its extreme car dependence, but we have light rail only because of the foresight of some of those political leaders and of a handful of residents like myself. There is a need for an extended community-wide dialogue on where the world is headed and how we can adapt. For example, opponents of the light rail portrayed it as just another big, bad urban renewal project, not as a golden opportunity to prepare for a future of scarce and expensive fossil fuels, let alone as an opportunity for much better urban design. Even now John Fox’s Displacement Coalition opposes the kid of density (and yes, even some displacement around some transit stations) that is necessary for a successful transit-oriented future. In Columbia City I would replace the Columbia Plaza by a transit-oriented development but keep the buildings that house Justice Works and other non-upscale businesses.

This would also be a good opportunity to highlight how many other areas of the world are preparing for the future much better than we are. Discussing the decline of US empire and of US democracy will be critical if we want to avoid more debilitating wars and financial swindles. So we need a theology that goes far beyond gentrification, class, and race. Think systemic economic change, and the rise and fall of civilizations as documented in “Collapse” by Jared Diamond, or even the doomsday peak oil scenarios of John Michael Greer (“The Long Descent: A User’s Guide to the End of the Industrial Age”).