Presentation Given at May 4, 2022 Colloquium

Part of Educating Urban Ministers in Philadelphia After 2020 project

Presentation Question: What new shape of ministry leadership and innovations in ministry are required in the post-pandemic world, and what is required of theological education institutions to address these needs?

Introduction

The amount and frequency of change our world has experienced in recent years is staggering and has sent many theological education institutions into a dizzying state of disorientation. What should be done to adapt – or rethink entirely – our approach to training present and future kingdom leaders in such a significant time of change? And what implications should this have on how seminaries are led, structured, and funded? This paper will seek to offer a direct, practical, and hope-filled response to these questions.

As theologian Walter Brueggeman wrote, the movement of the biblical story of God’s people was orientation to disorientation to reorientation.1 For the past few centuries the church in North America felt a sense of orientation, where (relatively speaking) much was right in how it understood and assumed a prominent place in society. However, over the past few decades the church in the West has felt the effects of post-Christendom, where the church is no longer at the center of society. Thus, the church has been pushed to the edges, no longer able to enjoy a privileged place at the cultural table it once knew.

Even before the pandemic, the church in the West was in a state of crisis. Over the past few decades, North American church leaders slowly realized what our brothers and sisters in Australia, the United Kingdom, and Europe have felt for some time, that the church no longer enjoyed the credibility, cachet, and influence it once held. Some have described the pandemic as a global x-ray, revealing the contours and realities of what our systems and assumptions truly are. And much has been revealed. How, then, will the church respond, and how will theological education institutions link arms with the church to faithfully pursue the Great Commission? Lest we become too discouraged in this space, South African missiologist David Bosch provides crucial perspective:

Strictly speaking one ought to say that the Church is always in a state of crisis and that its greatest shortcoming is that it is only occasionally aware of it… That there were so many centuries of crisis-free existence for the Church was therefore an abnormality… Let us also know that to encounter crisis is to encounter the possibility of truly being the Church.2

In Part 1 we will address the new shape of ministry leadership and the innovations in ministry required in a post-pandemic world. We will explore the fundamental shifts needed in order to make the gospel relatable and accessible to people in today’s culture, while remaining faithful to the gospel message. And in Part 2 we will explore specific implications and practical applications regarding the shifts that seminaries must experience.

Part 1: Necessary Shifts

It is important to begin with a teleological approach: “What is the end goal of a seminary?” As JR Rozko and Doug Paul point out in their white paper on the missiological future of theological education, it is important to acknowledge that seminaries have been shaped largely within a Christendom mindset and context.3 How then can we assume effective ministry in a post-Christendom world if we hold tight to a Christendom-shaped education model? What is needed is new wineskin for the new wine (Luke 5:33-39).

Additionally, seminaries were shaped by the strong forces of the Enlightenment, with an almost exclusive metric of evaluation that rewards the successful retention of information. Rozko and Paul also point out that graduation requirements are almost identical to secular institutions, and skill set training has been largely managerial in nature.4 We must acknowledge that most seminaries are designed to train students to become managers of church systems more than pioneers and leaders in the kingdom of God.

Thus, what can result in students is the acquisition of knowledge absent of intentional cultivation of character formation. We must ask significant questions: does our institution produce leaders who have the character of Jesus? Are they known by their love? Are students learning to live naturally supernatural lives consistent with the Sermon on the Mount? Do students’ hearts break over the brokenness they see and experience in the world? These questions are challenging, but they serve as a more consistent rubric of the way of Jesus than merely asking have they earned a degree from an accredited institution?5 Failure to address these core questions can result in graduating students with heads full of theological and doctrinal knowledge, but hearts and souls that are malformed or unformed into the way of Jesus. Therefore, what is needed for every seminary is a praxeological approach to faith formation.6 A praxeological approach in the classroom occurs when learning environments are transformed into a generative, experiential, full-bodied laboratory where kingdom imaginations are stoked, where every student’s heart, soul, mind, and strength are formed in the mission of the Shem’a of Jesus (Matthew 12:30-31), empowered by the Spirit, fueled by the Lord’s Prayer and focused on the Great Commission. Seminaries must embody the ethos of Paul’s charge to Titus: “But as for you, promote the kind of living that reflects right teaching” (Titus 2:1, NLT). But more than right thinking (orthodoxy) and right living (orthopraxy), Anglican priest Tish Harrison Warren argues that it must also be joined with right feeling (orthopathy).7 Held together, it allows students to wrestle with this whole-person oriented and robustly missional question: “How does what we learn in here [the classroom] impact what is in here [our very soul] – and out there [the world in need]?”

The ultimate purpose of the seminary is to effectively train up students to be missionary-theologians, practitioners who have the opportunity to teach others to live into Jesus’ way. For pastors and ministry leaders to effectively engage with our world, we do not need a few tweaks here and there or slight changes on the ministry dials; it will require a courageous reorientation, a radical new way of thinking and being. This, of course, impacts the institutions that train these pastors. Seminaries and pastors must own that doing more of the same will result in less of the same. This reorientation requires three primary elements: first, shifts in our assumptions about church and its intersection with culture; second, shifts in our missiological and ecclesiological approaches; and third, shifts in our institutional structures and forms.

Shifts in Our Assumptions

The first significant shift in our assumptions is, to use a sports metaphor, realizing and naming the fact that we are no longer the home team – and we are now always playing an away game. Since we are now always playing away games, it means we must change our tactics and mindset. Most significantly, this means that every seminary is charged to train students to be missionaries cleverly disguised as good neighbors, who train others to be and do the same.

Many researchers have reported the continual decrease in church attendance across almost all denominations over the past several decades in the U.S. Additionally, a recent study from the Pew Research Center released in March of 2022 reported that while more houses of worship are returning to normal operations, in-person attendance is not increasing.8 But the goal isn’t to teach students to refill the pews. As Rowland Smith writes, the church faces much bigger problems than a shrinking church roll. The more pressing issue is the “inability to live and speak the gospel into the cultural storms of our day.”9

Training students to live in a post-Christian context requires that seminaries instill a hope-filled, Christ-centered posture, not as helpless victims or resentful leaders with chips on their shoulders. Instead, students must be taught to be humble, wise servants, and cultural translators of God’s message to a world in need; we must be as shrewd as snakes and as innocent as doves. (Matthew 10:16). It means studying the lives of Daniel and his friends who lived faithfully for God in a foreign land – and committed to live with that same humble-yet-confident resolve (Daniel 3;6).10 It requires training up a generation of Issacharians, leaders who “understand the times and know what to do” (1 Chronicles 12:32) and who are able to discern the red skies (Matthew 16:1- 2). In essence, what students must be taught is semiotics, the field of study which seeks to read the signs of the times; and we must do this in order to cultivate and deepen what Leonard Sweet and Michael Beck call contextual intelligence.11

But declining church attendance should not be ignored altogether, for it has significant implications for churches and seminaries. The post-Christendom and post-pandemic realities have impacted, and will continue to impact, the size of local churches – and therefore the financial structure of each local congregation. More specifically, this will mean that many–if not most–local church pastors will be bi-vocational (or co-vocational). While some theological institutions have accommodated to meet the needs and schedules of co-vocational pastors, all seminaries must make this shift.

A second shift in our assumptions is in our approach to discipleship. We must acknowledge that our traditional approach to discipleship by and large is not working. As Dallas Willard wrote, “We must flatly say that one of the greatest contemporary barriers to meaningful spiritual formation into Christlikeness is over-confidence in the spiritual efficacy of regular church services. They are vital, but they are not enough. It is that simple.”12

As is stated often, everyone is being discipled; it is simply a matter of who or what is doing the discipling. Most churchgoers are unaware of the powerful disciple-making they are receiving from the culture (i.e., advertising, social media, entertainment, cultural assumptions in the workplace, politics, etc.). Believing that we are adequately discipling our people into the way of Jesus through just one hour during our weekend services, when the average American is exposed to 42,000 to 70,000 advertisements per week, is both naïve and inaccurate.13 We cannot live under the delusion that this will be the only way people are effectively discipled into the way of Jesus. We must have a larger, more robust kingdom imagination and clear plan to make disciples. Missiologist and practitioner Neil Cole wrote: “Ultimately, each church will be evaluated by only one thing – it’s disciples. Your church is only as good as her disciples. It does not matter how good your praise, preaching, programs or property are; if your disciples are passive, needy, consumeristic, and not radically obedient, your church is not good.”14

And it is in theological institutions where this must be taught. We need a radical shift to possess a burning passion to disciple students in the way of Jesus in every area of their lives (not just their minds). Until we realize our current approach to discipleship is anemic and irrelevant, and until we commit ourselves to a bold, new reorientation around discipleship we will not be able to effectively equip and train missionary-theologians for the post-pandemic reality.

Shifts in Our Approach

Based on these shifts in our assumptions, this should translate into several specific shifts in our approach to ministry, leadership and training. I propose four significant shifts.

Shift #1: We must cultivate a capacity for resilience and innovation in students. We now live in a VUCA world (an acronym which stands for Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguous).15 While resilience and innovation have become cultural buzzwords of late, they are needed in this season of such significant change. Sadly, resilience and innovation are not often thought of in theological education – but they should be. Christian theology is a theology of resilience. Death and resurrection is as resilient a message as has ever been proclaimed!16 And while faculty may realize the life-death-resurrection story is the gospel story as resilience, most often we fail to translate that story into a coherent and compelling framework of a theology of resilience explicitly for students.

The same could be said of innovation. Many Christian leaders and pastors are leery of innovation, as they fear it may steer away from orthodoxy. At the other end of the spectrum, many church leaders embrace innovation as the only way left to make the gospel relevant and compelling to an unbelieving world. And thus, their church services resemble the Christian version of a Coldplay concert followed by a TED Talk.17 And yet, we see missional innovation happen all throughout the book of Acts and in Paul’s missionary journeys. We read of the early church joining with God as the Spirit was doing new things. We see Paul’s innovations in his various methods, expressions, and context depending upon his audience – the same Good News but communicated in vastly different ways.

The culture of many – if not most – theological institutions is to preserve tradition rather than to spur on innovation. It is important to note that tradition is not inherently bad. We must, however, discern the important difference between tradition and traditionalism. As theologian Jaroslav Pelikan wrote, tradition is the living faith of the dead, whereas traditionalism is the dead faith of the living.18 (Or, in common parlance, it is peer pressure from dead people.) We must be able to deftly communicate the significant value of our past, while also fanning into flame the crucial need for innovation for the present and the future.

Therefore, we must always be looking for ways to pull students into the future, not merely train them for the past.19 Theological institutions must not approach the future with fear or an unhealthy over-emphasis of the past; doing so runs the risk of undervaluing how leadership and ministry can take shape in the future. Again, new wineskins for new wine.

Which leads to Shift #2: Pastors and kingdom leaders must learn to be culturally bilingual – and then, in turn, must teach their congregations to do the same. Theological institutions have done an adequate job of teaching students to exegete the Scriptures. But for the most part, institutions have failed to adequately teach students to exegete their audience. We have not taught students to read their context effectively, nor have we given them a framework of mental models, questions, and practices to utilize in listening well to the people to whom they are called to embody the gospel. Put differently, many students know how to translate the Bible in its original languages. But we must train students to translate the Bible into the “heart languages” of everyday people.

Shift #3: We must teach kingdom leaders to make self-care and soul care a higher priority. Ministry is a high-burnout profession. Sadly, most of the current pastoral imagination and frameworks of ministry “success” given to students in theological institutions often contribute to – and dare I say, at times even encourage – burnout. Too many current pastors and ministry leaders believe self-care and soul care are optional because they are too busy trying to manage and run a “successful” church. If we are to reverse the tidal wave of burnout and mental health issues hitting pastors and ministry leaders today, we will need to see self-care and soul care not as incidental add-ons to curricula, but at the very core of what seminaries and theological institutions care about (John 10:10).20 It is the role of the seminary to teach, model, and advocate this from the first day of class until graduation day. It is the integration of the with-God life that must become front and center.

Encouragingly, Christian spiritual formation and the priority of soul-shaping formational practices are growing in emphasis the past few decades through organizations like Renovaré, and resources from various Christian publishing houses. This is happening at the institutional level as well, at places like Fuller Seminary, Denver Seminary, and Friends University. And yet, as a whole, we are still far from where it must be.

This leads to Shift #4: Discipling and teaching must happen more than just from the neck up. As stated earlier, traditional theological education has placed a disproportionate emphasis on the mind. The formation of the mind is crucial, yet incomplete. Equipping and training ministry leaders effectively require that we teach on the importance of the cultivation and growth of emotional intelligence in the life of the student. Fortunately, awareness and attention to this important area has grown in the past few decades, most notably through the pioneering work of Peter Scazzerro.22

Part 2: The Way Forward

How shall seminaries respond then to these realities, and what will be required of seminaries of the future? And how shall we prepare students now for the reality of the year 2042 – and beyond? In light of the VUCA reality in which we now live, I propose that the strategic approach moving forward is not all that “innovative” (at least not in the traditional sense of the word). This is a time for institutions to spend less time, money, and energy pressing into new, cutting-edge, innovative ways and instead, to press into a faithful return to the ways of old. What is required is a vintage mindset. To look forward, we must look to our past – not in a sentimental manner which looks to the 1950s, but back much further: to the early church. We also must refrain from perpetuating ministry and leadership models based on celebrity, platform, or influence. As Scott Rodin wrote, “Godly leadership is a call to a lifestyle of an ever-decreasing thirst for authority, power, and influence.”23 We must return to the person, posture, and way of Jesus as our model for leadership.24 The following is an attempt to bring specific and practical recommendations for what seminaries – and even specifically, what Missio Seminary – can do to better prepare ministry leaders for the future.

Shifts of Our Assumptions

Based on this, there is a significant shift of assumptions that institutions must make to bring change to the classroom, which is worth touching on again. Institutions must realize an away game mentality impacts how students are taught and trained. Because the majority of pastors will be bi-vocational in the future, seminaries must grapple with the reality that the previous economic model of church will not be sustainable in the future. True, a handful of large churches will be afforded the privilege of having full-time paid staff. But the vast majority of churches must be prepared for different economic and financial models for the local church. In doing so, seminaries must talk about and help students address several dynamics in this reality. This will require faculty to teach students to assume that bi-vocational church leadership will be the ministry default position.

If affordability is not addressed strategically (and soon), institutions will run the risk of setting students – and their own institutions – up for significant financial, vocational, and personal setbacks for years to come. Fortunately, there are a few strategic models for theological education that address these limitations. For example, Greg Henson, in partnership with Sioux Falls Seminary, has launched a creative theological educational initiative called Kairos University, which is a fully customized theological education model fitting to each student’s unique context and realities. Additionally, it provides theological education at an affordable cost.25 In order to lessen the financial burden, Kairos University offers a unique monthly subscription pricing. My sincere hope and prayer is that more theological institutions would create and offer strategic, contextual, and affordable offerings that address the realities of our changing world.

Due to the bi-vocational reality, seminaries can no longer assume all or most of their students can or will be full-time students for three or four years. The academic load, frequency of classes, length of courses, and class times offered in a given semester must match the reality and lifestyle of bi-vocational pastors.

Shifts in Our Approaches to Theological Education

If there are shifts in assumptions, they must impact our approach. The first shift in approach is in providing a fully-embodied, robust praxis-oriented education. At face value, few seminaries would disagree with this statement. However, taking a closer look under the hood, we may find this is not often the case. There must be a change of orientation and values. Most seminaries graduate students who have sufficiently collected the dots. But seminaries must change the scorecard to ensure that students can sufficiently connect the dots.

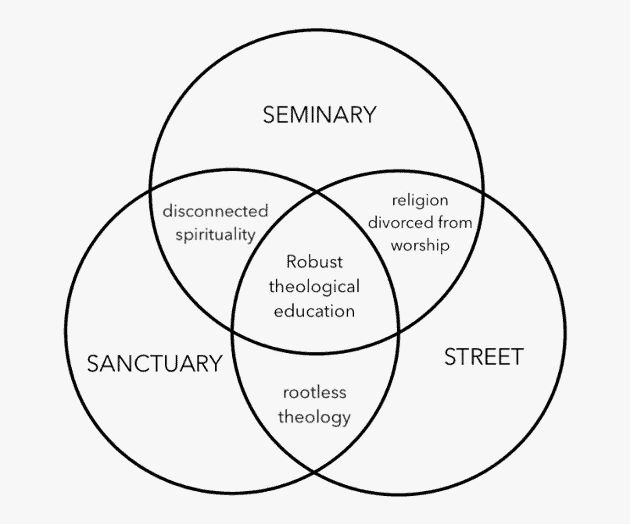

One may ask, “What are those dots?” A clearer understanding would be a three-set Venn diagram:

The objective is for students to embody all three elements: seminary education (that is, formal theological training), a connection to the sanctuary (worship – both corporate and personal – which involves inner transformation of character in becoming like Jesus), and also a connection to the street (kingdom engagement and participation in a particular proximal location).

If students embody the seminary and the sanctuary, but not the street, they will live out a disconnected or disembodied spirituality. This is what Australian missiologist Michael Frost called an excarnational reality.26 If students receive a strong seminary education in the classroom, and are engaged in the street, but disconnected from the sanctuary, it will become a religion divorced from worship. Sadly, several of my students when asked to tell me about their local church involvement have answered, “I am not connected to any local church.” This concerns and grieves me deeply. If students are connected to the sanctuary and the street, but not to the seminary, it can lead to ill-equipped and rootless leaders who are not grounded in the proper ministry assumptions and presuppositions. However, when students’ formation includes all three, they receive a robust theological education which enables them to embrace and embody a congruent, integrated, incarnational ministry presence.

The second shift of approach is introducing students to new forms, topics and elements in their educational journey. More specifically, in each course students should be exposed to four significant elements:

Element #1: practitioners who are clearly living out the gospel message in a particular context outside of the classroom. This could be in the form of in-the-field faculty, guest presenters, videos, interviews, etc. Furthermore, students must learn to think like church planters with the mindset of missionaries sent to a foreign land. Every theological institution should consider requiring a course on church planting, regardless if students sense a call to plant a church or not, in order to teach them how to think like a church planter.27

Element #2: students should be exposed frequently to incarnational stories of local churches who are living into God’s mission in Monday-through-Saturday gospel expressions. Every course should include kingdom stories of mission, redemption, reconciliation, and renewal, to hear of real examples where the gospel message is actually changing lives.

Element #3: specific tools and practical skills needed in order to be resilient and healthy missionary-practitioners. Ministry is difficult and will only become more difficult. Therefore, we must teach students what resilience is, why it is crucial today, how to cultivate a growing capacity for resilience and innovation, and to expose students to other kingdom leaders who have exhibited resilience in their lives and ministries.

And element #4: We must also teach directly on a theology of resilience which we see throughout the Scriptures – and explore biblical characters such as Abraham, Joseph, Esther, Shiphrah and Puah, Jeremiah, Ruth, Job, Mary, Paul, among many others.

The third shift of approach must be, as stated above, a higher priority of self-care and soul care. When I ask students how I can pray for them, they often tell me they have little to no margin – no time for friendships, hobbies, silence, life-giving activities, or time to just “be.” Many are rushed, stressed, distracted, overwhelmed, and sleep-deprived, and feel spiritually dry. The average seminary education, while solid in many ways, is not often purposefully designed to encourage the nurturing of students’ souls. Soul-forming practices such as keeping-sabbath, silence, stillness, and solitude are not frequently encouraged, nor is teaching about boundaries with families, or making room for key life-giving relationships – but they must.

And a fourth shift – as was touched upon earlier – is to ensure the centrality of discipleship evidenced in the curriculum. Of course, all seminaries would agree discipleship is a priority. And yet, the course requirements and selection do not often reflect the central priority of discipleship in its curriculum. Much could be said on this, but each seminary must wrestle with this crucial question: what is our plan in forming students into passionate, committed, obedient, joyful followers of Jesus – and how would we know if our plan is working? If seminaries are to make a true difference in North American culture, we must be 2 Timothy 2:2 greenhouses. This involves required courses on discipleship and disciple-making. But it also requires the institution being held accountable that each and every course can naturally and easily tie into furthering the Great Commission.

Specific Recommendations

All seminaries should seriously consider four specific requirements for graduation:

(1) That students are competent in knowing how to disciple others and have discipled at least one other person during their seminary experience – and that disciple knows how to disciple others (2 Timothy 2:2; Matthew 28:18-20).

(2) That students do not merely know about God, but that they have encountered God – and can give testimony to what God has done in them while enrolled. They can attest that they have heard the voice of God and have responded appropriately (John 15:1- 8).

(3) That students have a robust understanding of – and a personal, experiential relationship with – the Holy Spirit, showing signs of the Spirit’s clear involvement in their lives.

(4) That students grasp that healing plays a significant part in the Grand Story of God’s mission, and have experienced some form or forms of personal healing (which could be in a variety of ways), and have been given tools to know how to offer healing to others in the name of Jesus.28 This assists them in their own soul care and self-care (Matthew 11:28-30).

Beyond graduation requirements, I propose five practical changes of structure and form.

First, every seminary must expose students to new, fresh, and emerging forms of church. In the pandemic, we witnessed churches live out innovative ways to serve their neighbors in the name of Jesus. This was exciting and inspiring to see. And yet, we are still, in my estimation, one to two decades (maybe more) behind where should we with innovative forms of church.

Over the years, countless pastors have uttered this haunting line: “Seminary never trained me for what I’m doing in ministry.” To expose students to these new forms of worship we must first start by addressing foundational questions: What is church? What are the essentials of a gathered expression of the Body of Christ? Is it possible to “do church” and disciple people entirely online? Where is God at work and on the move? What are current global church planting movements that exist today and what can we learn from our global sisters and brothers? And, what might God be stirring up in my ZIP code? The goal is to increase the bandwidth of one’s understanding of the church in her various forms. Topics could include studying megachurches, micro-churches and house church movements, church planting, liturgical churches, churches with a strong charismatic emphasis, online church, the underground church movement in hostile regions of the world, and learning about organizations such as Fresh Expressions U.S.

Second, seminaries must teach on prayer, and create spaces, practices, and rhythms for prayer to become the lifeblood of the institution. What institution wouldn’t say prayer is important? Yet sadly, there are a scant few kingdom leaders who have received formal training in prayer and intercession. Additionally, seminaries often make the grave error in assuming pastors know how to pray. I will say this as clearly as I can: most pastors do not. If we fail to train kingdom leaders in how to pray – to listen to God, to sit in silence and solitude, to wait on the Lord – we are failing to adequately equip them for fruitful kingdom ministry (John 15:5). I strongly believe that a significant part of the seminary experience is for students to learn how to pray – and to be prayed for by faculty and administration. Not only have many seminaries failed to teach students to pray, they have not often created spaces, practices, and rhythms to encourage it.

At minimum, each theological education institution should require a praxis-oriented course for students on the topic of prayer. Not simply a course on what prayer is in an academic sense, but an experiential course on practicing prayer, exposing students to different forms, expressions, and traditions of prayer, helping students identify their heart language (or “prayer personality”), and requiring them to develop a prayer plan (including creating a prayer team that will intercede for them throughout their seminary experience). Is this more time, effort, work, and energy required by the school and the student? Yes. But I must ask: what is of more importance than prayer in our seminary education?

Third, we must allow space to directly address culturally pressing issues that Christians (and all people in our culture) are wrestling with. We must teach the biblical truths that undergird the complex issues at hand, while also directly addressing these topics with nuance and thoughtfulness (1 Peter 3:14-15). These issues include how to live faithfully in the post-truth era, the dangerous polarities being driven by social media, the rising environmental crisis, racial issues, confusion of sexual identities, poverty, the role of technology and artificial intelligence, global economics and justice, and the rise of secularism and how to effectively engage with the “Nones,” now a reported one-third of the U.S. identifying as religiously unaffiliated and growing.

Addressing such issues opens up the potential of encountering several significant and dangerous political landmines for any institution (which certainly makes the hairs on the backs of the necks of all administrators stand up!). And yet, while these hot-button issues seem dangerous in academic settings, we must remember that these are real issues churches and church leaders are dealing with – and will continue to deal with even more in the future. If we do not address them directly, and help kingdom leaders think through them with the gospel lens, then who will? If the goal of the seminary is institutional protection, then by all means, stay away from these issues! But if the driving purpose of the seminary is to equip students to join with God’s mission and teach them how to invite others to do the same, then we must address these issues directly – and with a posture marked by humility, conviction, sensitivity, awareness, and biblical truth.

Fourth, seminaries must look to establish creative partnerships with other leaders, organizations and potentially other schools – for effective training. We need more creative, courageous partnerships in order to be effective and fruitful in the days ahead. Many pastors in a changing cultural dynamic have confided in me saying, “I don’t have any marketable skills outside of ministry. If I ever left ministry, I would have very few options.” If bi-vocational ministry will become more of the norm, the onus is on seminaries to look for ways to creatively supplement and complement pastors’ educations with other skills that are not primarily ministry-related. These could include skills such as organizational management, marketing, finance, business, etc. One significant example is Praxis Labs, based in New York City (where one of its managing partners is kingdom leader Andy Crouch). Praxis Labs describes themselves as “a creative engine for redemptive entrepreneurship, supporting founders, funders, and innovators motivated by their faith to love their neighbors and renew culture.” And there are many others.

It is important to note: seminaries do not need to be the primary provider of these additional skills and courses, but should actively look to link arms to create synergistic and kingdom-oriented partnerships, and incentivize students to learn in new and adaptive ways. Can credit hours be offered to seminary students who take a non-profit management course from a neighboring institution? Can internship opportunities be created for students to partner with businesses and organizations, in addition to local churches or para-church organizations?

Fifth, and last, theological education institutions must look in the mirror and ask several direct questions. These are uncomfortable and will require a great deal of courage and vulnerability, yet they should not be ignored. These questions include:

- How much of what we do is about institutional preservation rather than equipping students to serve the world in the name of Jesus?

- Do we have the right administration and faculty – those who don’t just teach and lead well, but who also live effectively and faithfully as missionary-practitioners?

- Are the prayer lives of our faculty worthy of being emulated by our students?

- Are all of our courses in our curriculum – both required and elective – preparing students for the realities of the world and consistent with the values of the kingdom?

- If more pastors will be bi-vocational, what percentage of our faculty should be full-time? Might we consider increasing the percentage of bi-vocational kingdom practitioners?

- Is our institution’s financial model consistent with a world that will value full-time vocational ministry less and less, and does it set our students up for financial freedom when they graduate?

Conclusion

The global pandemic has been called the Great Disruptor, but as Roland Smith points out, Jesus himself was the Great Disruptor, “the One who often challenges our expectations, conventions, and status quo.”29 Theological education institutions are charged with teaching students to follow the Great Disruptor. This also means our own expectations, conventions, and status quo will be disrupted as well.

The vision for the hope-filled future of theological education institutions is less about emphasizing new, creative innovative ideas; instead, it is more of a call to our roots. Therefore, this will mean seminaries will need to engage in a significant amount of unlearning and relearning, for this will be the truest and best opportunity for innovation in the days ahead. This crucible moment in the history of the church and seminaries – in the best sense of the word – to practice metanoia – to rethink our ways and change our thinking. Theologian Hans Kung wrote: “The Church is essentially en route, on a journey, a pilgrimage. A church which pitches its tents without constantly looking out for new horizons, which does not continually strike camp, is being untrue to its calling. We must play down our longing for certainty, accept what is risky, and live by improvisation and experiment.”30

The same could be said for theological institutions. As Jesus taught, each teacher is to bring out old and new things from the storehouse (Matthew 13:52). But what may seem counterintuitive, striking camp for the Church, and thus for seminaries – will require a resolute commitment to return to the roots of our Christian faith.31 I hope this paper has served to affirm the importance of seminaries, while also underscoring the urgent call that seminaries must change by unlearning and relearning. In a post-pandemic and increasingly post-Christian context, change is not an option; it is absolutely required.

This is an exciting and significant moment for seminaries, but it will also require a significant amount of sacrifice and intestinal fortitude. In these uncertain times, we have every reason to maintain a posture of hopeful expectation – if we choose to act in faith. Will we merely discuss innovation in theological education, in formal and informal settings (including this colloquium)? Or will we have the faith to listen to the Spirit and courageously press into the Great Disruptor to lead us? Will we steward this kairos moment or will we choose to stick with what we have always done? We are members of the ekklesia – “the called out ones.” Do we hear Jesus calling out to us in this moment? And if so, will we choose to follow His voice?

Notes

1 For more on the concept of orientation in the Psalms, see Brueggeman’s From Whom No Secrets are Hid: Introducing the Psalms (Westminster: John Knox Press, 2014).

2 David Bosch, Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission (Maryknoll: Orbis Books, 1991), 49.

3 See JR Rozko and Doug Paul’s whitepaper, “The Missiological Future of Theological Education: A Whitepaper” (A Joint Venture of #DM and The Order of Mission), page 3.

4 Rozko and Paul, 7.

5 I’m thankful to Rozko and Paul for supplying several of these questions in their whitepaper, “The Missiological Future of Theological Education.”

6 This word is attributed to Rozko and Paul.

7 Tish Harrison Warren, “Faith Is More Than Feeling, But Not Less,” Christianity Today, March 21, 2022, https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2022/april/tish-harrison-warren-faith-orthodoxy-orthopathy-discipled.html.

8 Justin Nortey, “More houses of worship are returning to normal operations, but in-person attendance is unchanged since fall,” Pew Research Center, March 22, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/03/22/more- houses-of-worship-are-returning-to-normal-operations-but-in-person-attendance-is-unchanged-since-fall.

9 Rowland Smith, Red Skies: 10 Essential Conversations Exploring the Future as the Church (Cody: 100 Movements, 2022), xx.

10 I believe the book of Daniel must become a more prominent instructive tool for how the North American church can possess an exile mindset in order to effectively engage in our current culture.

11 See Leonard Sweet and Michael Beck’s book Contextual Intelligence: Unlocking the Ancient Secret to Mission on the Front Lines (Oviedo: HigherLife Publishing, 2020).

12 Dallas Willard, Renovation of the Heart: Putting On the Character of Christ (Colorado Springs: NavPress, 2002), 249-250.

13 Sam Carr, “How Many Ads Do We See A Day?,” Lunio (blog), February 15, 2021, https://ppcprotect.com/blog/strategy/how-many-ads-do-we-see-a-day/.

14 Neil Cole, Ordinary Hero: Becoming a Disciple Who Makes A Difference (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2011), 185.

15 The term VUCA was first introduced at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, PA. Judith Hicks Stiehm and Nicholas W. Townsend, The U.S. Army War College: Military Education in a Democracy (Temple University Press, 2022), 6.

16 We do not have time or space in this paper to articulate the many expressions of resilience in Christian and biblical theology. This is deserving of an entire paper in itself.

17 I first heard this phrase used by David French on Good Faith, the podcast he co-hosts with Curtis Chang.

18 Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, Vol. 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600) (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), 9.

19 Tod Bolsinger has written perceptively on this crucial need to rethink how we train kingdom leaders toward a preparation for an uncertain future in his book Canoeing the Mountains (Downers Grove: IVP, 2018).

20 The rendering of Matthew 11:28-30 in The Message is a beautiful example of this: “Are you tired? Worn out? Burned out on religion? Come to me. Get away with me and you’ll recover your life. I’ll show you how to take a real rest. Walk with me and work with me—watch how I do it. Learn the unforced rhythms of grace. I won’t lay anything heavy or ill-fitting on you. Keep company with me and you’ll learn to live freely and lightly.”

21 Fuller Seminary has now blended their theology and psychology/counseling departments in order to address this reality. Friends University now offers a robust cohort-based Masters of Spiritual Formation program in order to equip students to live lives of congruence of academic excellence and soul formation. Denver Seminary has developed a robust mentoring program component for their students.

22 See more of Scazzerro’s work at www.emotionallyhealthy.org.

23R. Scott Rodin, “Becoming a Leader of No Reputation,” Journal of Religious Leadership vol. 1, no. 2 (Fall 2022): 105-119.

24 See Henri Nouwen’s In the Name of Jesus: Reflections on Christian Leadership (New York: Crossroad, 1993) for a robust framework of Christian servant leadership.

25 For more information on Kairos University, see their website at www.kairos.edu.

26 See Michael Frost’s Incarnate: The Body of Christ in an Age of Disengagement (Downders Grove: IVP Books, 2014), 9.

27 Part of the curriculum must include teaching students to ask great questions for the advancement of the kingdom by studying Jesus’ approach to questions. For further thoughts, see my dissertation, “The Development and Testing of a Curriculum for Inquiry-Based Leadership in the Ecclesia Network for the Advancement of God’s Mission,” chapters 2 and 3 (DMin diss., Missio Seminary, 2019).

28 For more on this concept of joining God’s mission by receiving and extending healing in the name of Jesus see my book, A Time To Heal: Offering Hope to a Wounded World in the Name of Jesus (Richmond: Fresh Expressions U.S., 2021).

29 For more information on Fresh Expressions U.S. see www.freshexpressionsus.org.

30 Hans Kung, The Church (New York: Continuum Press, 1968), 130-131.

31 For more on this return to the past and the faithful way forward, see Alan Hirsch’s The Forgotten Ways: Reactivating Apostolic Movements (Ada: Brazos Press, 2016).