Title: Race and Place: How Urban Geography Shapes the Journey to Reconciliation

Author: David P. Leong

Publisher: Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2017

Pages: 200 plus end notes

Reviewer: Susan S. Baker

Most books about race focus on individual racism. Another segment of the literature includes an analysis of systemic racism, although usually done as a sociological treatise rather than to more effectively approach mission. Race and Place not only directly introduces systemic issues in a mission context but also includes the variable of place and how that affects and is affected by racial differentiation. This book should bring very thoughtful consideration to how we do mission as we utilize an action-reflection mode of approaching our mission role in God’s kingdom as it leads to reconciliation.

After a foreword written by Soong-Chan Rah, the book is divided into three main sections plus an introduction and conclusion. The introduction seeks to bring a more thorough understanding of the word race. The author notes, “We must understand how race is a complex, embodied reality that is always shaped by its cultural and geographic context” (p. 14). This, in turn, leads us into the first section, “Race and Place: Beginning the Journey,” in which the author assists us to better understand some of the terms he uses and then couches those terms within a confluence of theological and geographical research. Beginning with a delineation of cultural geographies and built environments, the author contrasts personal stories of Detroit and Seattle with the biblical stories of early Christian communities. As we review the biblical stories, we recognize how homogeneous the people of Israel were and how they understood that they were the favored people, the ones whom God chose as His own. But at times they lost sight of the fact that there was a purpose attached to their calling, that they were called in order to reach the nations for God. In the New Testament, Jewish Christians were challenged to recognize Samaritans and Gentiles as part of the community of God. Although these “others” were looked down upon, the New Testament relates how the church changed by obeying God and including these others. The author notes, “This ‘estrangement-turned-reconciliation’ is the heart of God whose very nature is radical belonging in community” (p. 34). The author applies this to our contemporary situation and exhorts us to turn from homogeneous “places” to embrace multi-ethnic places where we can live and participate in community with others who are different from us. He continues his explanation as “patterns of racial homogeneity and cultural sameness . . . perpetuate injustices of hierarchy and separation” (p. 37) which is the total opposite of the reconciliation we should be embracing.

Leong exhorts us to turn from homogeneous places to embrace multi-ethnic places where we can live and participate in community with others who are different from us.

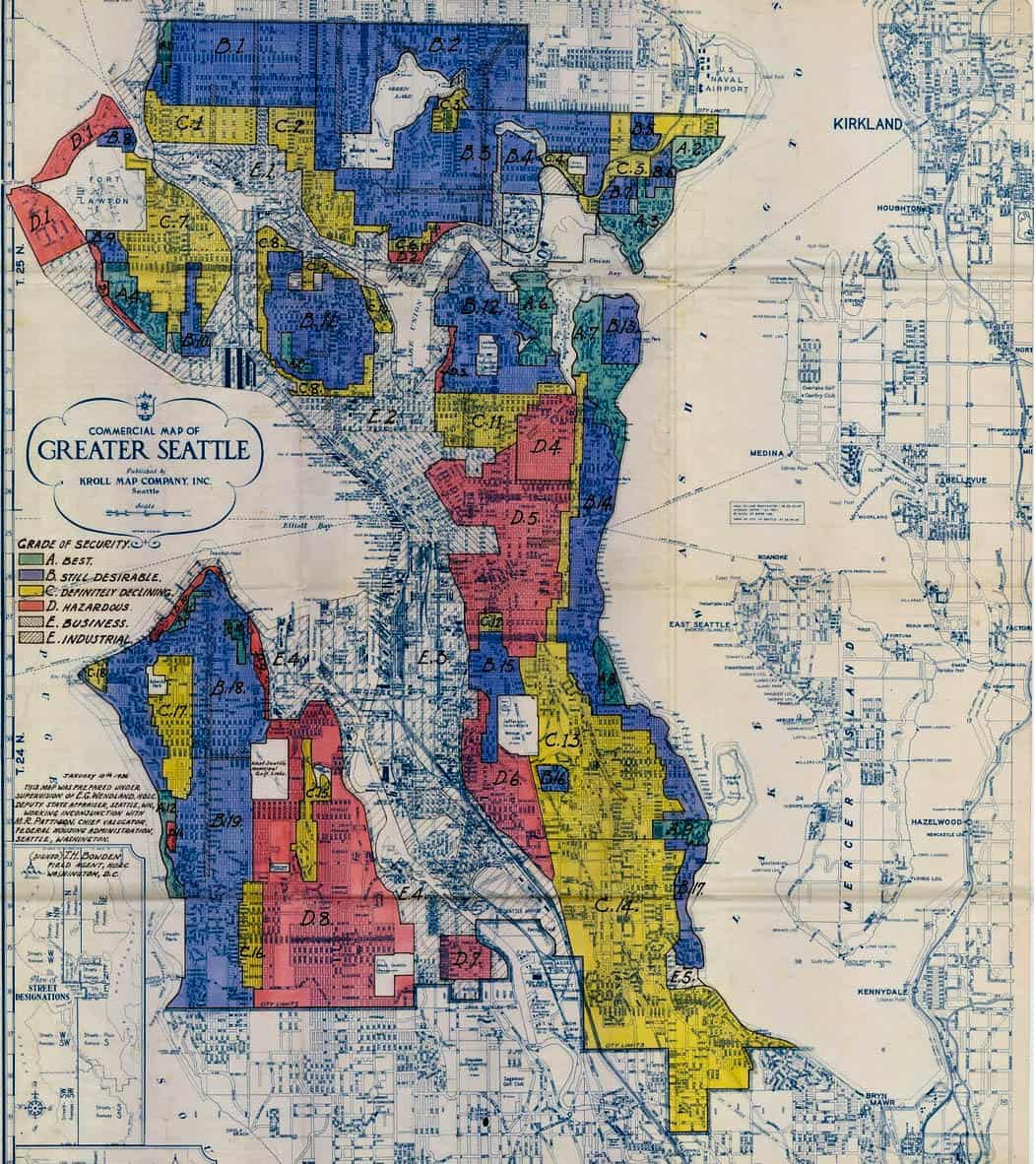

After providing needed theological underpinnings, the author continues in this section to define what racism is and how it is exhibited. Colorblindness is one term we often hear people use to define their relationships with those from other races. This term ignores the influence of history on the lives of individuals as well as communities. Looking at racial divides primarily as individual issues ignores the effects of societal manipulation which affect places. For example, what was the basis for deciding where to construct the new interstate highway system within a particular city? What “neutral” policies were instituted to determine how finances were divided among schools in the various neighborhoods of cities?

Why is it that Christians can answer a call to go overseas as a missionary but show real pause when it comes to going to the racially other in our own U.S. cities?

Finally, this section breaks down our misunderstanding of where we live our lives. “When it comes to locating our lives—residentially, vocationally, and socially—most of us have simply assumed that the natural course of things leads us to where we belong. But the reality is that particular priorities and choices are actually at work in this process” (p. 63). The author expounds on the idea of Christian calling, that as Christians we are called to love our neighbors and to have a special concern for the poor, the marginalized, the racially other of our communities. The author asks a question which I have often asked myself and that is, why is it that Christians can answer a call to go overseas as a missionary but show real pause when it comes to going to the racially other in our own U.S. cities? Along with this, if we are from the “favored” group, can we understand how we are privileged solely due to the color of our skin and, maybe more importantly, how we could actually be contributing to the very marginalization that others incur?

The second section of this book, “Patterns of Exclusion: Structures that Divide,” delves more deeply into how societal manipulations work to cause favoring some and excluding others. One statement I often hear is, “We have enacted the Civil Rights laws so there is no more racism in this country.” This was echoed in South Africa when I visited ministries there after the end of Apartheid was legislated. “Apartheid ended ten years ago. Why are the blacks still so angry?”

Leong answers this, “Laws often change much more quickly than our personal prejudices and cultural biases” (p.96). In the U.S. the Civil War was fought 150 years ago, yet we still are seeing that there are historical as well as contemporary effects of the sin of racism in the hearts of people and the institutions they establish. We may not still have as strong a system as slavery and then separate lunch counters or sitting at the back of the bus, but we do have what Leong calls “functionally separate communities” in which we can live, go to school, work, worship, shop, etc. and, or at least primarily, see only people who are just like us. The author is beginning to take us to a place of reconciliation which he recognizes is a necessary, albeit difficult, journey.

After an examination of the walls of hostility, the author asks, “Will Christians follow these patterns of exclusion or disrupt them?” This is such an important question. Basically, he is saying that there is no such thing as being “neutral.” This involves a choice. Will we locate our homes, our jobs, our churches in segregated (or homogeneous) communities or will we choose to locate where we live in community with those who are on the underside of society, who are legislated against and described in derogatory terms, who do not have the same access to those opportunities taken for granted by the “elite?” The author discusses this by reviewing the interrelatedness of place, parish, and ghetto, terms he explains quite thoroughly.

Will Christians follow structural patterns of exclusion or disrupt them?

Finally, this section discusses the issue of gentrification. Gentrification was defined by the author as “the process of redevelopment, transition, and the subsequent displacement of lower-income people that occurs in allegedly blighted neighborhoods” (p. 131). The author continues by describing how suburban living was considered the best place to live and raise families leading to “white flight” beginning in the 1950s and that now the tide seems to have turned with the white professional class wanting to be where the action is—buying and renovating architecturally attractive but decaying homes in areas close to the advantages of central city districts in what is being termed “return flight.”

Unfortunately, as the definition delineates, the lower-income current residents are displaced. The author sees the motivating factor leading to gentrification as a desire to be “cool.” Having seen gentrification firsthand in a number of U.S. cities, I do not resonate with the idea of “cool” or even necessarily that this is a current reaction against suburban living. Those desiring to return to the city are usually young professionals who work in the city and want to be close to certain amenities. However, when young couples begin having families, they often return to the suburbs.

Another point I should bring out is the complexity of gentrification. Most cities in the Midwest and Northeast have suffered economically over the last 50 years or so. Urban planners endorse gentrification as a possible means of regaining economic stability. The author does not spell this out but does recognize the need for profit raising strategies, noting that there is a difference between making a profit and maximizing a profit. This is a very complicated process, but as Christians we cannot ignore the idea of the marginalized being pushed around. The author asks, “Who is on the underside or outside of the transactions that resulted in this structural change in the community? Whose values or interests were cut short or cast aside in the excavation of the land?”

The third section, “Communities of Belonging: A Strange Family” directly takes the reader on a journey to racial reconciliation and the practical steps that can bring this about. The author begins this section by reflecting on the realm of academia and how too often what we learn is good theory which does not touch the ground to bring about real change. “It is not that the academic work is unimportant; it is rather that the conceptual learning must work in conjunction with the practical, relational, and experiential aspects of reconciliation as a lived theology, not just a textbook theory” (p. 158). He goes on to echo what Michael Polanyi calls “transformative apprenticeship” in order to move from the classroom to practical reconciliation. One step involved in this is to be committed to a place, to a community. It means listening to others and sharing your life with them, understanding and accepting differences yet being together as part of the community of God.

The concept of adoption is used in Scripture to describe how God accepts us as His children. God has beautifully and uniquely created each of us and has accepted us with our differences as His children. One of my children is adopted from a different country, a different culture, and a different color, but he is totally and completely my son. I love that we adopted him as it gave me a clearer understanding of how God adopted me and what it means. But adoption is done in community. In my case, adopting my son was done in family, in our church, and in a multicultural community in Chicago. Reconciliation happens in community and that is where we must live out our commitments.

The author resonates with the concept of action and reflection called praxis introduced by Paulo Freire. Leong states, “When thoughtful and committed Christians resolve to practice an informed and reflective faith, their embodied actions point to the kind of transforming and liberating power of the gospel as expressed by Jesus in Luke 4:18-19” (p. 177). He goes on to explore the “logic” of homogeneity which dictates the importance of comfort and safety which comes from being with people just like us, but then he reminds the readers about the other side—the underside—of that same logic. The author continues by wondering how we can “unlearn” this logic and focuses on the importance of “presence” in low-income, racially heterogeneous communities.

The “logic” of homogeneity dictates the importance of comfort and safety which comes from being with people just like us; and the danger of being with people unlike us.

This book is one of the best I have read to realign a Christian’s thinking to understand the importance of systemic racism and how we can combat the effects of racism through a new way of thinking of God’s calling on our lives. I believe this is important for all Christians who are cognizant of God’s call on their lives. It is a must-read book for all those considering participation in urban ministry.

1 thought on “Review: Race and Place: How Urban Geography Shapes the Journey to Reconciliation”

Thank you for an inviting book review that in itself advocates for gospel relevance–and cites the text I’m actually preaching this Sunday, from Luke 4.

I hope that the text addresses the complexities of multicultural teamwork and collaboration. Part of the conundrum that occurs is when people affirm the rightness of relocating into settings, where not everyone is so thrilled that they came. Transformative apprenticeship is a powerful concept, and those serving in such apprenticeships are often cued by the Holy Spirit to be a servant and learner, rather than a fixer. Often the path is not straight, because one has to work his or her way around the wreckage of past disappointments and broken trust. I do hope to read the book. Your review sparked that desire.