The young pastor took the Ted-X stage with confidence. His well-thought-out points and stories crafted and chosen in such a manner as to drive home his main point within seventeen minutes: bounded set thinking is bad, centered set thinking is good. This line of thinking has become popularized, so it seems, among many in the church today. Bounded set thinking has been labeled as legalistic or, worse, exclusive. Meanwhile, centered set thinking has been labeled as welcoming and inclusive. We seem to have demonized one to the detriment of the other. Set theory has been taught and approached through an “either/or” lens. Even in my own training it has been conveyed along these lines. But is this actually the case? Is it wrong to utilize the bounded set theory? Perhaps better yet, can we bring both bounded set and centered set thinking together so that they work in tandem for the overall health and well-being of a group? In this paper I hope to do just that. Instead of tearing down fences associated with set theory, I plan to show how we need to view set theory through a “both/and” lens and demonstrate that when we do so, we will understand how both the centered and bounded set work together and are not opposed to one another. Furthermore, we will apply this to life, specifically to how people experience change and growth.

The Popular Approach: Viewing Set Theory through the “Either/Or” Lens

As referred to in our opening story, it seems the popular approach to the bounded and centered sets is to view them as opposites or enemies, thus polarizing the two. Simply put, one is either “in” or it is “out.” One common way people try to explain bounded and centered sets is through the use of a farming metaphor. For instance, Alan and Debra Hirsch try to explain set theory referencing their Australian context:

In some farming communities, the farmers might build fences around their properties to keep their livestock in and the livestock of neighboring farms out. But in rural communities, where farms or ranches cover an enormous geographic area, fencing the property is out of the question. In our home of Australia, ranches (called stations) are so vast that fences are simply not a viable way of keeping the animals together. Under these conditions, a farmer has to sink a bore and create a well, a precious water supply in the outback. It is assumed that livestock, though they will stray, will never roam too far from the well, lest they die. As long as there is a supply of clean water, the livestock will remain close by.1

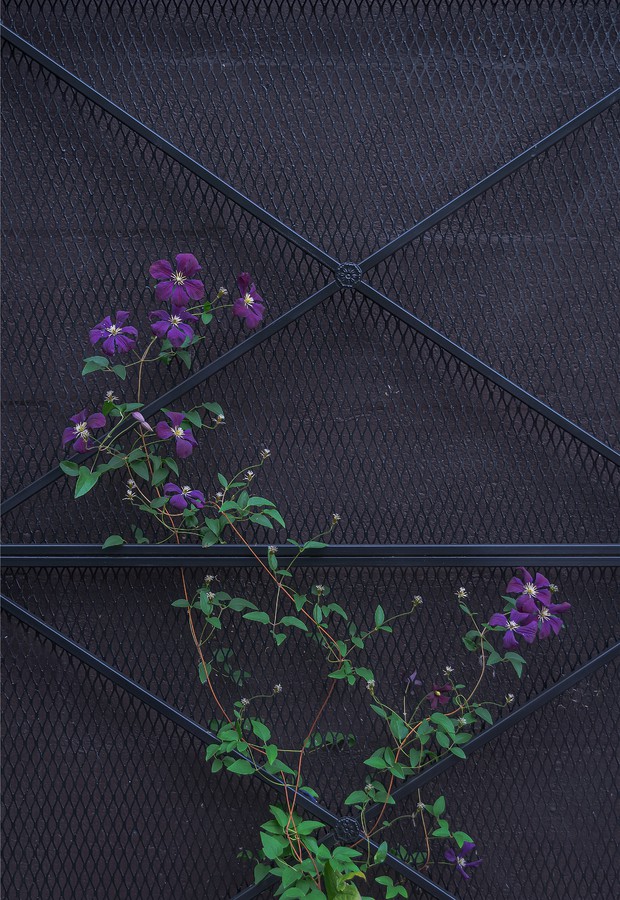

According to this example, the bounded set (fences) is confining and essential for demarcating who is “in” and who is “out” (see Fig. 1).

A few obvious examples of bounded set thinking can be seen in certain denominational distinctives. For instance, the Brethren in Christ baptize through triune immersion, kneeling and facing forward. This stands in contrast with dunking a baptismal candidate one time backwards. The Amish community is another example. This community is distinctly noticeable through their choice of plain clothes dress. These distinctives can be used in a manner that determines who is part of the community and who is not a committed part of the community. “Viewed in this light, most established institutions, including denominational systems, are clearly bounded sets.”2 According to this mode of thought, even such criterion as local church membership can be viewed as a bounded set and thus prohibitive, or at the least, less than ideal.

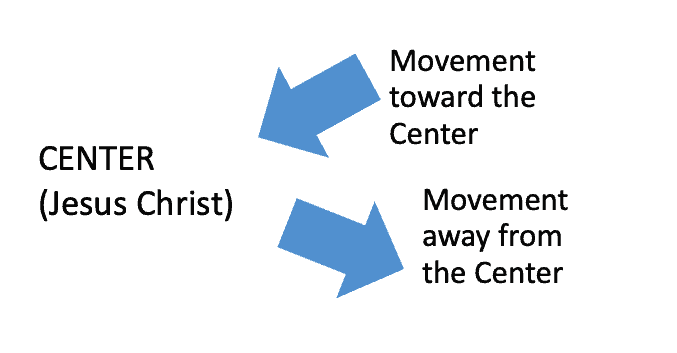

The centered set approach, on the other hand, has been displayed as the ideal approach. This approach emphasizes, and is not limited to, such markers as: (1) an open invitation, (2) degree of distance, either toward or away from the center, (3) belonging before believing, and (4) rather than “in” or “out” others are on the path (marked by core values and vision).3 This approach emphasizes the center rather than hard boundaries (see Fig. 2).

According to this figure there are no boundaries. People are free to either move toward the center or away from the center as they desire. What is important is the center (values, vision), not any hard boundaries. According to some, the centered set is the ideal because it is “unlike the more standard religious organizations with their theological and cultural boundaries and formulas developed to keep certain people in and others out.”4 Part of the main thrust of this discussion stems from an ecclesial understanding of the church and her mission. Perhaps an example of this can be seen in churches that welcome non-believers to participate as part of their worship team during Sunday morning worship gatherings. For instance, a gifted guitarist does not lead the team, but is welcomed as part of the team. Some hold that in this welcome there exists an evangelistic component that would not be possible if the church had hard boundaries in place. In other words, the non-believing guitarist, in being welcomed to the team, has a regular encounter with disciples and is potentially discipled toward Christ (the center) in the process. But does the bounded set thwart the missional movement of God through his Church? Some who hold to a strictly centered set approach would say yes. But is this indeed the case?

Bringing Bounded and Centered Set Together: Viewing the Discussion through the “Both/And” Lens of Christian Tradition

Perhaps a helpful way to examine this discussion involves a necessary change in our approach. The Christian faith has been a faith of “both/and” rather than “either/or.” Throughout the ages, whenever a person fell into an either/or view of Christian doctrine, the result veered into misunderstanding at best, and heresy at its worst. As a case in point, Roger Olson lays out for us the importance of a both/and approach in his book The Mosaic of Christian Belief: Twenty Centuries of Unity and Diversity. The both/and of Christianity is seen in the following doctrines:

- Christian Belief: Unity and Diversity

- Sources and Norms of Christian Belief: One and Many

- Divine Revelation: Universal and Particular

- Christian Scripture: Divine Word and Human Words

- God: Great and Good

- God: Three and One

- Creation: Good and Fallen

- Providence: Limited and Detailed

- Humanity: Essentially Good and Existentially Estranged

- Jesus Christ: God and Man

- Salvation: Objective and Subjective

- Salvation: Gift and Task

- The Church: Visible and Invisible

- Life Beyond Death: Continuity and Discontinuity

- The Kingdom of God: Already and Not Yet5

If the either/or is applied to any one of these doctrines, then the doctrine, and the Christian faith, cracks at its foundation. For instance, if I say that Jesus was only a man and not God, then I fall into the realm of false teaching known as Adoptionism. If I say that Jesus was only God and not man, then I fall into the realm of false teaching known as Gnosticism/Docetism. An orthodox Christian view of Jesus Christ is that he is both fully God and fully human.

Why do I bring this up in our discussion regarding set theory? I would like to see a call among the Church to view set theory through this same both/and lens that Christians have held since the beginning in regard to core doctrines of the faith. The either/or lens is both unnecessary and unhelpful.

John 1:14 – BOTH Grace AND Truth

A helpful case in point from the Scriptures can be found in John 1:14: “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. We have seen his glory, the glory of the one and only Son, who came from the Father, full of grace and truth” (NIV). Jesus came from the Father and he brought grace and truth. He did not bring merely grace or truth, not one to the neglect of the other, but both in the fullness of the Father’s glory.

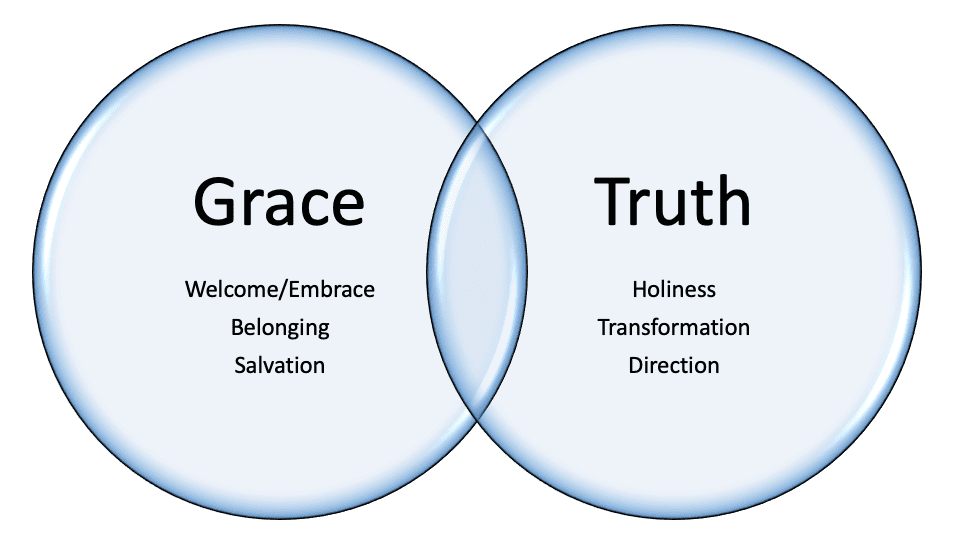

It is not uncommon today to encounter people in the Church who hold to either grace or truth. When the either/or lens is applied to grace and truth we see similar results as above in regard to set theory: Bounded Set = Truth; Centered Set = Grace. But this is not what Jesus revealed in its fullness. Jesus brought both grace and truth. These are not exclusive of one another, but rather they are interconnected. The way of Christ is always grace and truth, not merely one or the other. What is grace? What is truth? It is Jesus Christ! Regarding grace, “John likely has in mind the generous work of God in sending his Son, which results in our salvation.”6 As for truth, Jesus “describes himself as the truth (14:6).”7 Utilizing language of set theory, grace and truth might look as follows:

It is vitally important that Christ-followers learn to live in the tension of grace and truth. As we have seen briefly above, the Christian faith is one of both/and tension. Too often we desire to relieve the tension and fall to an either/or approach because we think that will make following Christ easier. In the end, that only serves to derail one’s faith journey. For instance, grace without truth can lead to a form of lived Gnosticism in which anything goes. What matters is spiritual, not the material. Likewise, truth without grace can lead one into a form of legalistic fundamentalism wherein the person can find themselves overly focused on the boundaries that grace is nowhere to be found. In essence, this person slips into a works-based form of pseudo-Christianity. How do we move forward from here? How do we take Jesus’ grace and truth and apply it to the area of set theory? Can we even do that?

Worldviews Matter

As anthropologist and missiologist Paul G. Hiebert reminds us, “At a fundamental level, worldviews are based on the way people form mental categories…. All cultures use both intrinsic and extrinsic categories.”8 In other words, both bounded and centered sets are part of a group’s worldview. Likewise, in light of John 1:14, both grace and truth must be part of a biblical worldview.

Alan and Deb Hirsch rightly point to Jesus as the center of the church, and thus the importance of the centered set approach. They state, for example:

Clearly Jesus’ faith community was a centered set, with himself at the center and all sorts of weird and wonderful people in his orbit–some far, some close, others edging closer, still others moving away. Clearly some disciples are closer to the center than others (Peter, James, and John), and at least one disciple drew away from the center (Judas). The Gospels speak of faith communities varying from twelve to one hundred and twenty, and make explicit reference to a number of women who traveled with Jesus. It seems that the community of Christ was not as simple as thirteen guys roaming the countryside. There was a rich intersection of relationships, with some nearer the center and others farther away, but all were openly invited to join in the kingdom-building enterprise. In many ways, this kind of movement allows for a sense of belonging before believing.9

While this sounds great, and it’s not untrue, there’s a sense that perhaps something is missing from this explanation. The Church is clearly called in Scripture to maintain a focus on Jesus Christ as Lord. But when we bring grace and truth together, the bounded and centered set, I believe we see a robust and challenging picture come to the forefront.

To illustrate this point, according to Mark 10:17-31, Jesus has an encounter with a rich man who desires to enter into the kingdom. The rich man claims to have kept the commandments related to maintaining a right relationship with other people. But then we witness Jesus say the following to the rich man:

Jesus looked at him and loved him. “One thing you lack,” he said. “Go, sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven. Then come, follow me.” At this the man’s face fell. He went away sad because he had great wealth. (Mark 10:21-22, NIV)

In this encounter we witness both grace and truth at work. First, Jesus is full of grace and shows this grace to the rich man. Jesus welcomes the rich man into his presence. He gives him time and attention, having a meaningful dialogue together with the man. We are even told that Jesus “looked at him and loved him.” Jesus is not looking to push the man away, nor make it especially difficult for this man to follow after him. Second, however, Jesus presents the truth to this rich man whom he loves. The truth in this instance pertains to idolatry–the rich man’s wealth has become his idol. Jesus’ words in verse 21 are a grace-filled call to embrace the truth: No one can have any idols before the Lord. This is truth, plain, simple, but hard. Interestingly, Jesus doesn’t chase the rich man down either. He welcomed him in grace, presented the truth in love, and allowed the man to make the decision, even if it meant he walked away. This is but one of many examples in which Jesus demonstrates for us how the both/and of grace and truth, the bounded and the centered set, must work in tandem.

The early church can teach us a few things on living in this tension. Alan Kreider lays out for us the effects of the early Christians holding to both the bounded and the centered set. Kreider writes:

Christian communities worked to transform the habitus of those who were candidates for membership–tinkering with their wiring, or even attempting a more far-reaching rewiring–by two means: catechesis, which rehabituated the candidates’ behavior by means of teaching and relationship (apprenticeship); and worship, the communities’ ultimate counterformative act, in which the new habitus was enacted and expressed with bodily eloquence.10

Notice Kreider’s language here: “transform the habitus”; “membership”; “tinkering with their wiring”; “rewiring”; “rehabituate”; “counterformative.” This seems to be heavy on the truth or bounded set side of the discussion. But there is also language of grace and centered set thinking present: “communities”; “relationship (apprenticeship).”

As a case in point, Kreider demonstrates how the early church had a strong culture related to the issue of life. Generally, the early church Fathers were in agreement that no Christian should participate in the gladiatorial games as entertainment, join the Roman legion, or engage in abortion or death by exposure for infants. Pertaining to the missional effect of this, Kreider states, “It is doubtful that the Christian’s repudiation of the most popular form of entertainment enhanced their missional prospects!… This must have limited Christianity’s attractiveness to some people.”11 Perhaps this is what the Church was experiencing following the death of Ananias and Sapphira according to Luke in Acts 5:13, “No one else dared join them, even though they were highly regarded by the people.” There was grace (centered set) in the Church’s welcome and mission, but truth (bounded set) was equally essential in the Church as an alternate community.

Set Theory and the Church’s Mission

For the Church to be the missional people of God at work in the world for his glory, both the bounded and centered set need to be held together in tension. When Christians hold to a centered set to the neglect of the bounded set in the name of mission, the Church becomes lop-sided, speaking the language of belonging but neglecting the transformational power of the gospel. “Missional communities are more than centered-set congregations. A pilgrim, covenant people require an alternative way of life. This calls for bounded-set identity.”12 Furthermore,

This journey as a pilgrim people, calls for commitment to practices of the reign of God that can be made only in covenant relationship. Such practices need to be encountered and demonstrated so that people might see the implications of the journey. The covenant community is a bounded set composed of those who have chosen to take on the commitment, practices, and disciplines that make them a distinct, missionary community.13

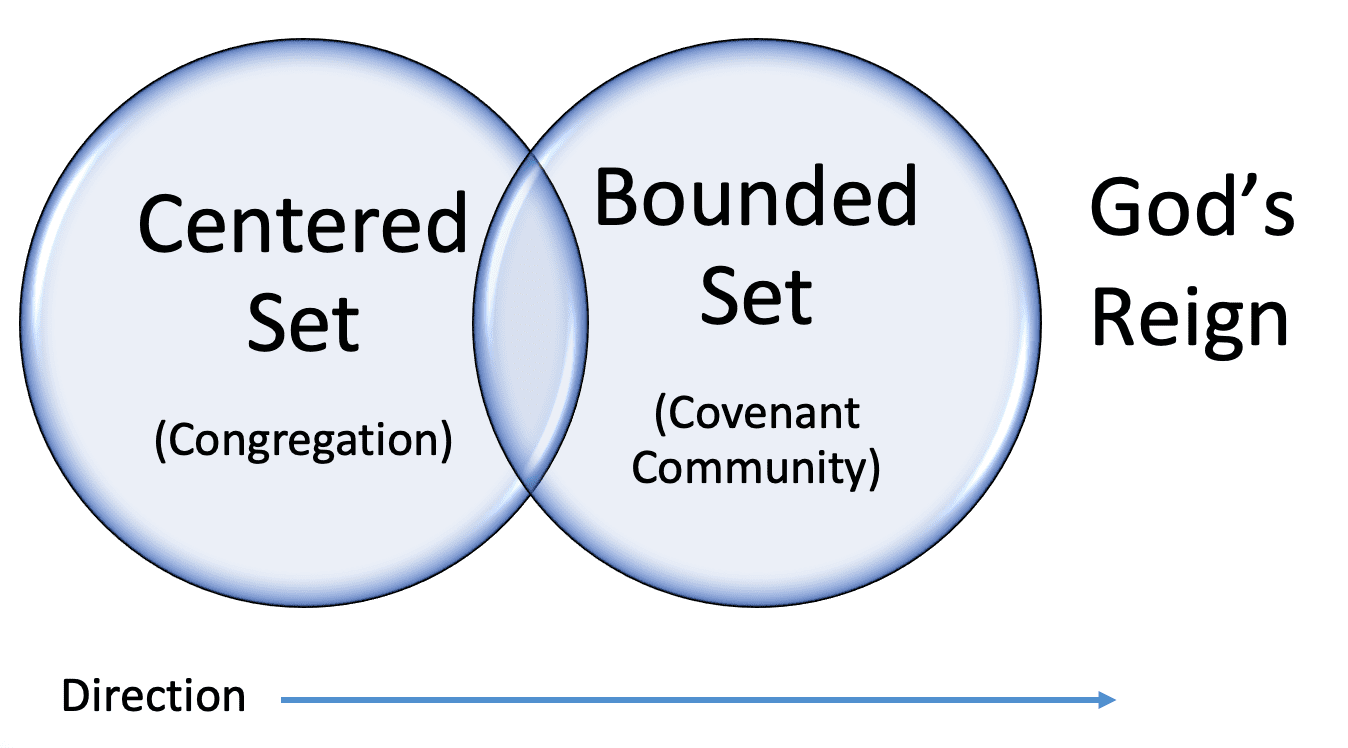

Figure 4, which is adapted from Darrell Guder,14 attempts to demonstrate this reality. The Church is not stagnant, but rather it is moving somewhere. The Church is moving toward the fullness of God’s reign, Christ’s kingdom reality. The centered set would be the larger congregation. This is the mix of people that Hirsch and Hirsch speak of as quoted above. The congregation is comprised of those who are seeking but not yet committed, those who are exploring, experiencing serious doubts, interested in Jesus but not sure. These are the ones, like the rich man in Mark 10, who are interested in eternal life but perhaps have not made a deeper commitment yet. On the other hand, the bounded set would be the covenant community rooted in Christ. They are the ones who have counted the cost of following Christ and are deeply committed to him. These comprise what Alan Hirsch and Dave Ferguson call communitas:

The word communitas captures the idea of the enhanced forms of community that emerges from the context of shared ordeal, a common task, an organizational challenge, even danger. The context of the challenge forces a restructuring of the basic relational fabric of the group. In such situations, people move from being associates to becoming comrades, from being acquaintances who happen to bump into each other at church-related activities to being partners bound together in a common cause.15

The language of moving from “acquaintances” and “associates” to “comrades” and “partners bound together” indicates that the church is always comprised of both the centered set and the bounded set. But the church clearly needs the bounded set at the center in order to move forward. Without the bounded set at the core, the community has no direction and potentially becomes stagnant. The “common cause” becomes the bounded set. In this case, the common cause is the reign of God and his kingdom in Christ. What does this look like on the ground? How does this look in ministry today?

Grace, Truth, And Time

How do people grow and mature in a healthy manner? Henry Cloud proposes three ingredients are necessary for this to happen: grace, truth, and time.16 Cloud writes, agreeing with what we touched on above in regard to John 1:14:

The very character of Jesus is one that includes exactly what we need to grow: grace and truth. And when he came to visit us and intervene in our lives, he dwelt with us. He spent time in the process with us and still does even now. Ever since the Garden of Eden when we fell away from, [sic] He has had a plan that included His grace, His truth, and a lot of time to work it out.17

Grace and truth are necessary for our growth and transformation. If I’m hungry and in a hurry, I could microwave a piece of leftover pizza for a quick dinner. But the microwave approach will leave the pizza hot but floppy. The best way to re-heat a slice of pizza involves pre-heating the oven, putting the pizza in the oven, then waiting until it is just the right amount of crispness and heat. However, that takes more time. The same is true for transformation and growth. As Cloud points out, time is also a vital component to the growth process. If we try to rush growth, then we get a “half-baked person.”18 Growth is a process, and that process calls for our deep commitment and involvement. We cannot grow without these elements. The centered set invites us into this process while the bounded set provides the ideal or the vision upon which we focus–Christlikeness, holiness, humility, justice, etc. (e.g., the Fruit of the Spirit, Gal. 5:22-23). Again, grace, truth, and time are all equally needed for this to take place. If one ingredient is missing, then we get the following:

- “Grace and time together, without truth, will make you comfortable in your stuckness.”

- “Truth and time together, without grace, will discourage and break you.”

- “Grace and truth together, without time, will give you a vision and then not have you reach the completion of that vision.”

One area in which I have seen this play out on a daily basis was in my work with the homeless population. There is a myriad of reasons for people to experience homelessness: trauma, addiction, abuse, mental health, etc. But in this work, grace, truth, and time are needed to serve and minister faithfully to this vulnerable population. If we show grace and time, but withhold truth, that can result in a homeless person getting stuck in their recovery. When this happens, they can grow comfortable in the shelter, not doing what is needed in order to move forward. If we show truth and time, but withhold grace, then the homeless shelter can take on the feel of a prison. This approach only leads to frustration and can push someone out of the shelter before they are ready. When this happens, the same cycles that led the person to the shelter persist and they usually come back to the shelter again at a future time. If we show grace and truth together, but withhold time, this can result in deflating a person rather than building them up in Christ. When grace and truth are held out as the vision, but time is not an ingredient, the process succumbs to idealism rather than focusing on the practical day-to-day wins as they come. In all of this, both the bounded set and centered set are equally at work. Indeed, both are necessary for any community to grow, progress, and experience the transforming power of Jesus Christ.

Conclusion

While on a popular level it has become fashionable to view bounded set and centered set thinking as opposed to each other, we have demonstrated, however, that for healthy growth to take place within community, as well as for individuals, both the bounded set and the centered set need to be working together. The centered set welcomes into community those who are seeking, questioning, etc., while the bounded set acts as the vision and direction in which the entire community is headed. Without both of these, the community breaks down and loses its purpose. Added to this is the element of time, which is necessary for the working out of this relationship between bounded set and centered set (i.e., grace and truth) thinking. The Church, since its inception, has been called to be an alternative community in comparison with the ways of the kingdoms of this world. The Church is to be a signpost, a foretaste of God’s reign and his kingdom here in earth. In order for this to be reality, the Church must hold to God’s kingdom ethics demonstrated clearly in the life and teaching of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. This acts as the bounded set for the community. But in this, the Church welcomes those on the margins, shows them grace and love, and the alternative way of the kingdom of heaven. Living into this causes tension, but Christ-followers are called to live in this tension. As Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon remind us, “Our ethic is distinctive in its content. Christian ethics is about following this Jew from Nazareth, being a part of his people. Therefore, this ethics will probably not make much sense unless one knows that story, sees that vision, is part of that people.”20 This is why it is imperative for the Church to be a both/and people. A people wholly committed to welcoming others in grace, but also wholly committed to embodying the ethics of Christ and his kingdom. An either/or approach will not get us to where Christ is calling us. It’s time for the Church to mend some fences in regard to set theory, with an eye toward our growth and maturity in Jesus Christ.

Notes

1 Alan and Debra Hirsch, Untamed: Reactivating a Missional Form of Discipleship (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2010), 152.

2 Ibid., 153.

3 Ibid., 153-54.

4 Ibid., 153.

5 Roger E. Olson, The Mosaic of Christian Belief: Twenty Centuries of Unity and Diversity (Downers Grove: IVP, 2002).

6 Gary M. Burge, John: The NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2000), 59.

7 Ibid., 60.

8 Paul G. Hiebert, Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2008), 33, 35.

9 Hirsch and Hirsch, Untamed, 154.

10 Alan Kreider, The Patient Ferment of the Early Church: The Improbable Rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2016), 41.

11 Kreider, Patient Ferment, 117, 18.

12 Darrell L. Guder, ed., Missional Church: A Vision for the Sending of the Church in North America (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 207.

13 Ibid., 207-08.

14 Figure 4 is adapted from Guder, ed., Missional Church, 208-10.

15 Alan Hirsch and David Ferguson, On the Verge: A Journey into the Apostolic Future of the Church (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 138.

16 Henry Cloud, “Ingredients of Growth,” Cloud-Townsend Resources, 6 July 2000, https://cloudtownsend.com/ingredients-of-growth

17 Cloud, “Ingredients of Growth.”

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Stanley Hauerwas and William H. Willimon, Resident Aliens: Life in the Christian Colony (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1989), 102.

2 thoughts on “Mending Fences: Viewing Set Theory Through a “Both/And” Lens”

Thank you for this timely teaching. I found it very interesting, engaging, meaningful and applicable.

Thank you for your comment. I’m grateful you found the article helpful.